Here's a sampling:

... "The Apple idea is that instead of the personal computer model where people own their own information, and everybody can be a creator as well as a consumer, we're moving towards this iPad, iPhone model where it's not as adequate for media creation as the real media creation tools, and even though you can become a seller over the network, you have to pass through Apple's gate to accept what you do, and your chances of doing well are very small, and it's not a person to person thing, it's a business through a hub, through Apple to others, and it doesn't create a middle class, it creates a new kind of upper class. ... Google has done something that might even be more destructive of the middle class, which is they've said, "Well, since Moore's law makes computation really cheap, let's just give away the computation, but keep the data." And that's a disaster.

... If we enter into the kind of world that Google likes, the world that Google wants, it's a world where information is copied so much on the Internet that nobody knows where it came from anymore, so there can't be any rights of authorship. However, you need a big search engine to even figure out what it is or find it. They want a lot of chaos that they can have an ability to undo. ... when you have copying on a network, you throw out information because you lose the provenance, and then you need a search engine to figure it out again. That's part of why Google can exist. Ah, the perversity of it all just gets to me.

... What Wal-Mart recognized is that information is power, and by using network information, you could consolidate extraordinary power, and so have information about what could be made where, when, what could be moved where, when, who would buy what, when for how much? By coalescing all of that, and reducing the unknowns, they were able to globalize their point of view so they were no longer a local player, but they essentially became their own market, and that's what information can do. The use of networks can turn you from a local player in a larger system into your own global system.

... The reason this breaks is that there's a local-global flip that happens. When you start to use an information network to concentrate information and therefore power, you benefit from a first arrival effect, and from some other common network effects that make it very hard for other people to come and grab your position. And this gets a little detailed, but it was very hard for somebody else to copy Wal-Mart once Wal-Mart had gathered all the information, because once they have the whole world aligned by the information in their server, they created essentially an expense or a risk for anybody to jump out of that system. That was very hard. ... In a similar way, once you are a customer of Google's ad network, the moment that you stop bidding for your keyword, you're guaranteeing that your closest competitor will get it. It's no longer just, "Well, I don't know if I want this slot in the abstract, and who knows if a competitor or some entirely unrelated party will get it." Instead, you have to hold on to your ground because suddenly every decision becomes strategic for you, and immediately. It creates a new kind of glue, or a new kind of stickiness.

... It can become such a bizarre system. What you have now is a system in which the Internet user becomes the product that is being sold to others, and what the product is, is the ability to be manipulated. It's an anti-liberty system, and I know that the rhetoric around it is very contrary to that.

... Essentially what happened with finance is a larger scale, albeit more abstract version of what happened with Wal-Mart, where a global system was optimized by being able to build data that could be concentrated locally using a computer network. It tremendously enriched the people who ran the network. It seemed to create savings for people initially who were the end users, the leafs of the network, very much as Google, or Groupon, seem to save them money initially. But then in the long-term it took away more from the income prospects of people than it could offer them in savings, very much as Wal-Mart did. ... This is the pattern that we'll see repeated again and again as new applications of computer networks come up, unless we decide to monetize what people do with their hearts and brains. What we have to do to create liberty in the future is to monetize more and more instead of monetize less and less, and in particular we have to monetize more and more of what ordinary people do, unless we want to make them into wards of the state. That's the stark choice we have in the long-term.

...if you're adding to the network, do you expect anything back from it? And since we've been hypnotized in the last eleven or twelve years into thinking that we shouldn't expect anything for what we do with our hearts or our minds online, we think that our own contributions aren't worth money, very much like we think we shouldn't be paid for parenting, or we shouldn't be paid for raking our own yard. In those cases you are paid in a sense because there's still something that becomes part of you in your life, for all that you did. ... But in this case we have this idea that we put all this stuff out there and what we get back are intangible or abstract benefits of reputation, or ego-boosting. Since we're used to that bargain, we're impoverished compared to the world that could have been and should have been when the Internet was initially conceived. The world that would create a strengthened middle class through what people do, by monetizing more and more instead of less and less. It's possible that that world could have never come about, but that was never tested. If we are absolutely convinced that this third way is impossible, and that we have to choose between "The Matrix" or Marx, if those are our only two choices, it makes the future dismal, and so I hope that a third way is possible, and I'm certainly going to do everything possible to try to push it.

Read on. Or better yet, treat yourself to an interesting hour of watching the video and engaging with Lanier and his ideas.

JARON LANIER is a computer scientist, composer, and visual artist. He is the author of You Are Not A Gadget: A Manifesto.

The Reality Club: Dougas Rushkoff

THE LOCAL-GLOBAL FLIP, OR, "THE LANIER EFFECT"

[JARON LANIER:] One of the things I've been thinking about is how computation is a human-centric concept. In the abstract, aliens don't recognize our bits. There has to be a cultural setup for us to recognize stored information. And that cultural setup can bring into it all kinds of fundamental ideas which could have a huge effect on how society runs, how the economy works, and how our lives are put together.

I've focused quite a lot on how this stealthy component of computation can affect our sense of ourselves, what it is to be a person. But lately I've been thinking a lot about what it means to economics.

In particular, I'm interested in a pretty simple problem, but one that is devastating. In recent years, many of us have worked very hard to make the Internet grow, to become available to people, and that's happened. It's one of the great topics of mankind of this era. Everyone's into Internet things, and yet we have this huge global economic trouble. If you had talked to anyone involved in it twenty years ago, everyone would have said that the ability for people to inexpensively have access to a tremendous global computation and networking facility ought to create wealth. This ought to create wellbeing; this ought to create this incredible expansion in just people living decently, and in personal liberty. And indeed, some of that's happened. Yet if you look at the big picture, it obviously isn't happening enough, if it's happening at all.

The situation reminds me a little bit of something that is deeply connected, which is the way that computer networks transformed finance. You have more and more complex financial instruments, derivatives and so forth, and high frequency trading, all these extraordinary constructions that would be inconceivable without computation and networking technology.

At the start, the idea was, "Well, this is all in the service of the greater good because we'll manage risk so much better, and we'll increase the intelligence with which we collectively make decisions." Yet if you look at what happened, risk was increased instead of decreased.

In parallel it seems as though the middle classes have been having trouble all around the world, not just in the U.S., but in all developed societies at the same time that the Internet has been rising. I'm concerned that it's not a matter of the Internet doing some good, but not enough good to undo unrelated coincidental troubles. I'm afraid the Internet, as we've conceived of it thus far, has been part of the problem. I'm also interested in the idea that if we conceive of it differently, it could be a solution.

This brings us back, literally thousands of years to an ancient discussion that continues to this day about exactly how people can make a living, or make their way when technology gets better. There is an Aristotle quote about how when the looms can operates themselves, all men will be free. That seems like a reasonable thing to say, a precocious thing for somebody to have said in ancient times. If we zoom forward to the 19th century, we had a tremendous amount of concern about this question of how people would make their way when the machines got good. In fact, much of our modern intellectual world started off as people's rhetorical postures on this very question.

Marxism, the whole idea of the left, which still dominates the Bay Area where this interview is taking place, was exactly, precisely about this question. This is what Marx was thinking about, and in fact, you can read Marx and it sometimes weirdly reads likes a Silicon Valley rhetoric. It's the strangest thing; all about "boundaries falling internationally," and "labor and markets opening up," and all these things. It's the weirdest thing.

In fact, I had the strange experience years ago, listening to some rhetoric on the radio ... it was KPFA, in fact, the lefty station ... and I thought, "Oh, God, it's one of these Silicon startups with their rhetoric about how they're going to bring down market barriers", and it turned out to be an anniversary reading of "Das Kapital". The language was similar enough that one could make the mistake.

The origin of science fiction was exactly in this same area of concern. H.G. Wells' The Time Machine foresees a future in which there are the privileged few who benefit from the machines, and then there are the rest who don't, and both of them become undignified, lesser creatures. Separate species. The first literary description of the Internet, which preceded the invention of the computer by many years, was E. M. Forster's The Machine Stops, which continues the theme. And another nice example is Kurt Vonnegut's novel, Player Piano, which is yet another statement of it.

But at any rate, let's get to what the question is. Let's suppose that machines get good enough that one can say a lot of people are extraneous, that the machines are doing what needs to be done. It has to immediately be said that this wouldn't in fact happen, because software will probably be buggy and machines will be unreliable, so there would still have to be human oversight. The machines will screw up. The way I phrased it was careful—"one can say"—because the crucial thing about very high-functioning machines, artificial intelligences and what not, is how we conceive of the things that the machines can't do, whether those are considered real jobs for people or not.

Let me give you just a couple of examples that are right on the threshold of becoming mainstream. One of them is a self-driving vehicle. Not only Google, but also some other researchers in Europe and in Asia have been demonstrating cars that are quite effective at driving themselves around. The reasons for wanting cars that can be self-driving are so extraordinarily powerful ... you couldn't have better reasons.

Human are terrible drivers. We kill each other in car accidents so frequently that car accidents are a much more serious problem than wars, terrorism, a great many diseases. It's one of our biggest sources of death and pain, and it's awful. It's very unlikely that robots could drive as badly as people. That's compelling.

But there's much more. If the cars could coordinate with each other, instead of people fighting each other in little tiny ego-wars to merge between lanes on the freeway causing this huge backup going miles back, the cars could coordinate and cleanly merge together, taking full advantage of the hypothetical bandwidth of the freeway. They could be cognizant of their wakes, and they could manage the airflow together to improve their efficiency. A lot of streetlights could go away. They would simply know that there's no other car coming, and there's no pedestrian, and they could just proceed through without stopping, which would be a huge, huge gain for energy efficiency, since you wouldn't have to accelerate from a stop as often. And it goes on and on. There are just many, many, many benefits.

Then there are some problems. One of the problems is that when there is a screw-up, it could be a huge one. If a whole freeway of cars hit each other because of a snag, it would be something like a plane crash instead of a little tiny thing. That's conceivable when there are a lot of cars connected together, and moving rapidly under the same software system. Then, of course, there's the existential issue of losing freedom, how do people feel about that? All of these things have been talked about a great deal.

But finally, there's this very interesting issue, that you can't make it 100 percent. If people are going to be people at all, somebody has to tell the car where to go and something about how to do it, and there has to be some failsafe, and there has to be some human responsibility if not on the part of the people who are passengers in the car, at least somewhere. And here's where we get into very, very interesting territory.

I just listed a bunch of ways that automating driving would create efficiencies. It would save huge amounts of money because there would be fewer people going to the hospital, there's less fuel, and people get places faster. There is this huge increase in efficiency, but the interesting thing is that increasing efficiency by itself doesn't employ people. There is a difference between saving and making money when you're unemployed. Once you're already rich, saving money and making money is the same thing, but for people who are on the bottom or even in the middle classes, saving money doesn't help you if you don't have the money to save in the first place.

If you look at the labor prospects of the middle classes, a whole lot of middle class people are behind a wheel. There's a whole bunch of cabbies, and truck drivers, et cetera, and we're talking about throwing all of those people out of work—forever—pretty soon, basically. It's very, very likely that at some point, not next year, but this century at the very least, and probably the early part of the century, that it would just be inconceivable to put a person behind the wheel of some big truck. People will just think it's insane. Similarly cabs will be safer in an automated mode. What do all those people do?

This becomes interesting. There aren't that many options, and let me list what those options are.

One option is the one that Marx advocated. That option is: The society is saving a lot of money, it's getting more efficient, so we'll apply that to taking care of the unneeded people. In that case, well it's a tricky one… Because in every example in which there have been very large numbers of people who were just taken care of by a society, it eventually breaks.

The way that can work is maybe if people are broken into societies that are very ideologically, ethnically, and in other ways homogenous so they somehow can accept each other. That way, they can accept similar tradeoffs, and coordinate with each other. It'd be very hard to do it in our heterogeneous crazy society filled with a lot of surprises. People would have to rely purely on democracy; you couldn’t rely on capitalism anymore for a sense of liberty. You’d have to argue with people and agree on things. Sometimes that's just impossible. Government can only work so well.

The beauty of money is it creates a system of people leaving each other alone by mutual agreement. It's the only invention that does that that I'm aware of. In a world of finite limits where you don't have an infinite West you can expand into, money is the thing that gives you a little bit of peace and quiet, where you can say, "It's my money, I'm spending it".

I know that there are a great many leftists around here who think that when the machines get good the government will support everybody, and somehow we'll agitate for our rights, and everybody will have this kind of liberty and ability to do as they please. But I find that very hard to believe. I just don't think that that would work. Even in the places that are called anarchistic, in fact, what happens is a new kind of order, which is often very oppressive if you don't happen to fit in. In San Francisco you can be attacked by mobs of bicycling advocates who've occasionally been quite ruthless because they believe in bicycles, and they think that they're the most enlightened, free people in the world, and yet if somebody doesn't agree with them, then they have trouble.

Similarly, Burning Man, which people who fit in at Burning Man must perceive is the most open, accepting place in the world is, in fact, extraordinarily unaccepting of people who don't conform. Just a mild example of that is if you show up in an RV you're pooh-poohed by a lot of people.

This hope that socialism can preserve liberty is pretty unlikely to work out. I hesitate to say that because most of the people who say that are these rigid Tea Party nut cases these days in the United States. I hate to be saying something that sounds similar, but that doesn't make it untrue. It still is a problem.

All right, so let's leave aside Marx's answer. Another possibility is that the extraneous people just suffer, and are maybe given inexpensive amusements. This is also foreseen in science fiction quite a lot. Most recently as a pop phenomenon, "The Matrix" movies might have expressed that the most, where there's this conceit that somehow people's human bodies are useful as batteries, although anyone who sees the movie is thinking, "Oh, there's got to be a better battery. Why would they keep the people around?" So even as batteries, people are unlikely to be needed.

And there is a disturbing sense in which I feel like that's the world we're entering. I'm astonished at how readily a great many people I know, young people, have accepted a reduced economic prospect and limited freedoms in any substantial sense, and basically traded them for being able to screw around online. There are just a lot of people who feel that being able to get their video or their tweet seen by somebody once in a while gets them enough ego gratification that it's okay with them to still be living with their parents in their 30s, and that's such a strange tradeoff. And if you project that forward, obviously it does become a problem.

What that leads to is the world that Wells and Kurt Vonnegut and many others wrote about, where there just is enough virtual bread and circuses, just barely enough to keep the poor in check, and perhaps somehow not breeding, and they just kind of either wither away through attrition or something. Or medicine gets good enough and expensive enough that those on the wealthy side of it live and those on the other, once again through attrition, fade away.

Another example that is quite astonishing, one that will be recognized by future historians as an extraordinary phenomenon in the 21st century, is that the aging populations are buying into their own impoverishment. There's this strange way in which people who are older tend to be conservative, and what conservative means now is no government: "Don't you dare support my dialysis, don't you dare support my nursing home expenses! That reduces my liberty! I need my freedom and my options."

But if you look at how this transformation has come about, where the elderly are, for the most part, advocating their own impoverishment and misery, you find the same thing, this prevalence of social media, new media. You tend to find "conservative," nutty politics using social media better than mainstream sensible stuff. And that's true both on the left and the right, but it's the right that's taken off with it, and that's striking to me. Of course, that story is still unfolding, so we don't know how it will turn out, but it's absolutely remarkable.

To me, a lot of the culture of youth seems to be using the Internet as a form of denialism about their reduced prospects. They're like, "Well, sure we can't get a job and we need to live with our parents, but we can tweet", or something. "Let us tweet!"

This "rights" kind of stance, as opposed to a "wealth" kind of stance, it's exactly the mirror image of what you see in Tea Party older America, of "we don't want our healthcare paid for. What we want is the right to not have our healthcare paid for, and that's more important to me."

It's very strange, this notion of impoverishment and lack of prospects, but this absoluteness of expression and speech. And in a way maybe that's admirable, maybe there is something about that that's very American, and very pure. I don't know. But at any rate, it's not sustainable, whatever it is. I don't think it leads to a workable scenario, and I also think it just includes too much suffering and cruelty.

Just to recap where the argument is so far, I've described two ways to cope with machines getting good.

One is a Marxist way, where you have some form of socialism, some institutional attempt for everybody to get along and use politics to arrange for their own liberty instead of some more abstract mechanism like money, and I'm concerned that that's not realistic given human nature.

A second way is for people to just suffer, and for the poor to wither away through attrition, as they can't afford medicine or some scenario like that over time. I should say that this notion of the poor withering away does seem to be normative right now, and it concerns me a great deal.

I believe there is a third way, which is a better way, and it happens to have also been the initial idea for the Internet, interestingly enough. My poster boy for expressing this is Ted Nelson, the eccentric character who initially proposed the Web, or something like it ... it wasn't called the Web then ... as early as 1960, which is over a half century ago, amazingly, when I was born.

Ted's idea was that there would be a universal market place where people could buy and sell bits from each other, where information would be paid for, and then you'd have a future where people could make a living and earn money from what they did with their hearts and heads in an information system, the Internet, thereby solving this problem of how to have a middle class, and how to have liberty. To expect liberty from democracy without a middle class is hopeless because without a middle class you can't have democracy. The whole thing falls a part.

I remember when I first met Ted as a teenager, we talked about how you need to have some system like this where people are making a living with their hearts and heads, and trading online, and this was before the word "online" even existed in the way we know it today. It's the only way to have a future of liberty.

Silicon Valley totally screwed up on this. We were doing a great job through the turn of the century. In the '80s and '90s, one of the things I liked about being in the Silicon Valley community was that we were growing the middle class. The personal computer revolution could have easily been mostly about enterprises. It could have been about just fighting IBM and getting computers on desks in big corporations or something, instead of this notion of the consumer, ordinary person having access to a computer, of a little mom and pop shop having a computer, and owning their own information. When you own information, you have power. Information is power. The personal computer gave people their own information, and it enabled a lot of lives.

At the turn of the century we turned it all around, and there's two ways it got turned around. One exemplified perhaps by Google, and another way by Apple, although I should point out at this point I'm working with Microsoft, which to some people's minds might make me partisan in this. I have a special arrangement with them where they even encourage me to criticize them in public, and I do, and many of the things I critique here can be applied, as well, to various Microsoft businesses (Bing does exactly what Google does) and so it's not about company versus company stuff. Also the people at Apple and Google are my friends, and I've made money from Google. It's not personal. I like Google. And it's not about company rivalries, and I hope I can persuade people of that.

But at any rate, the Apple idea is that instead of the personal computer model where people own their own information, and everybody can be a creator as well as a consumer, we're moving towards this iPad, iPhone model where it's not as adequate for media creation as the real media creation tools, and even though you can become a seller over the network, you have to pass through Apple's gate to accept what you do, and your chances of doing well are very small, and it's not a person to person thing, it's a business through a hub, through Apple to others, and it doesn't create a middle class, it creates a new kind of upper class.

Google has done something that might even be more destructive of the middle class, which is they've said, "Well, since Moore's law makes computation really cheap, let's just give away the computation, but keep the data." And that's a disaster.

What's happened now is that we've created this new regimen where the bigger your computer servers are, the more smart mathematicians you have working for you, and the more connected you are, the more powerful and rich you are. (Unless you own an oil field, which is the old way.) II benefit from it because I'm close to the big servers, but basically wealth is measured by how close you are to one of the big servers, and the servers have started to act like private spying agencies, essentially.

With Google, or with Facebook, if they can ever figure out how to steal some of Google's business, there's this notion that you get all of this stuff for free, except somebody else owns the data, and they use the data to sell access to you, and the ability to manipulate you, to third parties that you don't necessarily get to know about. The third parties tend to be kind of tawdry.

We tend to now be courting the seedier side of capitalism more than the dignified side of capitalism. There tend to be a lot of ambulance chasers, and snake oil salespeople who become our customers. Not all. There are some stories that are very positive. There's the occasional person who builds a career by blogging, or getting on YouTube, or who can build a small business by selling ads on some of these services. Those people exist, but there's a Horatio Alger quality where there just aren't enough of them to create a middle class. They create a false hope rather than a real trend. And it's plain as day that that's the truth, that there aren't hoards and hoards of these people, but just tokens.

It's funny to say that because I'll often get a lot of pushback and they'll say, "No, no, no. There are all these people who are being empowered by all this stuff on the Internet that's free", and I'll say, "Well, show me. Where's all the wealth? Where's the new middle class of people who are doing this?" They don't exist. They just aren't there. We're losing the middle class, and we should be saving it. We should be strengthening it.

If we used to be a bell curve society, we're ending up as a U-shaped society, turning into what Brazil used to be, or something like that, that's where America is going. You can see the Apple model, and it's not just Apple, but this notion of the elite-controlled thing serving the upper horn of the U, and you can see the Google model, which is like the seedy pawn shop and cash store kind of approach to the Internet where, "Oh, we'll give you coupons, and we'll sell advertising to you, and it's free, free, free, free, free." That attaches itself to the lower horn of the U.

The thing that I'm thinking about is the Ted Nelson approach, the third way where people buy and sell each other information, and can live off of what they do with their hearts and minds as the machines get good enough to do what they would have done with their hands. That thing is the thing that could grow the middle back.

Then the crucial element of that is what we can call a "social contract" where people would pay for stuff online from each other if they were also making money from it. When people get nothing from a society, they eventually just riot. And to my mind, that's kind of what's going on on the Internet. Basically, people can expect free stuff from the Internet but they don't expect wealth from the Internet, which to me makes it a failed technology at this point, although I hope it's revivable. I'm sure it is. I'm positive it is.

And so when all you can expect is free stuff, you don't respect it, it doesn't offer you enough to give you a social contract. What you can seek on the Internet is you can seek some fine things, you can seek friendship and connection, you can seek reputation and all these things that are always talked about, you just can't seek cash. And it tends to create a lot of vandalism and mob-like behavior. That's what happens in the real world when people feel hopeless, and don't feel that they're getting enough from society. It happens online.

I feel certain that if people had an opportunity to make a living from it, some number of them would be drawn to become scammier, of course, because that's also part of human nature, but on the whole, it would reinforce a social contract which people would buy into. They would treat it as something valuable in a way that—even with all the talk about the Internet and these incessant clichéd ways in which every story has to be Internet-centric if there is any plausible way it can be, even with all that—it still could be so much more, because it could be the way that we can make a living from our hearts and heads. That's what it must be. It must become that somehow.

I promised I'd mention two ways that the machines are getting good, and I just mentioned driverless cars. I should say a little bit more about that, perhaps. The interesting contest that will happen—in about ten years is when this will come to head—is the contest between a purely driverless car, where you just get in a robot taxi and you say, "Take me to the airport", and it says, "Okay, airport", and then we go (Makes Zooming Sound), and then it shows you ads along the way, or forces you to drive by billboards, or forces you to a particular convenience store if you need to pick up something, or whatever the scam is that would come about from a Google-driven car. That's one way.

There's another way to do it, which is you still drive the car, but with a fancy user interface, where you have autonomy much of the time, however when there is either an intersection with other cars approaching, or there's congestion on a freeway, or an imminent collision, if there is some other reason that automation is better, it can take over. But in the meantime it gives you fantastic user interface. It helps you be a much better driver, and get where you want faster if that's your desire, or whatever it is. That's like an augmented reality car blended with a fully automated car, and that might be the thing that works better. If it does, there's more of a human role, and there's more potential for employment. There might even be a cabby driving that thing, that's conceivable. There might even be a trucker in that truck, and it might work better. But anyway, that's something that we'll sort out.

Another thing like driverless cars that's going to come along and have this huge impact is 3-D printing, and automated manufacturing at a small-distributed scale in other ways. This is a hobbyist phenomenon right now where you have a machine that takes some gloop, that connects to your computer, and then the gloop is printed out into something you might like, like a new Frisbee, or coat hanger, or clarinet mouthpiece, whatever it is. As this gets more and more sophisticated, it becomes possible that more and more things can be manufactured onsite instead of made in China or wherever, and then moved over through a huge transportation network. The system will remember what it made, so it knows what each thing is made of, and how to take it a part, so recycling can become vastly more automated, more efficient rapidly, and so there is a whole systemic potential improvement in efficiency.

Once again, whenever you improve efficiency, when you save money, it's only the same thing as making money if you're already rich. If there are people who aren't rich enough to benefit from that, it just makes them poorer because they have less to do, and less ways to earn money. This is another potential huge increase in efficiency with enormous benefits. And the interesting question is where does it leave various kinds of people?

If we enter into the kind of world that Google likes, the world that Google wants, it's a world where information is copied so much on the Internet that nobody knows where it came from anymore, so there can't be any rights of authorship. However, you need a big search engine to even figure out what it is or find it. They want a lot of chaos that they can have an ability to undo.

It should be pointed out that the original design of the Internet didn't have even a copy function, because it originally just seemed stupid. If you have a network, why would you copy something? That's just inefficiency. I'm convinced the reason copying happened on the Internet was because Xerox PARC was so important as an early supporter of computers, that for Alan Kay to go to the Xerox people and say, "Oh, by the way, copying itself, even in the abstract will become obsolete because of computer networks", would have just blown their minds. We ended up with copying on a network.

But anyway, when you have copying on a network, you throw out information because you lose the provenance, and then you need a search engine to figure it out again. That's part of why Google can exist. Ah, the perversity of it all just gets to me.

If 3-D printers become good and ubiquitous, the number one question is going to be, can somebody make up an object and get paid for it? Just hypothetically, let's say 3-D printers are good enough to print out a new phone, which is conceivable, not immediately but it will happen, or to print out a new computer, a new tablet you'd want to use, or some other device. Is the company that operates the advertising auction system at the back end that's paying for the network connection the only party that makes money at that point? I don't think that's a sustainable future, and society would break before we hit that point, but right now what's funny is that is the path we're headed towards. When you're headed towards a path that's impossible, it means that something's going to break, and so you should get on a different path that's more plausible, and it's urgent that we find that other path.

The rise of 3-D printers could be particularly destabilizing in that it could hit economies that are reliant on particularly low-end manufacturing. It could be a disaster for China, and it could happen rather quickly. And at the same time, if you think about this: You have machines that can make machines… If people could get paid for creatively coming up with things for them to do, if you can make a living from that, from what you do with your heart and your head as regards to the creation of physical things…

Recycling is efficient suddenly because of the way this all happens. You can take old things and turn them into new things very efficiently, which you could do because just as you can have assembling robots and 3-D printers, you can also have disassembling, and de-printing robots.

In that world, you could have an incredible amount of employment, and generation of liberty and autonomy for people who are just helping things get creative, instead of the manufacturing paradigm where there’s a limited number of things that can be made.

Instead, they'll constantly be recycled, so there could be this entire churn, and all these new things. When this technology works, is this going to be a technology that just benefits whoever's auctioning off the advertising?

It can become such a bizarre system. What you have now is a system in which the Internet user becomes the product that is being sold to others, and what the product is, is the ability to be manipulated. It's an anti-liberty system, and I know that the rhetoric around it is very contrary to that. "Oh, no, there are useful ads, and it's increasing your choice space", and all that, but if you look at the kinds of ads that make the most money, they are tawdry, and if you look at what's happening to wealth distribution, the middle is going away, and just empirically, these ideals haven't delivered in actuality. I think the darker interpretation is the one that has more empirical evidence behind it at this point.

There's this question of why is there so much economic pain at once all over the world, what happened? There are a number of different explanations that can be helpful. Hitting some hard limits to growth in the world is part of it, the rise of new powers of India, and China, and Brazil, so that suddenly there are more people with means. That's part of the story. But there's something else going on here, too, which is that the mechanisms of finance just completely failed and screwed everybody. If we look at exactly what happened with the mortgage meltdowns and the utter failure of complex financial instruments in which securities were bundled in ways that were beyond human understanding, essentially, if you look at the extraordinary ways in which the whole world seemed to go into debt at once, what happened there?

There's a short answer to that question, which is finance got networked. The big kinds of computers that had made certain other industries efficient were applied to finance, and it broke finance. It made finance stupid. Let's back up a little bit.

The first example of computer networks really transforming an industry on a global scale did not come from a social networking site, or from search, or any of those Silicon Valley things, it was Wal-Mart. Wal-Mart pioneered the use of networking resources to make a global efficiency. Their supply chain was driven by real-time data, and extraordinary amounts of computation, and I had a window into their world because I had a consulting gig with them when they were doing it, and it was absolutely extraordinary.

Essentially what Wal-Mart recognized is that information is power, and by using network information, you could consolidate extraordinary power, and so have information about what could be made where, when, what could be moved where, when, who would buy what, when for how much? By coalescing all of that, and reducing the unknowns, they were able to globalize their point of view so they were no longer a local player, but they essentially became their own market, and that's what information can do. The use of networks can turn you from a local player in a larger system into your own global system. And all the people who succeed the best at using networks do precisely that. It's been done again and again. But Wal-Mart was in a way the pioneer.

If you want to, you can talk about the intelligence agencies as being the earlier pioneers, perhaps, but in a way Wal-Mart is the most impressive one, totally transformed the world. I'm not going to condemn them, because overall they brought so much good in their wake that it would be hard to condemn them. Consider that before Wal-Mart one of the greatest anxieties many of us had was the rise of China. What would that be like? Wal-Mart said, "Oh, the rise of China is going to be as a peaceful manufacturing partner." And China started to get rich, got happy, got nicer, and it just turned the rise of China into something that was so much better than anyone had foreseen, and Wal-Mart played a huge role in that. Without information systems there's no way that whole thing could have been coordinated to happen so quickly. That's an extraordinary good for everybody in the loop. You can't find a villain here and say, "This is the horrible thing", because a lot of these are complex and nuanced large-scale phenomena.

What Wal-Mart did with manufacturing, retail, the whole supply chain, and transportation preceded the consumer Internet, the general Internet. When the general Internet got good, Google had this idea of providing information services for free because the real money was in paid influence, or what they call advertising. I'm uncomfortable calling what Google does "advertising." In the history of capitalism, advertising has been a crucial component, whether we like it or not, because it romanticized human production. Without advertising, we wouldn't have had the rise of capitalism, as we know it. Many people can feel uncomfortable with that, they can find it manipulative, and they can find that it leads to waste and excess, that it's materialistic. There are all kinds of criticisms. But at any rate, whatever everyone's judgment is, advertising was indispensable to the rise of capitalism, and since I haven't seen any alternative that creates liberty for people better, I have to therefore respect it.

But Google's thing is not advertising because it's not a romanticizing operation. It doesn't involve expression. It's a link. It's just a little tiny minimalist link, and basically what they're selling is not advertising, they're not selling romance, they're not selling communication, what they're doing is selling access. What they're doing is they're saying, "You give us money, we give you access to these people, and then what you do with them is up to you." It's a gate keeping function. It's an arbiter of access. It's turning connections instead of being open into being paid. That's essentially what Google does. "We'll own the data, you'll pay for access to other people, but we'll give a whole ton of other stuff for free." And then it leads to this very strange schizophrenia, I'd say, where you think you're the user, but you're the used, or you're the product, and then you end up doing all this stuff to control your online presence, and your online reputation, and people become obsessed with that. But the real representation of you is the one you can't access, which is the one that's used to sell access to you to third parties. The whole thing is just, to my mind, increasingly perverse. And the real information about you isn't even separable. There's no dossier on you that you could get; it’s this correlative effect from all the other data that they have, this giant, proprietary correlative model of the world.

Anyway, back to Wal-Mart. With Wal-Mart, the consumer, or the ordinary person who was a shopper at Wal-Mart was confronted with these two pieces of news. One is, stuff they wanted to buy got cheaper, which of course is good, but the other thing is their own employment prospects were reduced, which is bad, and Wal-Mart's rhetoric sometimes try to balance these things and say, "We cost a lot people their jobs, and we also save people a lot of money", but the thing is you can't equate the two.

Once a particular party in a market has achieved a threshold where they have enough that they could lose, then saving becomes the equivalent of making, but if they haven't reached that threshold, saving is not the equivalent of making.

Wal-Mart created efficiencies, lowered costs, and yet overall made people poor, so it's a great example of efficiency often not being good for people, but it's all based on how you think about it. It's an interesting thing. Let's move forward to Silicon Valley. Silicon Valley has done the same thing. It's created efficiencies, but in a way that makes people poorer lately, and whether one likes this or not is a different question than whether it's even a sustainable path, and I would argue it simply isn't. We can't go on like this.

In the recent recession, what happened is that Wal-Mart's victories, its triumphs of using networking technology to make these global efficiencies were copied by the financial sector. Interestingly enough, this retailer was first. There were a few people in finance who were thinking about this and dabbling in it, but the big time came later, after Wal-Mart had demonstrated the principle.

I remember this well, because I also had a direct window on it, because they were recruiting. They were looking for quants to work on these things, so I knew a lot of the people who were starting to use major computation resources for finance in the early days of it, and coming up with schemes.

If you can collect all the information, you can find little things, you can find little differentials. I knew people who were moving money around banks around the world in weird cycles because they could take advantage of various slight differences in the times when they would close accounts, or weird little fluctuations. There were other people who were doing totally automated, statistical micro-fluctuation analysis to pull money out of a system, and all kinds of other schemes.

The interesting thing about this is that it completely defeats every argument for why a market should work, because there's no risk management. You can argue that there is, but empirically there isn't.

Essentially what happened with finance is a larger scale, albeit more abstract version of what happened with Wal-Mart, where a global system was optimized by being able to build data that could be concentrated locally using a computer network. It tremendously enriched the people who ran the network. It seemed to create savings for people initially who were the end users, the leafs of the network, very much as Google, or Groupon, seem to save them money initially. But then in the long-term it took away more from the income prospects of people than it could offer them in savings, very much as Wal-Mart did.

This is the pattern that we'll see repeated again and again as new applications of computer networks come up, unless we decide to monetize what people do with their hearts and brains. What we have to do to create liberty in the future is to monetize more and more instead of monetize less and less, and in particular we have to monetize more and more of what ordinary people do, unless we want to make them into wards of the state. That's the stark choice we have in the long-term.

In the case of the recent financial meltdowns, there are a couple of interesting features. One is the use of automation to avoid responsibility, and this is a phenomenon that you see again and again.

This has also happened in the American healthcare system. What you want to do is increase your rewards and reduce your risks. So you associate risk-taking behavior with an algorithm, or with some network effect, so it's very hard to personalize it when this happens. In a sense this is an inevitable correlate to saying that it's those who own the network who should benefit. If owning the network is the reason you benefit rather than decisions made on the network, then obviously it benefits the owners, but it also removes monetized roles from other people who are using the network. It's no longer choice that gets rewarded, or gets monetized. But then the flip side of that is that the risks which are taken are just dissipated to the world. We see this in healthcare.

I also had a wonderful window into the transformation of healthcare by computer networks because I had a consulting gig with some of the largest insurers as they were starting to make use of computer networks to improve their actuarial results. Once you can gather information in real time with a network, you can see so much more that the traditional idea of the insurer managing risk becomes absurd, because now you can say, "Well, I have enough information that it's not so much of a mystery what will happen, and what I want to do is just insure the people who won't need the insurance". Then you start breaking the whole system. Of course, this is exactly what happened in finance, as well, where the idea was to push all the risk onto others so that you, who run the network, are left with none of it.

The reason this breaks is that there's a local-global flip that happens. When you start to use an information network to concentrate information and therefore power, you benefit from a first arrival effect, and from some other common network effects that make it very hard for other people to come and grab your position. And this gets a little detailed, but it was very hard for somebody else to copy Wal-Mart once Wal-Mart had gathered all the information, because once they have the whole world aligned by the information in their server, they created essentially an expense or a risk for anybody to jump out of that system. That was very hard.

In a similar way, once you are a customer of Google's ad network, the moment that you stop bidding for your keyword, you're guaranteeing that your closest competitor will get it. It's no longer just, "Well, I don't know if I want this slot in the abstract, and who knows if a competitor or some entirely unrelated party will get it." Instead, you have to hold on to your ground because suddenly every decision becomes strategic for you, and immediately. It creates a new kind of glue, or a new kind of stickiness.

Exactly the same thing happens whenever somebody concentrates power using a big global network. And the thing about that is that you can rise to power so quickly in the way that something like Facebook rises quickly. The network effects can be so powerful that you cease being a local player.

An example of this is Wal-Mart removing so many jobs from their own customers that they start to lose profitability, and suddenly upscale players, like Target, are doing better. Wal-Mart impoverished its own customer base. Google is facing exactly the same issue long-term, although not yet. The finance industry kept on thinking they could eject waste out into the general system, but they became the system. You become global instead of local so that the system breaks. Insurance companies in America, by trying to only insure people who didn't need insurance, ejected risk into the general system away from themselves, but they became so big that they were no longer local players, and there wasn't some giant vastness to absorb this risk that they'd ejected, and so therefore the system breaks. You see this again and again and again. It's not sustainable.

If you aspire to use computer network power to become a global force through shaping the world instead of acting as a local player in an unfathomably large environment, when you make that global flip, you can no longer play the game of advantaging the design of the world to yourself and expect it to be sustainable. The great difficulty of becoming powerful and getting close to a computer network is: Can people learn to forego the temptations, the heroin-like rewards of being able to reform the world to your own advantage in order to instead make something sustainable?

It's not about Google, it's a general business idea which Google played a role in pioneering, but it's shared by Facebook, and also companies with which I am now affiliated through my work. It's not at all specific to Google at this point, but… People have to understand that there's no such thing as "free," that when they buy into a system in which they upload their videos to YouTube without expecting to make anything (unless they're very lucky to become a token Horatio Alger story) at the end of the day, or when they contribute to services like Google+, or Facebook, or other social networks, what's happening is they're working for the benefit of someone else's fortune by creating data that can be used to grant or deny access based on pay to these third parties, the tawdry third parties I mention so often.

There's a sense of, if you're adding to the network, do you expect anything back from it? And since we've been hypnotized in the last eleven or twelve years into thinking that we shouldn't expect anything for what we do with our hearts or our minds online, we think that our own contributions aren't worth money, very much like we think we shouldn't be paid for parenting, or we shouldn't be paid for raking our own yard. In those cases you are paid in a sense because there's still something that becomes part of you in your life, for all that you did.

But in this case we have this idea that we put all this stuff out there and what we get back are intangible or abstract benefits of reputation, or ego-boosting. Since we're used to that bargain, we're impoverished compared to the world that could have been and should have been when the Internet was initially conceived. The world that would create a strengthened middle class through what people do, by monetizing more and more instead of less and less. It's possible that that world could have never come about, but that was never tested. If we are absolutely convinced that this third way is impossible, and that we have to choose between "The Matrix" or Marx, if those are our only two choices, it makes the future dismal, and so I hope that a third way is possible, and I'm certainly going to do everything possible to try to push it.

We're not going to be able to test tomorrow because we've gone down this path so far that it will be a decade's long project to begin to explore it, but we must find our way back. I wouldn't be surprised if it's a century after Ted Nelson first proposed this thought in 1960 that this is how the Internet should be. It might be a century before we even start to seriously try to do it, but that's how things go sometimes in history. Sometimes it just takes a while to sort things out.

|

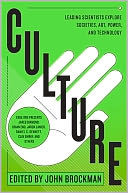

New Books From Edge

Future Science, edited by Max Brockman 18 original essays by the brightest young minds in science: Kevin P. Hand - Felix Warneken - William McEwan - Anthony Aguirre - Daniela Kaufer and Darlene Francis - Jon Kleinberg - Coren Apicella - Laurie R. Santos - Jennifer Jacquet - Kirsten Bomblies - Asif A. Ghazanfar - Naomi I. Eisenberger - Joshua Knobe - Fiery Cushman - Liane Young - Daniel Haun - Joan Y. Chiao "A fascinating and very readable summary of the latest thinking on human behaviour." — The Economist "Cool and thought-provoking material. ... so hip." — Washington Post The Best of Edge: Culture, edited by John Brockman 17 conversations and essays on art, society, power and technology: Daniel C. Dennett - Jared Diamond - Denis Dutton - Brian Eno - Stewart Brand - George Dyson - David Gelernter - Karl Sigmund - Jaron Lanier - Nicholas A. Christakis - Douglas Rushkoff - Evgeny Morozov - Clay Shirky - W. Brian Arthur - W. Daniel Hillis - Richard Foreman - Frank Schirrmacher The Best of Edge: The Mind, edited by John Brockman 18 conversations and essays on the brain, memory, personality and happiness: Steven Pinker - George Lakoff - Joseph LeDoux - Geoffrey Miller - Steven Rose - Frank Sulloway - V.S. Ramachandran - Nicholas Humphrey - Philip Zimbardo - Martin Seligman - Stanislas Dehaene - Simon Baron-Cohen - Robert Sapolsky - Alison Gopnik - David Lykken - Jonathan Haidt |