I am puzzled by the number of references to what AI “is” and what it “cannot do” when in fact the new AI is less than ten years old and is moving so fast that references to it in the present tense are dated almost before they are uttered. The statements that AI doesn’t know what it’s talking about or is not enjoying itself are trivial if they refer to the present and undefended if they refer to the medium-range future—say 30 years. —Daniel Kahneman

From left: W. Daniel Hillis, Neil Gershenfeld, Frank Wilczek, David Chalmers, Robert Axelrod, Tom Griffiths, Caroline Jones, Peter Galison, Alison Gopnik, John Brockman, George Dyson, Freeman Dyson, Seth Lloyd, Rod Brooks, Stephen Wolfram, Ian McEwan. In absentia: Andy Clark, George M. Church, Daniel Kahneman, Alex "Sandy" Pentland, Venki Ramakrishnan (Click to expand photo)

From left: W. Daniel Hillis, Neil Gershenfeld, Frank Wilczek, David Chalmers, Robert Axelrod, Tom Griffiths, Caroline Jones, Peter Galison, Alison Gopnik, John Brockman, George Dyson, Freeman Dyson, Seth Lloyd, Rod Brooks, Stephen Wolfram, Ian McEwan. In absentia: Andy Clark, George M. Church, Daniel Kahneman, Alex "Sandy" Pentland, Venki Ramakrishnan (Click to expand photo)

INTRODUCTION

by Venki Ramakrishnan

The field of machine learning and AI is changing at such a rapid pace that we cannot foresee what new technical breakthroughs lie ahead, where the technology will lead us or the ways in which it will completely transform society. So it is appropriate to take a regular look at the landscape to see where we are, what lies ahead, where we should be going and, just as importantly, what we should be avoiding as a society. We want to bring a mix of people with deep expertise in the technology as well as broad thinkers from a variety of disciplines to make regular critical assessments of the state and future of AI.

—Venki Ramakrishnan, President of the Royal Society and Nobel Laureate in Chemistry, 2009, is Group Leader & Former Deputy Director, MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology; Author, Gene Machine: The Race to Decipher the Secrets of the Ribosome.

I would like to set aside the technological constraints in order to imagine how an embodied artificial consciousness might negotiate the open system of human ethics—not how people think they should behave, but how they do behave. For example, we may think the rule of law is preferable to revenge, but matters get blurred when the cause is just and we love the one who exacts the revenge.

IAN MCEWAN is a novelist whose works have earned him worldwide critical acclaim. He is the recipient of the Man Booker Prize for Amsterdam (1998), the National Book Critics' Circle Fiction Award, and the Los Angeles Times Prize for Fiction for Atonement (2003). His most recent novel is Machines Like Me. Ian McEwan's Edge Bio Page

RODNEY BROOKS

The Cul-de-Sac of the Computational Metaphor

Have we gotten into a cul-de-sac in trying to understand animals as machines from the combination of digital thinking and the crack cocaine of computation uber alles that Moore's law has provided us? What revised models of brains might we be looking at to provide new ways of thinking and studying the brain and human behavior? Did the Macy Conferences get it right? Is it time for a reboot?

RODNEY BROOKS is Panasonic Professor of Robotics, emeritus, MIT; former director of the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and the MIT Computer Science & Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL); founder, chairman, and CTO of Rethink Robotics; and author of Flesh and Machines. Rodney Brooks's Edge Bio Page

STEPHEN WOLFRAM

Mining the Computational Universe

I've spent several decades creating a computational language that aims to give a precise symbolic representation for computational thinking, suitable for use by both humans and machines. I'm interested in figuring out what can happen when a substantial fraction of humans can communicate in computational language as well as human language. It's clear that the introduction of both human spoken language and human written language had important effects on the development of civilization. What will now happen (for both humans and AI) when computational language spreads?

STEPHEN WOLFRAM is a scientist, inventor, and the founder and CEO of Wolfram Research. He is the creator of the symbolic computation program Mathematica and its programming language, Wolfram Language, as well as the knowledge engine Wolfram|Alpha. He is also the author of A New Kind of Science. Stephen Wolfram's Edge Bio Page

FREEMON DYSON

The Brain Is Full of Maps

Brains use maps to process information. Information from the retina goes to several areas of the brain where the picture seen by the eye is converted into maps of various kinds. Information from sensory nerves in the skin goes to areas where the information is converted into maps of the body. The brain is full of maps. And a big part of the activity is transferring information from one map to another.

FREEMAN DYSON, emeritus professor of physics at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, has worked on nuclear reactors, solid-state physics, ferromagnetism, astrophysics, and biology, looking for problems where elegant mathematics could be usefully applied. His books include Disturbing the Universe, Weapons and Hope, Infinite in All Directions, and Maker of Patterns. Freeman Dyson's Edge Bio Page

CAROLINE A. JONES

Questioning the Cranial Paradigm

Part of the definition of intelligence is always this representation model. . . . I’m pushing this idea of distribution—homeostatic surfing on worldly engagements that the body is always not only a part of but enabled by and symbiotic on. Also, the idea of adaptation as not necessarily defined by the consciousness that we like to fetishize. Are there other forms of consciousness? Here’s where the gut-brain axis comes in. Are there forms that we describe as visceral gut feelings that are a form of human consciousness that we’re getting through this immune brain?

CAROLINE A. JONES is a professor of art history in the Department of Architecture at MIT and author, most recently, of The Global Work of Art. Caroline A. Jones's Edge Bio Page

ROBERT AXELROD

Collaboration and the Evolution of Disciplines

The questions that I’ve been interested in more recently are about collaboration and what can make it succeed, also about the evolution of disciplines themselves. The part of collaboration that is well understood is that if a team has a diversity of tools and backgrounds available to them—they come from different cultures, they come from different knowledge sets—then that allows them to search a space and come up with solutions more effectively. Diversity is very good for teamwork, but the problem is that there are clearly barriers to people from diverse backgrounds working together. That part of it is not well understood. The way people usually talk about it is that they have to learn each other’s language and each other’s terminology. So, if you talk to somebody from a different field, they’re likely to use a different word for the same concept.

ROBERT AXELROD, Walgreen Professor for the Study of Human Understanding at the University of Michigan, is best known for his interdisciplinary work on the evolution of cooperation. He is author of The Evolution of Cooperation. Robert Axelrod's Edge Bio Page

ALISON GOPNIK

A Separate Kind of Intelligence

It looks as if there’s a general relationship between the very fact of childhood and the fact of intelligence. That might be informative if one of the things that we’re trying to do is create artificial intelligences or understand artificial intelligences. In neuroscience, you see this pattern of development where you start out with this very plastic system with lots of local connection, and then you have a tipping point where that turns into a system that has fewer connections but much stronger, more long-distance connections. It isn’t just a continuous process of development. So, you start out with a system that’s very plastic but not very efficient, and that turns into a system that’s very efficient and not very plastic and flexible.

ALISON GOPNIK is a developmental psychologist at UC Berkeley. Her books include The Philosophical Baby and, most recently, The Gardener and the Carpenter: What the New Science of Child Development Tells Us About the Relationship Between Parents and Children. Alison Gopnik's Edge Bio Page

TOM GRIFFITHS

Doing More with Less

Imagine a superintelligent system with far more computational resources than us mere humans that’s trying to make inferences about what the humans who are surrounding it—which it thinks of as cute little pets—are trying to achieve so that it is then able to act in a way that is consistent with what those human beings might want. That system needs to be able to simulate what an agent with greater constraints on its cognitive resources should be doing, and it should be able to make inferences, like the fact that we’re not able to calculate the zeros of the Riemann zeta function or discover a cure for cancer. It doesn’t mean we’re not interested in those things; it’s just a consequence of the cognitive limitations that we have.

TOM GRIFFITHS is the Henry R. Luce Professor of Information, Technology, Consciousness, and Culture at Princeton University. He is co-author (with Brian Christian) of Algorithms to Live By. Tom Griffiths's Edge Bio Page

FRANK WILCZEK

Ecology of Intelligence

There’s this tremendous drive for intelligence, but there will be a long period of coexistence in which there will be an ecology of intelligence. Humans will become enhanced in different ways and relatively trivial ways with smartphones and access to the Internet, but also the integration will become more intimate as time goes on. Younger people who interact with these devices from childhood will be cyborgs from the very beginning. They will think in different ways than current adults do.

FRANK WILCZEK is the Herman Feshbach Professor of Physics at MIT, recipient of the 2004 Nobel Prize in physics, and author of A Beautiful Question: Finding Nature’s Deep Design. Frank Wilczek's Edge Bio Page

NEIL GERSHENFELD

Morphogenesis for the Design of Design

As we work on the self-reproducing assembler, and writing software that looks like hardware that respects geometry, they meet in morphogenesis. This is the thing I’m most excited about right now: the design of design. Your genome doesn’t store anywhere that you have five fingers. It stores a developmental program, and when you run it, you get five fingers. It’s one of the oldest parts of the genome. Hox genes are an example. It’s essentially the only part of the genome where the spatial order matters. It gets read off as a program, and the program never represents the physical thing it’s constructing. The morphogenes are a program that specifies morphogens that do things like climb gradients and symmetry break; it never represents the thing it’s constructing, but the morphogens then following the morphogenes give rise to you.

NEIL GERSHENFELD is the director of MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms; founder of the global fab lab network; the author of FAB; and co-author (with Alan Gershenfeld & Joel Cutcher-Gershenfeld) of Designing Reality. Neil Gershenfeld's Edge Bio Page

DAVID CHALMERS

The Language of Mind

Will every possible intelligent system somehow experience itself or model itself as having a mind? Is the language of mind going to be inevitable in an AI system that has some kind of model of itself? If you’ve just got an AI system that's modeling the world and not bringing itself into the equation, then it may need the language of mind to talk about other people if it wants to model them and model itself from the third-person perspective. If we’re working towards artificial general intelligence, it's natural to have AIs with models of themselves, particularly with introspective self-models, where they can know what’s going on in some sense from the first-person perspective.

DAVID CHALMERS is University Professor of Philosophy and Neural Science and co-director of the Center for Mind, Brain, and Consciousness at New York University. He is best known for his work on consciousness, including his formulation of the "hard problem" of consciousness. David Chalmers's Edge Bio Page

GEORGE DYSON

AI That Evolves in the Wild

I’m interested not in domesticated AI—the stuff that people are trying to sell. I'm interested in wild AI—AI that evolves in the wild. I’m a naturalist, so that’s the interesting thing to me. Thirty-four years ago there was a meeting just like this in which Stanislaw Ulam said to everybody in the room—they’re all mathematicians—"What makes you so sure that mathematical logic corresponds to the way we think?" It’s a higher-level symptom. It’s not how the brain works. All those guys knew fully well that the brain was not fundamentally logical.

GEORGE DYSON is a historian of science and technology and author of Darwin Among the Machines and Turing’s Cathedral. George Dyson's Edge Bio Page

PETER GALISON

Epistemic Virtues

I’m interested in the question of epistemic virtues, their diversity, and the epistemic fears that they’re designed to address. By epistemic I mean how we gain and secure knowledge. What I’d like to do here is talk about what we might be afraid of, where our knowledge might go astray, and what aspects of our fears about how what might misfire can be addressed by particular strategies, and then to see how that’s changed quite radically over time.

PETER GALISON is a science historian; Joseph Pellegrino University Professor and co-founder of the Black Hole Initiative at Harvard University; and author of Einstein's Clocks and Poincaré’s Maps: Empires of Time. Peter Galison's Edge Bio Page

SETH LLOYD

Communal Intelligence

We haven't talked about the socialization of intelligence very much. We talked a lot about intelligence as being individual human things, yet the thing that distinguishes humans from other animals is our possession of human language, which allows us both to think and communicate in ways that other animals don’t appear to be able to. This gives us a cooperative power as a global organism, which is causing lots of trouble. If I were another species, I’d be pretty damn pissed off right now. What makes human beings effective is not their individual intelligences, though there are many very intelligent people in this room, but their communal intelligence.

SETH LLOYD is a theoretical physicist at MIT; Nam P. Suh Professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering; external professor at the Santa Fe Institute; and author of Programming the Universe: A Quantum Computer Scientist Takes on the Cosmos. Seth Lloyd's Edge Bio Page

My interest in AI comes from a broader interest in a much more interesting question to which I have no answers (and can barely articulate the question): How do lots of simple things interacting emerge into something more complicated? Then how does that create the next system out of which that happens, and so on?

W. DANIEL HILLIS is an inventor, entrepreneur, and computer scientist, Judge Widney Professor of Engineering and Medicine at USC, and author of The Pattern on the Stone: The Simple Ideas That Make Computers Work. W. Daniel Hillis's Edge Bio Page

IN ABSENTIA…

Andy Clark

Perception itself is a kind of controlled hallucination. . . . [T]he sensory information here acts as feedback on your expectations. It allows you to often correct them and to refine them. But the heavy lifting seems to be being done by the expectations. Does that mean that perception is a controlled hallucination? I sometimes think it would be good to flip that and just think that hallucination is a kind of uncontrolled perception.

ANDY CLARK is professor of Cognitive Philosophy at the University of Sussex and author of Surfing Uncertainty: Prediction, Action, and the Embodied Mind. Andy Clark’s Edge Bio Page

George M. Church

The opportunity is not mere AI-ML, but various hybrids of inorganic-digital-von Neumann architectures with “Natural computing” (CAD of natural phenomena and/or employing semi-natural materials to compute), which benefits from our exponentially growing synthetic capabilities. Also, both of these are being hybridized with highly evolved human brains (including long-tail exceptional individuals) and our new tools for building more and more complex synthetic human brain components using genetics and in-vitro developmental biology.

GEORGE M. CHURCH is Robert Winthrop Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, Professor of Health Sciences and Technology at Harvard-MIT, and co-author (with Ed Regis) of Regenesis: How Synthetic Biology Will Reinvent Nature and Ourselves. George Church’s Edge Bio Page

Daniel Kahneman

My late teacher Yehoshua Bar-Hillel was once asked, in the 1950s, whether computers would ever understand language. He answered unhesitatingly “Never” and immediately clarified that by “Never” he meant “at least 50 years.” I am puzzled by the number of references to what AI “is” and what it “cannot do” when in fact the new AI is less than ten years old and is moving so fast that references to it in the present tense are dated almost before they are uttered. The statements that AI doesn’t know what it’s talking about or is not enjoying itself are trivial if they refer to the present and undefended if they refer to the medium-range future—say 30 years. Hype is bad, but the debunkers should remember that the AI Winter was brought about by two brilliant people proving what a one-layer Perceptron could not do. My optimistic question would be “Where will the next breakthrough in AI come from—and what will it easily do that deep learning is not good at?”

DANIEL KAHNEMAN, Nobel Laureate in Economic Sciences (2002), is Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology Emeritus at Princeton University, Professor of Psychology and Public Affairs Emeritus at the Woodrow Wilson School, and winner of the 2013 Presidential Medal of Honor. He is author of Thinking, Fast and Slow. Daniel Kahneman’s Edge Bio Page

Alex “Sandy” Pentland

For the first time in history there is fine-grained data about the behavior of everyone in entire societies, from phones, transactions, transport, etc. This data shows that people are not very different from other social species, with the exception that we have much better social learning, and so we are much better at building a common set of heuristics generally known as culture. The math of this process is very similar to a distributed version of a well-known near-optimal financial portfolio strategy, and is analogous to reinforcement learning over a space of "micro-strategies." This insight suggests a way to make humanity as a whole much smarter than we are today, something I call "HumanAI."

ALEX “SANDY” PENTLAND is Toshiba Professor and professor of media arts and sciences at MIT; director of the Human Dynamics and Connection Science labs and the Media Lab Entrepreneurship Program, and the author of Social Physics. Sandy Pentland’s Edge Bio Page

Venki Ramakrishnan

The field of machine learning and AI is changing at such a rapid pace that we cannot foresee what new technical breakthroughs lie ahead, where the technology will lead us or the ways in which it will completely transform society. So it is appropriate to take a regular look at the landscape to see where we are, what lies ahead, where we should be going and, just as importantly, what we should be avoiding as a society. We want to bring a mix of people with deep expertise in the technology as well as broad thinkers from a variety of disciplines to make regular critical assessments of the state and future of AI.

VENKI RAMAKRISHNAN, President of the Royal Society, is the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 2009, and Group Leader & Former Deputy Director, MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology. He is the author of Gene Machine: The Race to Decipher the Secrets of the Ribosome. Venki Ramakrishan’s Edge Bio Page

Front Page

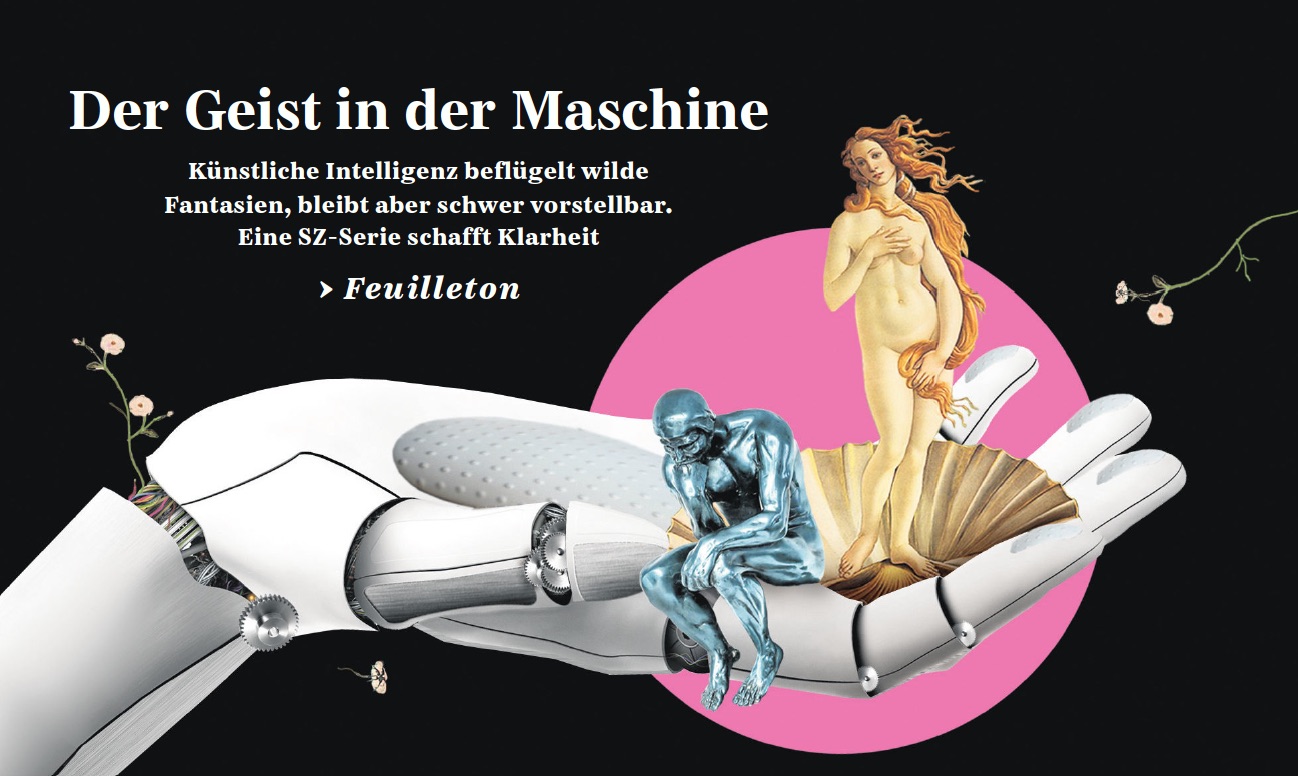

DEFGH Nr. 63, Freitag, 15. März 2019.

Collage: Stefan Dimitrov

The Ghost in the Machine

Artificial intelligence inspires wild fantasies, but remains hard to imagine. A SZ series creates clarity.

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Artificial intelligence:

A new series brings science and culture together to fathom the inexplicable

_________________________________________________

The Overdue Debate

By Andrian Kreye

Friday, March 15, 2019

_________________________________________

The Spirit In The Machine

What does artificial intelligence mean?

A series of essays seeks answers.

Part 1

_________________________________________

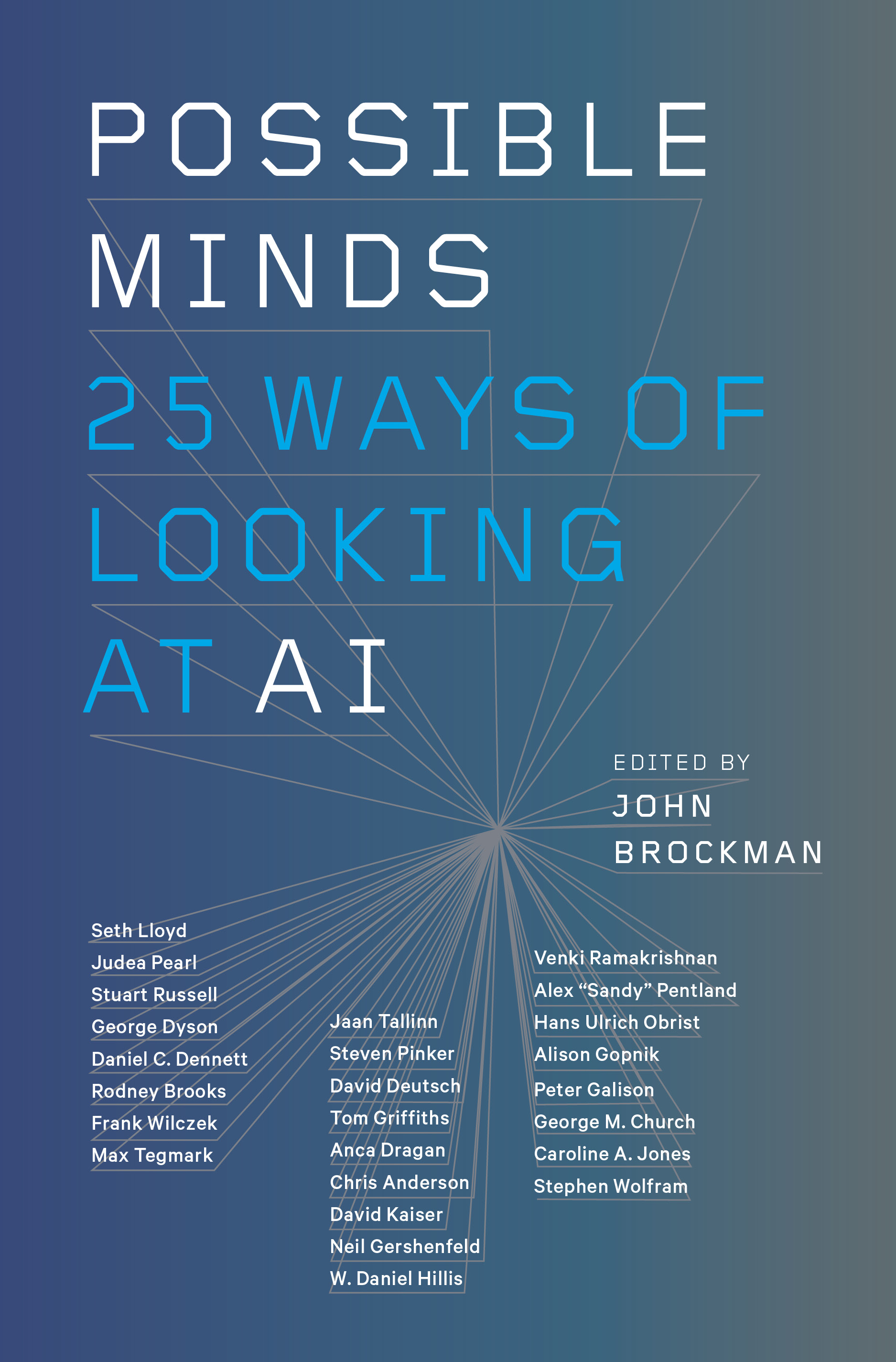

John Brockman has long called for, and practiced, the unification of the natural sciences and humanities into what he has called “the third culture”. He is the founder of the debate forum Edge.org, where scientists, writers and artists work together to ask the great questions of the present. Since 1981, his "Reality Club" has held gatherings in New York, San Francisco or London in pubs, lofts, museums and living rooms. In 1996, he migrated the debate to Edge.org on the web, which led to his Edge dinners.

Because he has a full-time career as a literary agent for science authors, as well as being the first to negotiate major deals for books by bestselling academics such as Daniel Kahneman, Richard Dawkins or Lisa Randall, his roundtable was always already very prominently cast.

One can imagine the 78-year-old today as a mixture of King Arthur and Dorothy Parker. On the one hand, he often recognizes powerful talents earlier than others, which led to the fact that he had the Google founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page, Amazon boss Jeff Bezos or the boy-wonder of Facebook as guests at his dinner parties even when they were still precocious start-up entrepreneurs. On the other hand, he has the humor and charm to keep you on your toes at such events, whether in the back room of a restaurant, at workshop weekends on his farm near New York, or on his web pages.

So it was a rare “must” in the social life of Harvard University when he recently invited a large group to an evening event in Cambridge at the Brattle Theatre, followed by a dinner at the Charles Hotel to continue the debate on artificial intelligence, which he had presented as a "Possible Minds" project last fall. Many of those who attended are celebrated as stars in scientific circles—such as the cognition researcher Steven Pinker, the robot ethicist Kate Darling, the science philosopher Max Tegmark and as an eminence price, the writer and anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson.

In the theater they delivered 5-minute Lightning talks (lectures), presenting a picture of the state of things as wide-ranging as anything currently running in the A.I. debate.

Mary Catherine Bateson began the evening with a call for the need to revive the almost forgotten science of systems theory in light of the complex networks of AI. The developmental psychologist Alison Gopnik asked that we remember that while four-year-olds are mentally immature, they’re fitter than any AI. Max Tegmark compared A.I. to a missile that requires precise control by humans.

And Stephen Wolfram was enthusiastic about the almost unlimited possibilities still beyond our understanding.

_________________________________________

John Brockman’s

Dinners are Today’s

"Roundtables"

_________________________________________

As a non-academic guest of the following dinner I realized how deeply connected the various disciplines of the humanities and sciences already are in places like Cambridge, MA. It felt like being at a great reunion, hugs and gossip included. John Brockman ruled the room like a social alchemist, taking some from the numerous groups adding them to another to spark new conversations. One could learn about the latest breakthroughs in science or about how projects like AI enhanced democratic processes neutralizing lobbyists and empowering voters, or get a sense of greater trends like programmable cells (which might have an even greater impact on history than AI, especially if you talk to a biologist).

John Brockman's most recent roundtables in artificial intelligence has resulted in an essay collection. Authors and scientists such as the geneticist George Church, Alison Gopnik, the art historian Caroline Jones, Steven Pinker and the Nobel laureate and president of the Royal Society Venki Ramakrishnan have joined the debate about artificial intelligence. The Süddeutsche Zeitung will make the essays available to the public in the coming weeks, publishing them in the Feuilleton.

We will also invite, and publish in our pages, the first reactions of German and European intellectuals, cultural figures, and natural scientists. This will be the beginning of a debate the end of which is not in sight.’

Andrian Kreye is the Feuilleton Editor of Süddeutsche Zeitung. © Süddeutsche Zeitung GmbH, Munich. Courtesy of Süddeutsche Zeitung Content.

Journalist Andrian Kreye (Süddeutsche Zeitung) wins Theodor Wolff Prize in "Topic of the Year" Category for Artificial Intelligence Series

June 26, 2019

The Spirit of Unlimited Possibilities

Cage's dinner parties were an ongoing seminar on media, communication, art, music and philosophy, driven by Cage's interest in the ideas of Wiener, Claude Shannon and Marshall McLuhan. Cage was particularly fascinated by McLuhan's idea that with the invention of electronic technologies we had externalized our central nervous system, that is, our mind, and that we had to assume that "there is only one mind that we all share. Such ideas were increasingly circulating among artists and intellectuals at the time. Many of these people were reading Wiener, and cybernetics was in the air. During one of those dinners, Cage reached into his briefcase and pulled out a copy Wiener's Cybernetics and handed it to me with the words: “This is for you." That was a key moment for everything I've done in the last 53 years.

During the festival, I received an unexpected phone call from Wiener’s colleague Arthur K. Solomon, head of Harvard’s Biophysics Department. Wiener had died the year before, and Solomon’s and Wiener’s other close colleagues at MIT and Harvard had been reading about the Expanded Cinema Festival in the New York Times and were intrigued by the connection to Wiener’s work. Solomon invited me to bring some of the artists up to Cambridge to meet with him and a group that included MIT sensory communications researcher Walter Rosenblith, Harvard applied mathematician Anthony Oettinger, and MIT engineer Harold “Doc” Edgerton, inventor of the strobe light.

New Technologies = New Perceptions

Like many other “art meets science” situations I’ve been involved in since, the two-day event was an informed failure: ships passing in the night. But I took it all on board and the event was consequential in some interesting ways—one of which came from the fact that they took us to see “the” computer. Computers were a rarity back then; at least none of us on the visit had ever seen one. We were ushered into a large space on the MIT campus, in the middle of which there was a “cold room” raised off the floor and enclosed in glass, in which technicians wearing white lab coats, scarves, and gloves were busy collating punch cards coming through an enormous machine. When I approached, the steam from my breath fogged up the window into the cold room. Wiping it off, I saw “the” computer. I fell in love.

I began to develop a theme, a mantra of sorts, that has informed my endeavors since: “new technologies = new perceptions.” Inspired by communications theorist Marshall McLuhan, architect-designer Buckminster Fuller, futurist John McHale, and cultural anthropologists Edward T. “Ned” Hall and Edmund Carpenter, I started reading avidly in the fields of information theory, cybernetics, and systems theory. McLuhan himself suggested I read Warren Weaver and Claude Shannon’s 1949 paper “Recent Contributions to the Mathematical Theory of Communication,” which begins: “The word communication will be used here in a very broad sense to include all of the procedures by which one mind may affect another. This, of course, involves not only written and oral speech, but also music, the pictorial arts, the theater, the ballet, and in fact all human behavior.”

Reality is a man-made process. The images we make of ourselves and our world are in part models rooted in the knowledge of the technologies we create. Although many of us weren't ready yet, after only a few years we looked at our brain as a computer. And when we connected computers to the Internet, we realized that our brain is not a computer, but a network of computers.

Basic text of the digital debate: Norbert Wiener's Cybernetics of 1948. Photo: SZ

Two years after Cybernetics, in 1950, Norbert Wiener published The Human Use of Human Beings—a deeper story, in which he expressed his concerns about the runaway commercial exploitation and other unforeseen consequences of the new technologies of control. I didn’t read The Human Use of Human Beings until the spring of 2016, when I picked up my copy, a first edition, which was sitting in my library next to Cybernetics. What shocked me was the realization of just how prescient Wiener was in 1950 about what’s going on today. Although the first edition was a major bestseller—and, indeed, jump-started an important conversation—under pressure from his peers Wiener brought out a revised and milder edition in 1954, from which the original concluding chapter, “Voices of Rigidity,” is conspicuously absent.

Science historian George Dyson points out that in this long-forgotten first edition, Wiener predicted the possibility of a “threatening new Fascism dependent on the machine à gouverner”:

No elite escaped his criticism, from the Marxists and the Jesuits (“all of Catholicism is indeed essentially a totalitarian religion”) to the FBI (“our great merchant princes have looked upon the propaganda technique of the Russians, and have found that it is good”) and the financiers lending their support “to make American capitalism and the fifth freedom of the businessman supreme throughout the world.” Scientists. . . received the same scrutiny given the Church: “Indeed, the heads of great laboratories are very much like Bishops, with their association with the powerful in all walks of life, and the dangers they incur of the carnal sins of pride and of lust for power.”

This jeremiad did not go well for Wiener. As Dyson puts it:

These alarms were discounted at the time, not because Wiener was wrong about digital computing but because larger threats were looming as he completed his manuscript in the fall of 1949. Wiener had nothing against digital computing but was strongly opposed to nuclear weapons and refused to join those who were building digital computers to move forward on the thousand-times-more-powerful hydrogen bomb.

Since the original of The Human Use of Human Beings is now out of print, lost to us is Wiener’s cri de coeur, more relevant today than when he wrote it sixty-eight years ago: “We must cease to kiss the whip that lashes us.”

It Is Time to Challenge the Prevailing Digital AI Narrative

Among the reasons we don’t hear much about cybernetics today, two are central: First, although The Human Use of Human Beings was considered an important book in its time, it ran counter to the aspirations of many of Wiener’s colleagues, including John von Neumann and Claude Shannon, who were interested in the commercialization of the new technologies. Second, computer pioneer John McCarthy disliked Wiener and refused to use Wiener’s term “Cybernetics.” McCarthy, in turn, coined the term “artificial intelligence” and became a founding father of that field.

Cybernetics, rather than disappearing, was becoming metabolized into everything, so we no longer saw it as a separate, distinct new discipline. And there it remains, hiding in plain sight.

Now AI is everywhere. We have the Internet. We have our smartphones. The founders of the dominant companies— the companies that hold “the whip that lashes us”— have net worths of $65 billion, $90 billion, $150 billion. High- profile individuals such as Elon Musk, Nick Bostrom, Martin Rees, Eliezer Yudkowsky, and the late Stephen Hawking have issued dire warnings about AI, resulting in the ascendancy of well-funded institutes tasked with promoting “Nice AI.” But will we, as a species, be able to control a fully realized, unsupervised, self-improving AI? Wiener’s warnings and admonitions in The Human Use of Human Beings are now very real, and they need to be looked at anew by researchers at the forefront of the AI revolution.

Here is Dyson again:

Wiener became increasingly disenchanted with the “gadget worshipers” whose corporate selfishness brought “motives to automatization that go beyond a legitimate curiosity and are sinful in themselves.” He knew the danger was not machines becoming more like humans but humans being treated like machines. “The world of the future will be an ever more demanding struggle against the limitations of our intelligence,” he warned in God & Golem, Inc., published in 1964, the year of his death, “not a comfortable hammock in which we can lie down to be waited upon by our robot slaves.”

Thus, it’s time to present the ideas of a community of sophisticated thinkers who are bringing their experience and erudition to bear in challenging the prevailing digital AI narrative as they communicate their thoughts to one another. The aim is to present a mosaic of views that will help make sense out of this rapidly emerging field.

Similar to the fable of the blind man and the elephant, AI is far too big a subject to be viewed from a single angle. The "Possible Minds Project," from which the essays in this series emerged, and are also published as CT, where some of the authors of these essays were also present.

Since then, I have hosted a series of dinners and discussions in New York, London, Cambridge, and the Serpentine Marathon on Artificial Intelligence, and major public events at London City Hall, The Brattle Theatre in Cambridge, The LongNow at SF Jazz, and Pioneer Works, in Brooklyn. Among the guests were natural scientists and humanists, communication theorists, science historians, philosophers and artists, all of whom have thought very seriously about artificial intelligence throughout their professional lives. It’s time to examine the evolving AI narrative by identifying the leading members of that mainstream community along with the dissidents and presenting their counter-narratives in their own voices.

The essays that follow thus constitute a much-needed update from the field.

[Adapted from Introduction, Possible Minds: 25 of Looking at AI, edited by John Brockman (Penguin Press, 2019)]

Collage: Stefan Dimitrov

[enlarge]

A Question of Faith

By George Dyson

Monday, September 23, 2019

Collage: Stefan Dimitrov

[enlarge]

A Dream of Objectivity

By Peter Galison

Saturday, August 10, 2019

Collage: Stefan Dimitrov

[enlarge]

Once Again With Feeling

By Alex "Sandy" Pentland

Wednesday, July 24, 2019

Collage: Stefan Dimitrov

[enlarge]

Will Computers Be Our Rulers?

By Venki Ramakrishnan

Tuesday, July 16, 2019

Collage: Stefan Dimitrov

[enlarge]

The Circle is Closing

By Neil Gershenfeld

Tuesday, June 4, 2019

Collage: Stefan Dimitrov

[enlarge]

Borders of Obscure Learning

By Judea Pearl

Wednesday, May 15, 2019

Collage: Stefan Dimitrov

[enlarge]

Unpredictable Human

By Anca Dragan

Tuesday, April 23, 2019

Collage: Stefan Dimitrov

[enlarge]

Meat and Blood Machines

By W. Daniel Hillis

Wednesday, April 10, 2019

Collage: Stefan Dimitrov

[enlarge]

Beings and Tools

By Daniel C. Dennett

Monday, April 1, 2019

Collage: Stefan Dimitrov

[enlarge]

The Wisdom of Children

By Alison Gopnik

Tuesday, March 26, 2019

[Adapted from Chapter 21 - "AIs Versus Four-Year-Olds" by Alison Gopnik, from Possible Minds: 25 of Looking at AI, edited by John Brockman (Penguin Press, 2019)]

Collage: Stefan Dimitrov

[enlarge]

What Is Intelligence Anyway?

By Steven Pinker

Wednesday, March 20, 2019

(ED. NOTE: In 2015, Edge presented "A Short Course in Superforecasting" with political and social scientist Philip Tetlock. Superforecasting is back in the news this week thanks to the UK news coverage of comments by Boris Johnson's chief adviser Dominic Cummings, who urged journalists to "read Philip Tetlock's Superforecasters [sic], instead of political pundits who don't know what they're talking about.")

PHILIP E. TETLOCK, political and social scientist, is the Annenberg University Professor at the University of Pennsylvania, with appointments in Wharton, psychology and political science. He is co-leader of the Good Judgment Project, a multi-year forecasting study, author of Expert Political Judgment, co-author of Counterfactual Thought Experiments in World Politics (with Aaron Belkin), and co-author of Superforecasting: The Art & Science of Prediction (with Dan Gardner). Further reading on Edge: "How to Win at Forecasting: A Conversation with Philip Tetlock" (December 6, 2012). Philip Tetlock's Edge Bio Page.

CLASS I — Forecasting Tournaments: What We Discover When We Start Scoring Accuracy

It is as though high status pundits have learned a valuable survival skill, and that survival skill is they've mastered the art of appearing to go out on a limb without actually going out on a limb. They say dramatic things but there are vague verbiage quantifiers connected to the dramatic things. It sounds as though they're saying something very compelling and riveting. There's a scenario that's been conjured up in your mind of something either very good or very bad. It's vivid, easily imaginable.

It turns out, on close inspection they're not really saying that's going to happen. They're not specifying the conditions, or a time frame, or likelihood, so there's no way of assessing accuracy. You could say these pundits are just doing what a rational pundit would do because they know that they live in a somewhat stochastic world. They know that it's a world that frequently is going to throw off surprises at them, so to maintain their credibility with their community of co-believers they need to be vague. It's an essential survival skill. There is some considerable truth to that, and forecasting tournaments are a very different way of proceeding. Forecasting tournaments require people to attach explicit probabilities to well-defined outcomes in well-defined time frames so you can keep score.

CLASS II — Tournaments: Prying Open Closed Minds in Unnecessarily Polarized Debates

Tournaments have a scientific value. They help us test a lot of psychological hypotheses about the drivers of accuracy, they help us test statistical ideas; there are a lot of ideas we can test in tournaments. Tournaments have a value inside organizations and businesses. A more accurate probability helps to price options better on Wall Street, so they have value.

I wanted to focus more on what I see as the wider societal value of tournaments and the potential value of tournaments in depolarizing unnecessarily polarizing policy debates. In short, making us more civilized. ...

There is well-developed research literature on how to measure accuracy. There is not such well-developed research literature on how to measure the quality of questions. The quality of questions is going to be absolutely crucial if we want tournaments to be able to play a role in tipping the scales of plausibility in important debates, and if you want tournaments to play a role in incentivizing people to behave more reasonably in debates.

CLASS III — Counterfactual History: The Elusive Control Groups in Policy Debates

There's a picture of two people on slide seventy-two, one of whom is one of the most famous historians in the 20th century, E.H. Carr, and the other of whom is a famous economic historian at the University of Chicago, Robert Fogel. They could not have more different attitudes toward the importance of counterfactuals in history. For E.H. Carr, counterfactuals were a pestilence, they were a frivolous parlor game, a methodological rattle, a sore loser's history. It was a waste of cognitive effort to think about counterfactuals. You should think about history the way it did unfold and figure out why it had to unfold the way it did—almost a prescription for hindsight bias.

Robert Fogel, on the other hand, approached it more like a scientist. He quite correctly recognized that if you want to draw causal inferences from any historical sequence, you have to make assumptions about what would have happened if the hypothesized cause had taken on a different value. That's a counterfactual. You had this interesting tension. Many historians do still agree, in some form, with E.H. Carr. Virtually all economic historians would agree with Robert Fogel, who's one of the pivital people in economic history; he won a Nobel Prize. But there's this very interesting tension between people who are more open or less open to thinking about counterfactuals. Why that is, is something that is worth exploring.

CLASS IV — Skillful Backward and Forward Reasoning in Time: Superforecasting Requires "Counterfactualizing"

A famous economist, Albert Hirschman, had a wonderful phrase, "self-subversion." Some people, he thought, were capable of thinking in self-subverting ways. What would a self-subverting liberal or conservative say about the Cold War? A self-subverting liberal might say, "I don’t like Reagan. I don’t think he was right, but yes, there may be some truth to the counterfactual that if he hadn’t been in power and doing what he did, the Soviet Union might still be around." A self-subverting conservative might say, "I like Reagan a lot, but it’s quite possible that the Soviet Union would have disintegrated anyway because there were lots of other forces in play."

Self-subversion is an integral part of what makes superforecasting cognition work. It’s the willingness to tolerate dissonance. It’s hard to be an extremist when you engage in self-subverting counterfactual cognition. That’s the first example. The second example deals with how regular people think about fate and how superforecasters think about it, which is, they don’t. Regular people often invoke fate, "it was meant to be," as an explanation for things.

CLASS V — Condensing it All Into Four Big Problems and a Killer App Solution

The beauty of forecasting tournaments is that they’re pure accuracy games that impose an unusual monastic discipline on how people go about making probability estimates of the possible consequences of policy options. It’s a way of reducing escape clauses for the debaters, as well as reducing motivated reasoning room for the audience.

Tournaments, if they’re given a real shot, have a potential to raise the quality of debates by incentivizing competition to be more accurate and reducing functionalist blurring that makes it so difficult to figure out who is closer to the truth.

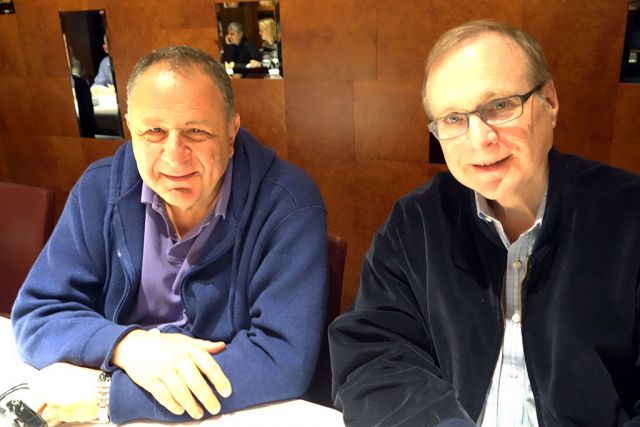

In the circle of clairvoyants: At a vineyard north of San Francisco, Philip Tetlock of the University of Pennsylvania (left) presented his findings. Initially skeptical was Nobel Laureate Kahneman (third from left). Photo: John Brockman / edge.org

ATTENDEES:

Robert Axelrod, Political Scientist; Walgreen Professor for the Study of Human Understanding, U. Michigan; Author, The Evolution of Cooperation; Member, National Academy of Sciences; Recipient, the National Medal of Science; Stewart Brand, Founder, The Whole Earth Catalog; Co-Founder, The Well; Co-Founder, The Long Now Foundation; Author, Whole Earth Discipline; John Brockman, Editor, Edge; Author, The Third Culture; Rodney Brooks, Panasonic Professor of Robotics (emeritus), MIT; Founder, Chmn/CTO, Rethink Robotics; Author, Flesh and Machines; Brian Christian, Philosopher, Computer Scientist, Poet; Author, The Most Human Human; Wael Ghonim, Pro-democracy leader of the Tarir Square demonstrations in Egypt; Anonymous administrator of the Facebook page, "We are all Khaled Saeed"; W. Daniel Hillis, Physicist; Computer Scientist; Chairman, Applied Minds; Author, The Pattern on the Stone; Jennifer Jacquet, Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies, NYU; Author, Is Shame Necessary?; Daniel Kahneman, Professor Emeritus of Psychology, Princeton; Author, Thinking, Fast and Slow; Winner of the 2013 Presidential Medal of Freedom; Recipient of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences; Salar Kamangar, Senior Vice President, Google; Fmr head of YouTube; Dean Kamen, Inventor and Entrepreneur, DEKA Research; Andrian Kreye, Feuilleton Editor, Sueddeutsche Zeitung, Munich; Peter Lee, Corp. VP, Microsoft Research; Former Founder / Director, DARPA's technology office; Former Head, Carnegie Mellon Computer Science Department & CMU's Vice Provost for Research; Margaret Levi, Political Scientist, Director, Center For Advanced Study in Behavioral Sciences (CASBS), Stanford University; Barbara Mellers, Psychologist; George Heyman University Professor at UPennsylvania; Past President, Society of Judgment and Decision Making; Ludwig Siegele, Technology Editor, The Economist; Rory Sutherland, Executive Creative Director and Vice-Chairman, OgilvyOne London; Vice-Chairman, Ogilvy & Mather UK; Columnist, The Spectator; Philip Tetlock, Political and Social Scientist; Annenberg University Professor at UPenn; Author, Expert Political Judgment; and (with Dan Gardner) Superforecasting (forthcoming); Anne Treisman, James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor Emeritus of Psychology at Princeton; Recipient, National Medal of Science; D.A.Wallach, Recording Artist; Songwriter; Artist in Residence, Spotify; Hi-Tech Investor

"To accomplish the extraordinary, you must seek extraordinary people."

A new generation of artists, writing genomes as fluently as Blake and Byron wrote verses, might create an abundance of new flowers and fruit and trees and birds to enrich the ecology of our planet. Most of these artists would be amateurs, but they would be in close touch with science, like the poets of the earlier Age of Wonder. The new Age of Wonder might bring together wealthy entrepreneurs ... and a worldwide community of gardeners and farmers and breeders, working together to make the planet beautiful as well as fertile, hospitable to hummingbirds as well as to humans. —Freeman Dyson

In his 2009 talk at the Bristol Festival of Ideas, Freeman Dyson pointed out that we are entering a new Age of Wonder, which is dominated by computational biology. The leaders of the new Age of Wonder, Dyson noted, include "biology wizards" Kary Mullis, Craig Venter, medical engineer Dean Kamen, and "computer wizards" Larry Page, Sergey Brin, and Charles Simonyi, and John Brockman and Katinka Matson, the cofounders of Edge, the nexus of this intellectual activity.

Every year since 1999, we have hosted The Edge Annual Dinner (sometimes referred to as “The Billionaires' Dinner”). Guests have included the leading third culture intellectuals of our time, dining and conversing with the founders of Amazon, AOL, eBay, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, PayPal, Space X, Skype, and Twitter. It is a remarkable gathering of outstanding minds—the people who are rewriting our global culture.

Paul Allen, Julia Milner, Yuri Milner

Through such gatherings, its online publications, master classes, and seminars, Edge, operating under the umbrella of the non-profit 501 (c) (3) Edge Foundation, Inc., promotes interactions between the third culture intellectuals and technology pioneers of the post-industrial, digital age, the "worldwide community of gardeners and farmers and breeders" referred to by Dyson as the leaders of the "Age of Wonder”. Edge members share the boundaries of their knowledge and experience with each other and respond to challenges, comments, criticisms, and insights. The constant shifting of metaphors, the intensity with which we advance our ideas to each other—this is what intellectuals do. Edge draws attention to the larger context of intellectual life.

An indication of Edge's role in contemporary culture can be measured, in part, by its Google PageRank of "8", which places it in the same category as The Economist, Financial Times, Le Monde, La Repubblica, Science, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post. Its influence is evident from the attention paid by the global media:

"The world's smartest website … a salon for the world's finest minds." Guardian—"the fabulous Edge symposium" New York Times—"A lavish cerebral feast", Atlantic—"Not just wonderful, but plausible", Wall St. Journal "Fabulous", Independent—" Thrilling", FAZ—"The brightest minds", Vanity Fair, "The intellectual elite", Guardian—"Intellectual skyrockets of stunning brilliance", Arts & Letter Daily—"Terrific, thought provoking", Guardian— "An intellectual treasure trove, San Francisco Chronicle—"Thrilling colloquium", Telegraph—"Fantastically stimulating", BBC Radio 4—"Astounding reading", Boston Globe—"Where the age of biology began", Süddeutsche Zeitung—"Splendidly enlightened", Independent—The world’s best brains", Times— "Brilliant... a eureka moment at the edge of knowledge", Sunday Times—"Fascinating and provocative", Guardian—"Uplifting ...enthralling", Daily Mail—"Breathtaking in scope", New Scientist—"Exhilarating, hilarious, and chilling", Evening Standard—"Today's visions of science tomorrow", New York Times

Edge is different from The Invisible College (1646), The Club (1764), The Cambridge Apostles (1820), The Bloomsbury Group (1905), or The Algonquin Roundtable (1919), but it offers the same quality of intellectual adventure.

Perhaps the closest resemblance is to the early nineteenth century Lunar Society of Birmingham (1765), an informal dinner club and learned society of leading cultural figures of the new industrial age—James Watt, Joseph Priestly, Benjamin Franklin, and the two grandfathers of Charles Darwin, Erasmus Darwin and Josiah Wedgwood. The Society met each month near the full moon. They referred to themselves as "lunaticks". In a similar fashion, Edge attempts to inspire conversations exploring the themes of the post-industrial age.

In this regard, Edge is not just a group of people. I see it as the constant shifting of metaphors, the advancement of ideas, the agreement on, and the invention of, reality.

—John Brockman

Vancouver, March 18, 2015

"To arrive at the edge of the world's knowledge, seek out the most complex and sophisticated minds, put them in a room together, and have them ask each other the questions they are asking themselves."

HEADCON '14

In September a group of social scientists gathered for HEADCON '14, an Edge Conference at Eastover Farm. Speakers addressed a range of topics concerning the social (or moral, or emotional) brain: Sarah-Jayne Blakemore: "The Teenager's Sense Of Social Self"; Lawrence Ian Reed: "The Face Of Emotion"; Molly Crockett: "The Neuroscience of Moral Decision Making"; Hugo Mercier: "Toward The Seamless Integration Of The Sciences"; Jennifer Jacquet: "Shaming At Scale"; Simone Schnall: "Moral Intuitions, Replication, and the Scientific Study of Human Nature"; David Rand: "How Do You Change People's Minds About What Is Right And Wrong?"; L.A. Paul: "The Transformative Experience"; Michael McCullough: "Two Cheers For Falsification". Also participating as "kibitzers" were four speakers from HEADCON '13, the previous year's event: Fiery Cushman, Joshua Knobe, David Pizarro, and Laurie Santos.

We are now pleased to present the program in its entirety, nearly six hours of Edge Video and a downloadable PDF of the 55,000-word transcript.

[6 hours]

John Brockman, Editor

Russell Weinberger, Associate Publisher

Copyright (c) 2014 by Edge Foundation, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Please feel free to use for personal, noncommercial use (only).

_____

Related on Edge:

HeadCon '13

Edge Meetings & Seminars

Edge Master Classes

CONTENTS

Sarah-Jayne Blakemore: "The Teenager's Sense Of Social Self"

The reason why that letter is nice is because it illustrates what's important to that girl at that particular moment in her life. Less important that man landed on moon than things like what she was wearing, what clothes she was into, who she liked, who she didn't like. This is the period of life where that sense of self, and particularly sense of social self, undergoes profound transition. Just think back to when you were a teenager. It's not that before then you don't have a sense of self, of course you do. A sense of self develops very early. What happens during the teenage years is that your sense of who you are—your moral beliefs, your political beliefs, what music you're into, fashion, what social group you're into—that's what undergoes profound change.

[36.22]

SARAH-JAYNE BLAKEMORE is a Royal Society University Research Fellow and Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, University College London. Sarah-Jayne Blakemore's Edge Bio Page

Lawrence Ian Reed: "The Face Of Emotion"

What can we tell from the face? There’s some mixed data, but data out that there’s a pretty strong coherence between what is felt and what’s expressed on the face. Happiness, sadness, disgust, contempt, fear, anger, all have prototypic or characteristic facial expressions. In addition to that, you can tell whether two emotions are blended together. You can tell the difference between surprise and happiness, and surprise and anger, or surprise and sadness. You can also tell the strength of an emotion. There seems to be a relationship between the strength of the emotion and the strength of the contraction of the associated facial muscles.

LAWRENCE IAN REED is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Psychology, Skidmore College. Lawrence Ian Reed's Edge Bio Page

Molly Crockett: "The Neuroscience of Moral Decision Making"

Imagine we could develop a precise drug that amplifies people’s aversion to harming others; you won’t hurt a fly, everyone becomes Buddhist monks or something. Who should take this drug? Only convicted criminals—people who have committed violent crimes? Should we put it in the water supply? These are normative questions. These are questions about what should be done. I feel grossly unprepared to answer these questions with the training that I have, but these are important conversations to have between disciplines. Psychologists and neuroscientists need to be talking to philosophers about this and these are conversations that we need to have because we don’t want to get to the point where we have the technology and then we haven’t had this conversation because then terrible things could happen.

MOLLY CROCKETT is Associate Professor, Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford; Wellcome Trust Postdoctoral Fellow, Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging. Molly Crockett's Edge Bio Page

Hugo Mercier: "Toward The Seamless Integration Of The Sciences"

One of the great things about cognitive science is that it allowed us to continue that seamless integration of the sciences, from physics, to chemistry, to biology, and then to the mind sciences, and it's been quite successful at doing this in a relatively short time. But on the whole, I feel there's still a failure to continue this thing towards some of the social sciences such as, anthropology, to some extent, and sociology or history that still remain very much shut off from what some would see as progress, and as further integration.

HUGO MERCIER, a Cognitive Scientist, is an Ambizione Fellow at the Cognitive Science Center at the University of Neuchâtel. Hugo Mercier's Edge Bio Page

Jennifer Jacquet: "Shaming At Scale"

Shaming, in this case, was a fairly low-cost form of punishment that had high reputational impact on the U.S. government, and led to a change in behavior. It worked at scale—one group of people using it against another group of people at the group level. This is the kind of scale that interests me. And the other thing that it points to, which is interesting, is the question of when shaming works. In part, it's when there's an absence of any other option. Shaming is a little bit like antibiotics. We can overuse it and actually dilute its effectiveness, because it's linked to attention, and attention is finite. With punishment, in general, using it sparingly is best. But in the international arena, and in cases in which there is no other option, there is no formalized institution, or no formal legislation, shaming might be the only tool that we have, and that's why it interests me.

JENNIFER JACQUET is Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies, NYU; Researching cooperation and the tragedy of the commons; Author, Is Shame Necessary? Jennifer Jacquet's Edge Bio Page

Simone Schnall: "Moral Intuitions, Replication, and the Scientific Study of Human Nature"

In the end, it's about admissible evidence and ultimately, we need to hold all scientific evidence to the same high standard. Right now we're using a lower standard for the replications involving negative findings when in fact this standard needs to be higher. To establish the absence of an effect is much more difficult than the presence of an effect.

SIMONE SCHNALL is a University Senior Lecturer and Director of the Cambridge Embodied Cognition and Emotion Laboratory at Cambridge University. Simone Schnall's Edge Bio Page

David Rand: "How Do You Change People's Minds About What Is Right And Wrong?"

What all these different things boil down to is the idea that there are future consequences for your current behavior. You can't just do whatever you want because if you are selfish now, it'll come back to bite you. I should say that there are lots of theoretical models, math models, computational models, lab experiments, and also real world field data from field experiments showing the power of these reputation observability effects for getting people to cooperate.

DAVID RAND is Assistant Professor of Psychology, Economics, and Management at Yale University, and the Director of Yale University's Human Cooperation Laboratory. David Rand's Edge Bio page

L.A. Paul: "The Transformative Experience"

We're going to pretend that modern-day vampires don't drink the blood of humans; they're vegetarian vampires, which means they only drink the blood of humanely-farmed animals. You have a one-time-only chance to become a modern-day vampire. You think, "This is a pretty amazing opportunity, but do I want to gain immortality, amazing speed, strength, and power? Do I want to become undead, become an immortal monster and have to drink blood? It's a tough call." Then you go around asking people for their advice and you discover that all of your friends and family members have already become vampires. They tell you, "It is amazing. It is the best thing ever. It's absolutely fabulous. It's incredible. You get these new sensory capacities. You should definitely become a vampire." Then you say, " Can you tell me a little more about it?" And they say, "You have to become a vampire to know what it's like. You can't, as a mere human, understand what it's like to become a vampire just by hearing me talk about it. Until you're a vampire, you're just not going to know what it's going to be like."

L.A. PAUL is Professor of Philosophy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Professorial Fellow in the Arché Research Centre at the University of St. Andrews. L.A. Paul's Edge Bio page

Michael McCullough: "Two Cheers For Falsification"

What I want to do today is raise one cheer for falsification, maybe two cheers for falsification. Maybe it’s not philosophical falsificationism I’m calling for, but maybe something more like methodological falsificationism. It has an important role to play in theory development that maybe we have turned our backs on in some areas of this racket we’re in, particularly the part of it that I do—Ev Psych—more than we should have.

MICHAEL MCCULLOUGH is Director, Evolution and Human Behavior Laboratory, Professor of Psychology, Cooper Fellow, University of Miami; Author, Beyond Revenge. Michael McCullough's Edge Bio page

Also Participating

FIERY CUSHMAN is Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, Harvard University. JOSHUA KNOBE is an Experimental Philosopher; Associate Professor of Philosophy and Cognitive Science, Yale University. DAVID PIZARRO is Associate Professor of Psychology, Cornell University, specializing in moral judgment. LAURIE SANTOS is Associate Professor, Department of Psychology; Director, Comparative Cognition Laboratory, Yale University.

This year's Edge-Serpentine Gallery collaboration took place in London at part of the Serpentine's "Extinction Marathon: Visions of the Future" event, at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery's extension, designed by Zaha Hadid, on Oct. 18, 2014. The 2-hour event, which was live-streamed, is presented, here in its entiretly, on Edge.

The first hour was a converseation between Stewart Brand and Richard Prum on whether of not the prospect of "de-extinction" changes how we think about extinction. For the second hour, Molly Crockett introduced four Edgies—Helena Cronin, Jennifer Jacquet, Steve Jones, and Chiara Marletto, who gave 10-minute talks with their perspectives on the subject of extinction. This was followed by a panel.

NEW—COMPLETE VIDEO AND TEXT

Part I: "DE-EXTINCTION": STEWART BRAND & RICHARD PRUM

With Hans Ulrich Obrist and John Brockman

Does the prospect of "de-extinction" change how we think about extinction? Conservation science is shifting from being species-centric to function-centric, focussing on the overall health of ecosystems. Does the extinction of a species leave a "gap in nature" that can only be filled by returning the species to life and to the wild? Or will a functionally close relative serve? Is a de-extincted species really nothing more than a functionally close relative anyway? If it is too difficult and expensive to revive every extinct species, what are the criteria for deciding which ones to work on? Humans are the ones deciding. What ethics and aesthetics should guide those decisions?

STEWART BRAND is the Founder of the "The Whole Earth Catalog" and Co-founder of The Long Now Foundation and Revive and Restore; Author, Whole Earth Discipline.

Stewart Brand's Edge Bio Page

RICHARD PRUM is an Evolutionary Ornithologist at Yale University, where he is the Curator of Ornithology and Head Curator of Vertebrate Zoology in the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. He is working on a book about duck sex, aesthetic evolution, and the origin of beauty.

Richard Prum's Edge Bio Page

[Continue to Part I—Video & Text]

Part II: "EDGIES ON EXTINCTION"

Molly Crockett introduces and moderates an event of four 10-minute talks by Helena Cronin, Jennifer Jacquet, Steve Jones, and Chiara Marletto, followed by a discussion joined by Hans Ulrich Obrist, and John Brockman.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST: When we spoke with John Brockman about the Extinction Marathon he suggested, as a second part—as I mentioned in previous marathons we got the Edge community to realize maps and different formulas, and John thought today it would be wonderful to do a panel with UK based scientists who are part of the Edge community. We are extremely delighted that we now will have four presentations by Helena Cronin, by Chiara Marletto, by Jennifer Jacquet, and by Steve Jones. We welcome Steve Jones back to the Serpentine because he was part of the 2007 Experiment Marathon with Olafur Eliasson. The entire panel will be introduced by Molly Crockett. Molly is an associate professor for experimental psychology and fellow of Jesus college at the University of Oxford. She holds a Ph.D. in experimental psychology from Cambridge and a B.S. in neuroscience from UCLA. Dr. Crockett studies the neuroscience and psychology of altruism, of morality, and self-control. Her work has been published in many top academic journals including Science, PNAS, and also Neuron. Molly Crockett will now introduce Helena, Chiara, Jennifer, and Steve. We then, together with Molly and all the speakers and John, give a panel after that.

MOLLY CROCKETT: I'm very, very pleased to introduce Helena Cronin. She's the co-director of the Center for Philosophy of Natural and Social Science and the director of Darwin at LSE at the London School of Economics. She has many notable publications including the edited series, Darwinism Today, and the award winning, The Ant and the Peacock: Altruism and Sexual Selection from Darwin to Today, that has been featured in the New York Times' Best Books and Nature's Best Science Books of the Year. Her current research interests focus on the evolutionary understanding of sex differences. Let's give a very warm welcome to Helena and welcome her to the stage. ...

... A strange thing happened on the way to a better world in pursuit of an admirable quest, that is, a world free of sex discrimination where you’re judged on your own qualities and not your sex. Truth and falsity went topsy-turvy. The truth—the silence of sex differences—became dangerous, unmentionable, and in its place the conventional wisdom, which is a ragbag of ideas that have long been extinct but are kept ghoulishly alive by popularity, became the entrenched orthodoxy influencing public thinking, agendas and policy-making, and completely crowding out science and sense.

... A strange thing happened on the way to a better world in pursuit of an admirable quest, that is, a world free of sex discrimination where you’re judged on your own qualities and not your sex. Truth and falsity went topsy-turvy. The truth—the silence of sex differences—became dangerous, unmentionable, and in its place the conventional wisdom, which is a ragbag of ideas that have long been extinct but are kept ghoulishly alive by popularity, became the entrenched orthodoxy influencing public thinking, agendas and policy-making, and completely crowding out science and sense.

My aim is to show you why the current orthodoxy should be abandoned and why, if you really care about a fairer world, the science does matter. It matters profoundly. I’m going to take two examples, both about the professions, because they very well epitomize the orthodox litany: how society systematically discriminates against women, and how at work they are victims of pervasive sexism. ...

HELENA CRONIN is the Co-Director of LSE's Centre for Philosophy of Natural and Social Science; Author, The Ant and the Peacock: Altruism and Sexual Selection from Darwin to Today. Helena Cronin's Edge Bio Page

There is a new fundamental theory of physics that's called constructor theory, and was proposed by David Deutsch who pioneered the theory of the universe of quantum computer. David and I are working this theory together. The fundamental idea in this theory is that we forumlate all laws of physics in terms of what tasks are possible, what are impossible, and why. In this theory we have an exact physical characterization of an object that has those properties, and we call that knowledge. Note that knowledge here means knowledge without knowing the subject, as in the thoery of knowledge of the philosopher, Karl Popper.

There is a new fundamental theory of physics that's called constructor theory, and was proposed by David Deutsch who pioneered the theory of the universe of quantum computer. David and I are working this theory together. The fundamental idea in this theory is that we forumlate all laws of physics in terms of what tasks are possible, what are impossible, and why. In this theory we have an exact physical characterization of an object that has those properties, and we call that knowledge. Note that knowledge here means knowledge without knowing the subject, as in the thoery of knowledge of the philosopher, Karl Popper.

We’ve just come to the conclusion that the fact that extinction is possible means that knowledge can be instantiated in our physical world. In fact, extinction is the very process by which that knowledge is disabled in its ability to remain instantiated in physical systems because there are problems that it cannot solve. With any luck that bit of knowledge can be replaced with a better one. ...

CHIARA MARLETTO is a Junior Research Fellow at Wolfson College and Postdoctoral Research Assistant at the Materials Department, University of Oxford. Chiara Marletto's Edge Bio Page

I dream about the sea cow or imagine what they would be like to see in the wild, but the case of the Pinta Island giant tortoise was a particularly strange feeling for me personally because I had spent many afternoons in the Galapagos Islands when I was a volunteer with the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society in Lonesome George’s den with him. If any of you visited the Galapagos, you know that you can even feed the giant tortoises that are in the Charles Darwin Research Station. This is Lonesome George here.

I dream about the sea cow or imagine what they would be like to see in the wild, but the case of the Pinta Island giant tortoise was a particularly strange feeling for me personally because I had spent many afternoons in the Galapagos Islands when I was a volunteer with the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society in Lonesome George’s den with him. If any of you visited the Galapagos, you know that you can even feed the giant tortoises that are in the Charles Darwin Research Station. This is Lonesome George here.

He lived to a ripe old age but failed, as they pointed out many times, to reproduce. Just recently, in 2012, he died, and with him the last of his species. He was couriered to the American Museum of Natural History and taxidermied there. A couple weeks ago his body was unveiled. This was the unveiling that I attended, and at this exact moment in time I can say that I was feeling a little like I am now: nervous and kind of nauseous, while everyone else seemed calm. I wasn’t prepared to see Lonesome George. Here he is taxidermied, looking out over Central Park, which was strange as well. At that moment realized that I knew the last individual of this species to go extinct. That presents this strange predicament for us to be in in the 21st century—this idea of conspicuous extinction. ...

JENNIFER JACQUET is Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies, NYU; Researching cooperation and the tragedy of the commons; Author, Is Shame Necessary? Jennifer Jacquet's Edge Bio Page

... A strange thing happened on the way to a better world in pursuit of an admirable quest, that is, a world free of sex discrimination where you’re j

... A strange thing happened on the way to a better world in pursuit of an admirable quest, that is, a world free of sex discrimination where you’re j

What I wanted to talk about is somewhat of a parallel of that in human populations. If you were to go to a textbook on human biology from the time of Darwin or a bit later, you would certainly get an image that looked a bit like this. This is an image of the so-called races of humankind—racial types, as they called them. I’m not going to go into the question of whether there are real races of humankind because there aren’t. It’s interesting to note that until quite recently people assumed, and scientists assumed too, that the human species was divided into distinct groups that were biologically different from each other and had been isolated from each other for a long, long time.

Well, to some extent that was true. Until quite recently, human populations were isolated from each other. That’s changing quite quickly. ...

STEVE JONES is an Emeritus Professor of Genetics at University College London. Steve Jones's Edge Bio Page

MOLLY CROCKETT is an Associate Professor in the Department of Experimental Psychology at the University of Oxford; Wellcome Trust Postdoctoral Fellow at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging. Molly Crockett's Edge Bio Page

MOLLY CROCKETT is an Associate Professor in the Department of Experimental Psychology at the University of Oxford; Wellcome Trust Postdoctoral Fellow at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging. Molly Crockett's Edge Bio Page

HANS ULRICH OBRIST is the Co-director of the Serpentine Gallery in London; Author, Ways of Curating. Hans Ulrich Obrist's Edge Bio Page

JOHN BROCKMAN is the Editor and Publisher of Edge.org; Chairman of Brockman, Inc.; Author, By the Late John Brockman, The Third Culture. John Brockman's Edge Bio Page

[Continue to Part II — Video & Text]

EDGE & SERPENTINE GALLERY

Previous Edge-Serpentine collaborations have included:

"Formulae for the 21st Century" (2007)

"The Table-Top Experiment Marathon" (2007)

"Maps For The 21st Century" (2010)

"Information Gardens" (2011)

SPEAKING OF EXTINCTIONS....

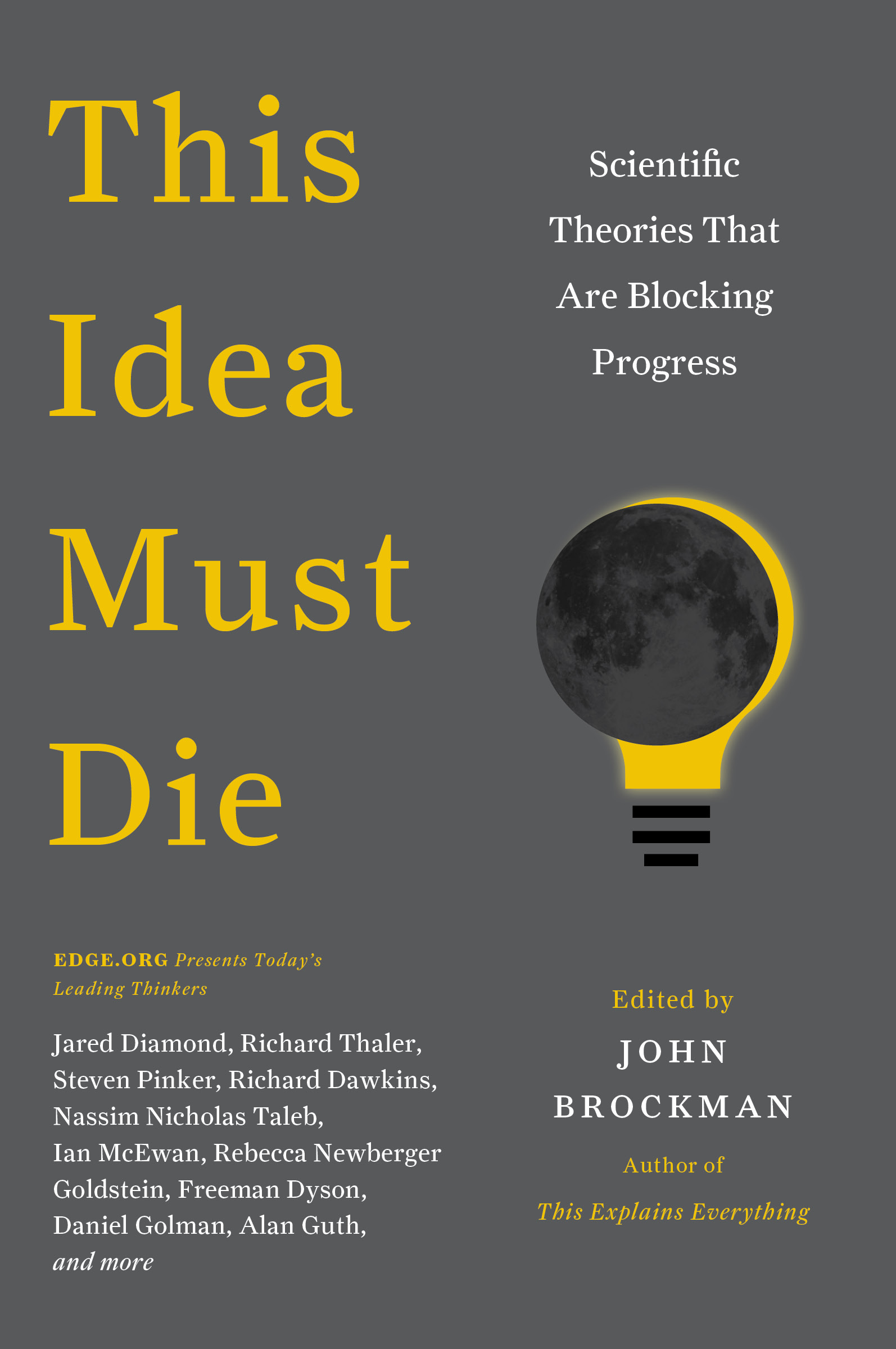

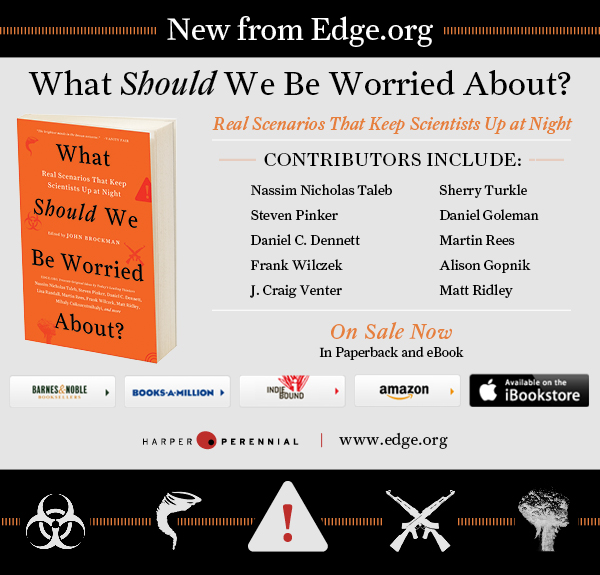

Edge's own contribution to the conversation will be published in February:

EDGE: LIVE, IN LONDON

This year's collaboration with the Serpentine Gallery in London was part of the "Extinction Marathon: Visions of the Future" event, which will took place in the Serpentine Sackler Gallery's extension, designed by Zaha Hadid, on Oct. 18th. The entire event which was live-streamed, will be presented on Edge.

An EDGE Conversation: "DE-EXTINCTION": Stewart Brand & Richard Prum

with Hans Ulrich Obrist & John Brockman

Does the prospect of "de-extinction" change how we think about extinction? Conservation science is shifting from being species-centric to function-centric, focussing on the overall health of ecosystems. Does the extinction of a species leave a "gap in nature" that can only be filled by returning the species to life and to the wild? Or will a functionally close relative serve? Is a de-extincted species really nothing more than a functionally close relative anyway? If it is too difficult and expensive to revive every extinct species, what are the criteria for deciding which ones to work on? Humans are the ones deciding. What ethics and aesthetics should guide those decisions?

STEWART BRAND is the Founder of the "The Whole Earth Catalog" and Co-founder of The Long Now Foundation and Revive and Restore; Author, Whole Earth Discipline.

RICHARD PRUM is an Evolutionary Ornithologist at Yale University, where he is the Curator of Ornithology and Head Curator of Vertebrate Zoology in the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. He is working on a book about duck sex, aesthetic evolution, and the origin of beauty.

"EDGIES ON EXTINCTION": 10 Minute talks by Helena Cronin, Jennifer Jacquet, Steve Jones, and Chiara Marletto, and an EDGE discussion joined by Molly Crockett, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and John Brockman.

I dream about the sea cow or imagine what they would be like to see in the wild, but the case of the Pinta Island giant tortoise was a particularly strange feeling for me personally because I had spent many afternoons in the Galapagos Islands when I was a volunteer with the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society in Lonesome George’s den with him. If any of you visited the Galapagos, you know that you can even feed the giant tortoises that are in the Charles Darwin Research Station. This is Lonesome George here.

He lived to a ripe old age but failed, as they pointed out many times, to reproduce. Just recently, in 2012, he died, and with him the last of his species. He was couriered to the American Museum of Natural History and taxidermied there. A couple weeks ago his body was unveiled. This was the unveiling that I attended, and at this exact moment in time I can say that I was feeling a little like I am now: nervous and kind of nauseous, while everyone else seemed calm. I wasn’t prepared to see Lonesome George. Here he is taxidermied, looking out over Central Park, which was strange as well. At that moment realized that I knew the last individual of this species to go extinct. That presents this strange predicament for us to be in in the 21st century—this idea of conspicuous extinction. [Continue...]

JENNIFER JACQUET is an Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies at NYU researching cooperation and the tragedy of the commons; Author, Is Shame Necessary? Jennifer Jacquet's Edge Bio Page

~ ~ ~ ~

There is a new fundamental theory of physics that’s called constructor theory, and was proposed by David Deutsch who pioneered the theory of the universe of quantum computer. David and I are working this theory together. The fundamental idea in this theory is that we formulate all laws of physics in terms of what tasks are possible, what are impossible, and why. In this theory we have an exact physical characterization of an object that has those properties, and we call that knowledge. Note that knowledge here means knowledge without knowing the subject, as in the theory of knowledge of the philosopher, Karl Popper.

We’ve just come to the conclusion that the fact that extinction is possible means that knowledge can be instantiated in our physical world. In fact, extinction is the very process by which that knowledge is disabled in its ability to remain instantiated in physical systems because there are problems that it cannot solve. With any luck that bit of knowledge can be replaced with a better one. [Continue...]

CHIARA MARLETTO is a Junior Research Fellow at Wolfson College and Postdoctoral Research Assistnat at the Materials Department at the University of Oxford. Chiara Marletto's Edge Bio Page

~ ~ ~ ~

What I wanted to talk about is somewhat of a parallel of that in human populations. If you were to go to a textbook on human biology from the time of Darwin or a bit later, you would certainly get an image that looked a bit like this. This is an image of the so-called races of humankind—racial types, as they called them. I’m not going to go into the question of whether there are real races of humankind because there aren’t. It’s interesting to note that until quite recently people assumed, and scientists assumed too, that the human species was divided into distinct groups that were biologically different from each other and had been isolated from each other for a long, long time.