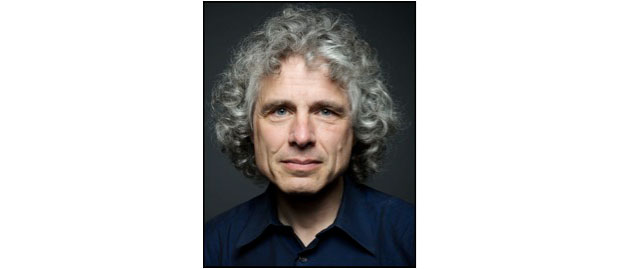

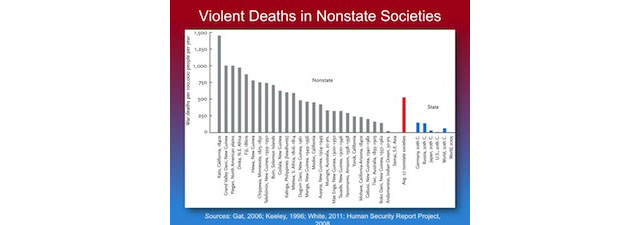

The other method of measuring violence in pre-state societies is ethnographic vital statistics. What is the rate of death by violence in people who have recently lived outside of state control, namely hunter-gatherers, hunter-horticulturalists, and other tribal groups?

There are 27 samples that I know of, where ethnographic demographers that have done the calculation. I've plotted them as war deaths per 100,000 people per year. They go as high as 1500, but the average across these 27 non-state societies is a little bit more than 500. Again, let's stack the deck against modernity by picking some of the most violent modern societies for comparison, such as, for example, Germany in the 20th century, with its two world war: its rate is around 135, compared to 524 for the non-state societies. Russia in the 20th century, with two world wars, a revolution, and a civil war, is about 130. Japan in the 20th century, about 30. United States in the 20th century, with two world wars plus five wars in Asia, is about a pixel.

Now, here is the world as a whole in the 20th century. This is another version of the figure that I alluded to earlier, which includes all the wars, genocides and man-made famines; it amounts to around 60. And this is the world in the first decade of the 21st century, which again is far shorter than one pixel.

So: not to put too fine a point on it, but when it comes to life in a state of nature, Hobbs was right, Rousseau was wrong.

What was the immediate cause? It was almost certainly the rise and expansion of states. Anyone who is familiar with world history knows about the various paxes—the pax Romana, pax Islamica, pax Hispanica, and so on. It's the historian's term for the phenomenon in which, when a state expands or an empire imposes hegemony over a territory, they try to stamp out tribal raiding and feuding. That is what drives the statistics down.

It's not that these early states had any benevolent interest in the welfare of their subjects, but rather, that tribal raiding and feuding is a nuisance to imperial overlords. For the same reason that a farmer will take steps to prevent its cattle from killing each other —it's a dead loss to the farmer—Imperial overlords tend to frown on tribal battles that just shuffle resources and destroy the tax base at a net loss to them.

The second major historical decline of violence can be captured in this woodcut of a typical day in the life in the Middle Ages. The decline has been called the "Civilizing Process."

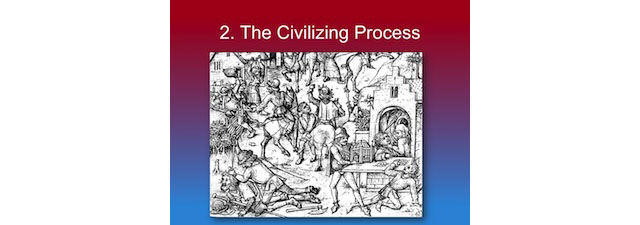

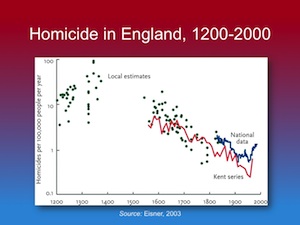

It's best illustrated by looking at homicide statistics, which go back in many parts of Europe to the 13th century. The historical criminologist Manual Eisner has assembled every estimate that he could find of homicide rates from records in England going back to about 1200.

I've plotted them here on a logarithmic scale, so that the scale goes from 100 homicides per 100,000 per year, to ten, to one, to a tenth of a homicide. And as you can see, there's an almost two order-of-magnitude decline in homicide from the Middle Ages to the present.

|

|

So a contemporary Englishman has about a 50-fold less chance of being murdered than his compatriot in the Middle Ages. (By the way, this high point here of 100 per 100,000 per year comes from Oxford.)

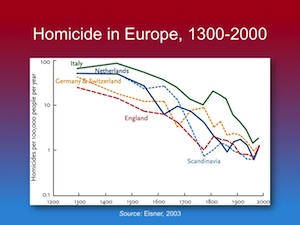

This is a phenomenon that is not restricted to England. It is true of every European country for which statistics are available. Again, here is a logarithmic scale, and the homicide rates goes from between ten and 100 down to a very narrow window of about one per 100,000 per year.

Here is an average of the five western European regions. And just to connect it to the previous historical development, I've plotted the non-state societies average up here, which is about 500 per 100,000 per year. (This gap is what I called the pacification process.) Then the civilizing process consists of this additional 30- to 50-fold reduction in the rate of homicide to the present.

The immediate cause was first identified by Norbert Elias in his classic book The Civilizing Process, from which I got the name for this development. In the transition from Middle Ages to modernity there was a consolidation of centralized states and kingdoms throughout Europe. Criminal justice was nationalized, and warlords, feuding, and brigandage were replaced by "the king's justice."

Simultaneously, there was a growing infrastructure of commerce: a development of the institutions of money and finance, and of technologies of transportation and time keeping. The result was to shift the incentive structure from zero-sum plunder to positive-sum trade.

The third historical decline of violence pertains to the fact that those first states, though they did bring down rates of feuding and vendetta and blood revenge, were rather nasty contraptions, which kept people in a state of awe with techniques such as breaking on the wheel, burning at the stake, sawing in half, impalement, and clawing. In a process that historians call the "Humanitarian Revolution", these forms of institutionalized violence were eventually abolished. The momentum for this movement was concentrated in the 18th century.

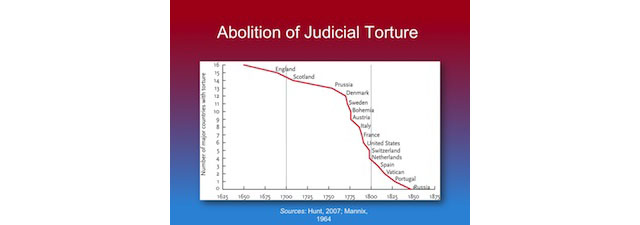

This graph shows the abolition of judicial torture (that is, torture as a form of punishment) in the major countries of the day, including the famous prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment by the 8th Amendment to the United States Constitution.

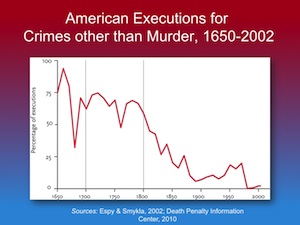

Also during this period there was a reduction in the use of the death penalty for non-lethal crimes. In 18th century England there were 222 capital offenses on the books, including poaching, counterfeiting, robbing a rabbit warren, being in the company of gypsies, and "strong evidence of malice in a child seven to 14 years of age." By 1861 the number of capital crimes was down to four.

Similarly, in the United States in the 17th and 18th centuries, the death penalty was prescribed and used for theft, sodomy, bestiality, adultery, witchcraft, concealing birth, slave revolt, counterfeiting, and horse theft. We have statistics for capital punishment in the United States since colonial times. As you can see, in the 17th century a majority of executions were for crimes other than homicide. In current times, the only crime that is punished by capital punishment other than homicide is conspiracy to commit homicide.

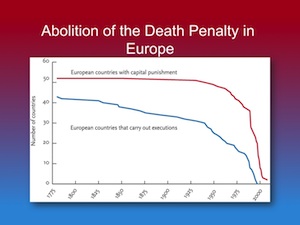

The death penalty itself, of course, has been abolished in most of Europe. Most of the abolitions were concentrated in the last fifty years. This is the number of European countries with capital punishment. Currently, only Russia and Belarus have it had on the books.

But interestingly, even before capital punishment was abolished by the stroke of a pen, it had fallen into disuse. You can see that the percentage of European countries that actually carry out executions has always been far lower, and the decline began much earlier.

Now the United States, of course, notoriously is the only Western democracy that has capital punishment (though only in two-thirds of the states), a number that has been dwindling. And to say that the United States has the death penalty is a bit of a fiction. If you look at the number of executions as a proportion of the population, it has been plunging since colonial times. Today, out of about 16,500 homicides per year, there are about 50 executions, and that rate has been in decline as well.

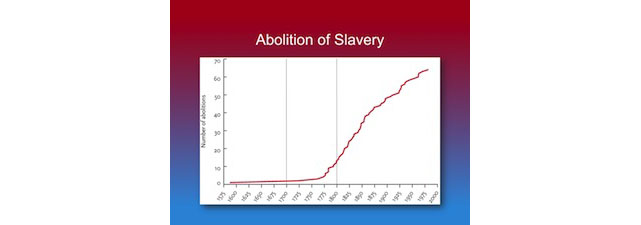

Other abolitions during the humanitarian revolution include witch hunts, religious persecution, dueling, blood sports, debtors prisons, and of course most famously, slavery.

This graph shows the cumulative number of countries that abolished slavery. For the first time in history, slavery is illegal everywhere in the world. The last countries to abolish it were Saudi Arabia in 1962, and Mauritania in 1980.

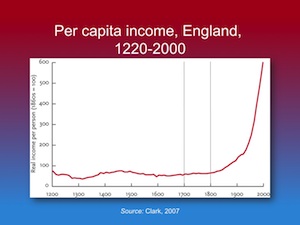

What were the immediate causes of the humanitarian revolution? A plausible first guess is affluence. One might surmise that as one's own life becomes more pleasant, one places a higher value on life in general. However, I don't think the timing works.

|

|

This is a graph of per capita income in England over the last 800 years. Most economic historians say that the world saw virtually no increase in affluence until the time of the Industrial Revolution starting in the early decades of the 19th century. But most of the reforms that I've been talking about were concentrated in the 18th century, when income growth was pretty much flat.

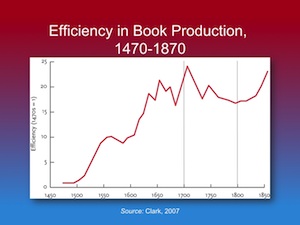

However, there is one technology that showed a precocious increase in productivity before the Industrial Revolution, and that was printing. Here's a graph showing the efficiency in book production, which increased 25-fold by 1700. The efficiency was put into use, and resulted in an exponential growth in the number of books published per year in England, France, and other western European countries.

And there were more literate people around to read them. By the 18th century a majority of men in England were literate.

Why should literacy matter? A number of the causes are summed up by the term "Enlightenment." For one thing, knowledge replaced superstition and ignorance: beliefs such as that Jews poisoned wells, heretics go to hell, witches cause crop failures, children are possessed, and Africans are brutish. As Voltaire said, "Those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities."

Also, literacy gives rise to cosmopolitanism. It is plausible that the reading of history, journalism, and fiction puts people into the habit of inhabiting other peoples' minds, which could increase empathy and therefore make cruelty less appealing. This is a point I'll return to later in the talk.

The fourth historical decline of violence has been called the "Long Peace." It speaks to the widespread belief that the 20th century was the most violent in history, which would seem to go against everything that I've said so far. Peculiarly, one never sees, in any of the claims that the 20th century was the most violent in history, any numbers from any century other than the 20th.

There's no question that there was a lot of violence in the 20th century. But take, for comparison, the so-called peaceful 19th century. That "peaceful" century had the Napoleonic wars, with four million deaths, one of the worst in history; the Taiping Rebellion in China, by far the worst civil war in history, with 20 million deaths; the worst war in American history, the Civil War; the reign of Shaka Zulu in southern Africa, resulting in one to two million deaths; the war of the Triple Alliance, which is probably the most destructive interstate war in history in terms of percentage of the population killed, namely 60 percent of Paraguay; the African slave raiding wars (no one has any idea what the death toll was); and of course, imperial wars in Africa, Asia and the South Pacific.

These remarks are all qualitative, meant to damp down the tendency to think that just because in Europe there was a span of several decades without war, that the world as a whole was peaceful in the 19th century as a whole.

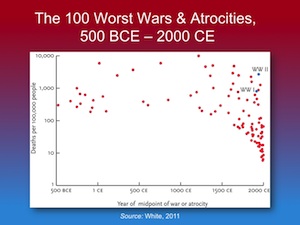

Now, it is undoubtedly true that the Second World War was the deadliest event in human history in terms of number of lives lost. But it's not so clear that it was the deadliest event in terms of percentage of the world population. Here is a graph that I've adapted from a forthcoming book by Matthew White entitled The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History's 100 Worst Atrocities. White calls himself an "atrocitologist." He tries to fit numbers to wars, genocides, and manmade famines throughout history.

Here we see 2500 years of human history, with White's top 100 atrocities, which I have scaled by the estimated size of the world population at the time. As you can see, World War II just barely makes the top ten. There are many events more deadly than World War I. And events which killed from a tenth of one percent of the population of the world to ten percent were pretty much evenly sprinkled over 2500 years of history.

Now this funnel-like concentration of points in the last few centuries does not mean that in ancient times they only committed big atrocities, whereas now we commit both big and little atrocities. It's rather an artifact of "historical myopia": the closer you get to the present, the more information you have. The smaller atrocities in the past were trees falling in the forest with no one to hear them, or not even deemed worthy of being written down.

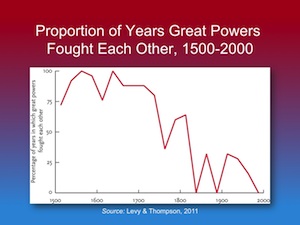

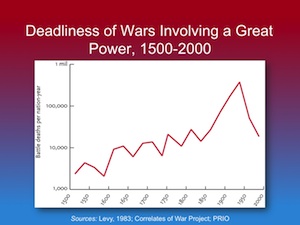

Let's zoom in now on the last 500 years. There is a data set from Jack Levy on trends in great power war. These are wars that involve the 800-pound gorillas of the day, that is the countries that can project military power outside their boundaries, which account for a disproportionate amount of the damage due to war (because wars fall along a power law distribution of damage).

The first graph shows the percentage of time that the great powers were at war. We see that five hundred years ago, the great powers were pretty much always at war with one another, and then the proportion of each quarter-century filled with great-power wars declined steadily. The next one shows the duration of wars involving the great powers—also a decline. Here is one that shows the number of great-power wars initiated per year, and that figure, too, declines steadily over the half-millennium.

But now we see a graph of the deadliness of war, which shows a trend that goes in the opposite direction—though wars involving great powers were fewer in number, they did more damage per country per year. Even that trend, though, did an about-face after 1950, when for the first time in modern history, great-power wars became simultaneously fewer in number, shorter in duration, and less deadly per unit time.

Now let’s zoom in on the last century, the 20th century. Here is a graph showing deaths in war all over the world, not just those involving the great powers. It shows that the increase in deadliness of war did indeed result in two horrific spikes of bloodletting centered on the two world wars. But since then there has been a long stretch without that degree of bloodletting. The fact that the 20th century comprises 100 years, not just 50 years, is one of the reasons why it's misleading to say that the 20th century was the most violent in history.

[QUESTION: Which population figures are you using to calculate rates of death in war?]

The denominator here is the world population, not the population size of countries involved in each war. There are arguments for doing it either way. The problem is that you can make the numbers go all over the place depending on the choice of the denominator, whether you choose the country that initiated the war, the collateral damage in other countries, the neighboring countries, and so on. So in all cases I've plotted deaths as a proportion of world population.

The extraordinary 65-year stretch since the end of the Second World War has been called the "Long Peace", and has perhaps the most striking statistics of all, zero. There were zero wars between the United States and the Soviet Union (the two superpowers of the era), contrary to every expert prediction. No nuclear weapon has been used in war since Nagasaki, again, confounding everyone's expectations. There have been no wars between any subset of the great powers since the end of the Korean War in 1953. There have been zero wars between Western European countries. The extraordinary thing about this fact is how un-extraordinary it sounds. If I say I'm going to predict that in my lifetime France and Germany will not go to war, everyone will say, "Yeah, yeah; of course they won't go to war." But that is an extraordinary statement when you consider that before 1945, Western European countries initiated two new wars per year for more than 600 years. That number has now stood at zero for 65 years.

And there have been zero wars between developed countries at all. We take it for granted nowadays that war is something that happens only in poor, primitive countries. That, too, is an extraordinary development; war used to be something that rich countries did, too. Europe, which traditionally has been the part of the world with the biggest military might, is no longer picking on countries in other parts of the world, or hurling artillery shells at one other with the rest of the world suffering collateral damage. This change has been extraordinary.

Now, what about the rest of the world? What has happened in the other continents while Europe has been racking up its peaceful zeros?

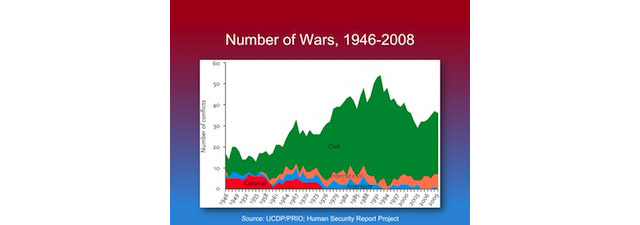

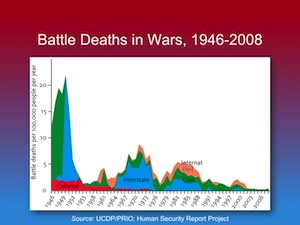

First let’s look at the number of wars. These graphs start at 1946 and they span the entire globe. I'll divide it into the different categories of war.

One kind of war has vanished off the face of the earth. The colonial war (red), which used to be quite destructive, no longer exists, because the European powers have given up their colonies. (This is, by the way, a stacked layer graph, so the relevant visual variable is the thickness of the layers.)

Here (blue) we see the fate of interstate wars, wars between two sovereign states. These have also been dwindling since the end of the Second World War. However, the number of civil wars—both pure civil wars within a country (green) and internationalized civil wars (orange), where some foreign country butts in, usually on the side of the government defending itself against an insurgency—increased until about 1990, and then has shown somewhat of a decrease as well.

So since 1946 there have been fewer wars between states, but there been more civil wars, mainly because newly independent states with inept governments were challenged by insurgent movements, and both sides were armed by the Cold War powers. But even civil wars declined after 1991 with the end of the Cold War and the stoking of these proxy wars by the superpowers.

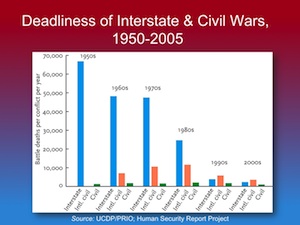

The crucial question now is: what kills more people, the fewer number of wars between countries, or the greater number of wars within countries? This graph shows the deadliness of interstate wars since the 1950s, that is, how many people are killed in a particular year of war. As you can see, the numbers has plummeted (I've already talked about that fact).

The tall blue bars represent deaths in interstate war, and as you can see they have plummeted over the decades. Much shorter are the internationalized civil wars (orange) and the civil wars (green). The fact that we have more civil wars and fewer interstate wars means that the total number of people has gone down, because the interstate wars of the past killed far more people than the civil wars of the present.

Now let's put the numbers back together, and instead of looking at the number of wars, look at number of deaths, again scaled by world population. This stacked-layer graph shows the number of people killed in wars since 1946. Here are the colonial wars (red). Here we see the number of people killed in interstate wars (blue), with spikes corresponding to the eras of the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Iran/Iraq War. These are the numbers of people killed in civil wars (green) and internationalized civil wars (orange).

The trajectory has been, to be sure, bumpy, but in the first decade of the 21st century, we are actually living in a time that even in comparison to recent decades is comparatively peaceable. In fact, one could almost say that the dream of the 1960s folk singers is coming true: the world is putting an end to war.

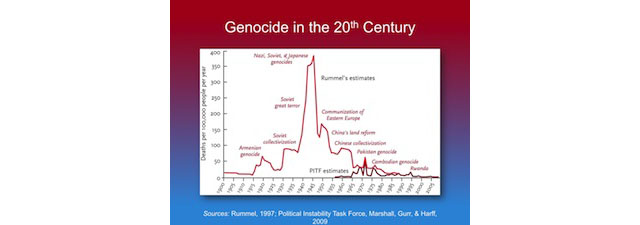

What about genocide? The last couple of graphs plot what are called "state-based conflicts, where you have two organized armed forces fighting, at least one of which is a government. What about cases in which governments kill their own citizens? Again, there's a cliché that the 20th century was the Age of Genocide. But the claim is never made with any systemic comparison of previous centuries.

Historians who have tried to track genocide over the centuries are unanimous that the notion that the 20th was "a century of genocide" is a myth. Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn, their The History and Sociology of Genocide, write on page one, "Genocide has been practiced in all regions of the world and during all periods in history."

What did change during the 20th century was that for the first time people started to care about genocide. It's the century in which the word "genocide" was coined and in which, for the first time, genocide was considered a bad thing, something to be denied instead of boasted about.

As Chalk and Jonassohn say of ancient histories, "We know that empires have disappeared and that cities were destroyed, and we suspect that some wars were genocidal in their results. But we do not know what happened to the bulk of the populations involved in these events. Their fate was simply too unimportant. When they were mentioned at all, they were usually lumped together with the herds of ox and sheep and other livestock."

To give some examples: if Old Testament history were taken literally, there were genocides on almost every page; the Amalakites, Amarites, Canaanites, Hivites, Hitites, Jevasites, Midianites, Parazites and many other. Also, genocides were committed by the Athenians in Melos; by the Romans in Carthage; and during the Mongol invasions, the Crusades, the European wars of religion, and the colonization of the Americas, Africa and Australia.

We have something even resembling numbers only for the 20th century. But if we plot those numbers, they refute the impression that the massacres in Bosnia, Rwanda and Darfur are indications that nothing has changed, that the world has learned nothing since the Holocaust. This graph shows the best estimates that we can find of rates of death in genocide. Is certainly true that there was a burst of genocides from the 1930s to the early '50s in Europe, and from the '20s through the '70s in Asia. But the trend since World War II has been downward. It is definitely not the case that "nothing has changed" since the era of the Second World War. Even with the Rwanda genocide, a small proportion of the world’s population, compared to earlier decades, is massacred by their governments.

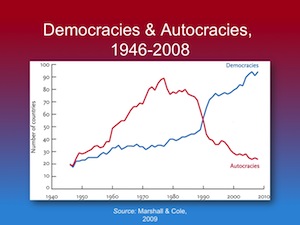

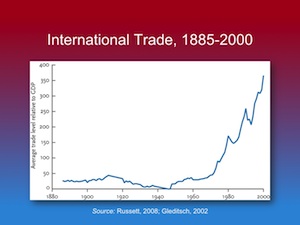

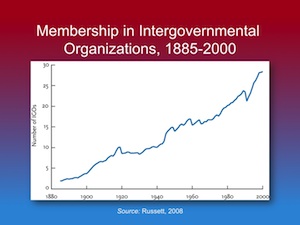

So what are the immediate causes of the Long Peace, and what I call the new peace (that is, the Post-Cold War era)? They were anticipated by Immanuel Kant in his remarkable essay, "Perpetual Peace" from 1795, in which he suggested that democracy, trade and an international community were pacifying forces. The hypothesis has been taken up again by a pair of political scientists, Bruce Russett and John Oneal, who have shown that all three forces increased in the second half of the 20th century. In a set of regression analyses, they showed that all of them are statistical predictors of peace, holding everything else constant.

|

|

|

|

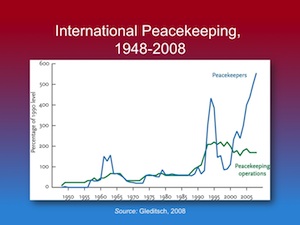

Specifically, the number of democracies has increased since the Second World War, and again since the end of the Cold War, relative to the number of autocracies. There's been a steady increase in international trade since the end of the Second World War. There's been a continuous increase in the number of intergovernmental organizations that countries have entered into. And especially since the end of the Cold War in 1990, there's been an increase in the number of international peace-keeping missions, and even more importantly, the number of international peace keepers that have kept themselves in between warring nations mostly in the developing world.

The final historical development I call the Rights Revolutions. This is the reduction of systemic violence at smaller scales against vulnerable populations such as racial minorities, women, children, homosexuals and animals.

|

|

|

|

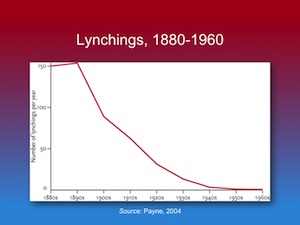

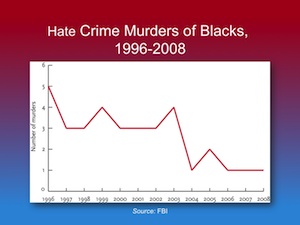

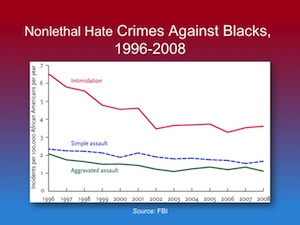

The civil rights revolution saw a reduction in the once socially-sanctioned practice of lynching. There used to be 150 lynchings per year in the United States, over the course of the 20th century the number has gone down to zero. Hate crime murders of blacks, which started to be recorded in the mid-1990s, went down from the single digits to one per year. Non-lethal hate crimes such as intimidation and assault have also been in decline since they were first measured.

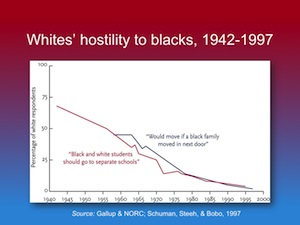

Also, the kinds of racist attitudes that encourage violence against minorities, such as the percentage of Americans saying that they would move if a black family moved in next door, or believe that black and white students should go to separate schools, has now fallen into the noise—the range of crank opinion—and is basically indistinguishable from zero.

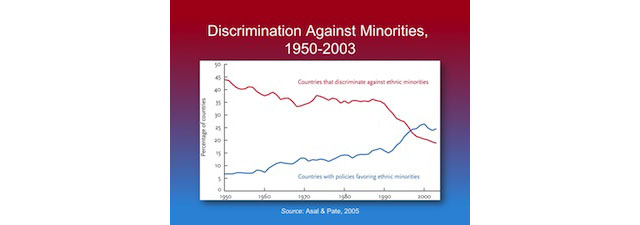

This is a trend that has taken place not just in the United States, but worldwide. The number of countries that have laws on the books that discriminate against ethnic, religious, or racial minorities has been in steady decline. In fact, the number of countries that have tried to tilt the scale in the other direction with affirmative action and remedial discrimination policies has increased. So now more countries in the world discriminate in favor of disadvantaged minorities than discriminate against them.

|

|

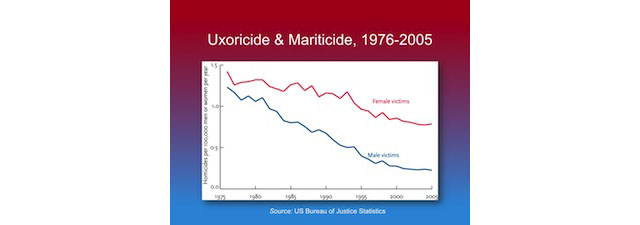

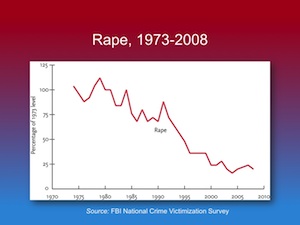

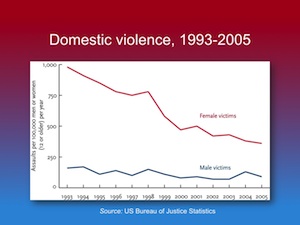

The women's rights movement has seen an 80 percent reduction in rape since the early '70s when it was put on the agenda as a feminist issue. There has also been a two-thirds decline in domestic violence, spousal abuse, or wife beating, and a 50 percent decline in husband beating. In the most extreme form of domestic violence, namely uxoricide and matricide, there's been a decline both in the number of wives that are murdered by their husband's and the number of husbands that have been murdered by their wives. In fact, the decrease is much more dramatic for husbands. Feminism has been very good to men, who are now much more likely to survive a marriage without getting murdered by their wives.

|

|

|

|

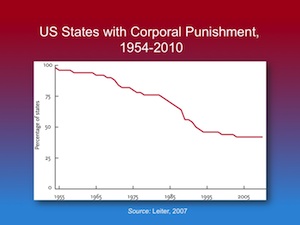

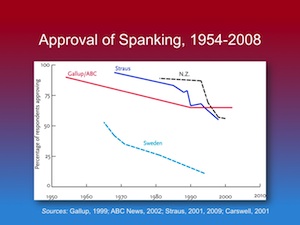

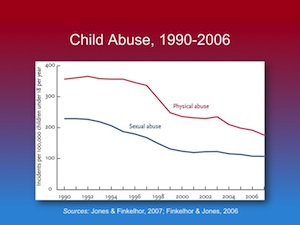

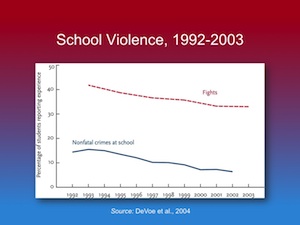

The children's rights movement has seen a decline in the United States of the number of states that permit corporal punishment in schools, such as "paddling" and "hiding." In much of Europe, it's been abolished outright. But even in the United States, it's been in decline. The approval of spanking and the implementation of spanking have been in decline in every country in which they have been measured. Here are data from the United States, New Zealand and Sweden. In fact, spanking, even by parents, is illegal in many European countries now. Child abuse, too, has been in decline since statistics were recorded in the early 1990s. And violence in schools, such as fighting and bullying, has been in decline.

|

|

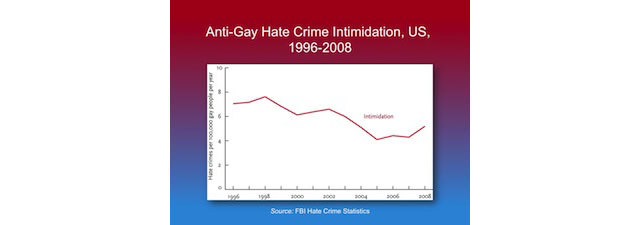

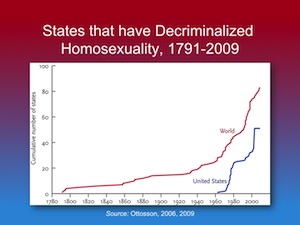

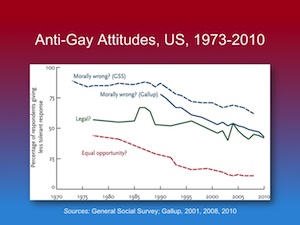

The gay rights movement has seen an increase in the number of states in the world, and American states, that have decriminalized homosexuality (it used to be a felony). Anti-gay attitudes have been in steady decline, such as whether homosexuality is "morally wrong," whether it should be made illegal, and whether gay people should be denied equal opportunity. Hate crimes of intimidation against gays have been in decline since they were first measured.

|

|

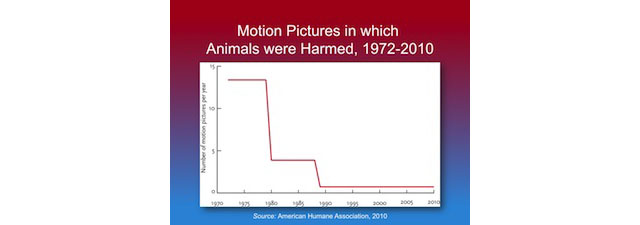

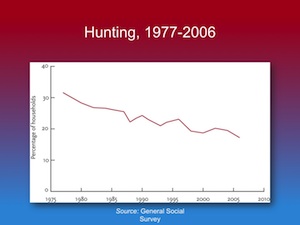

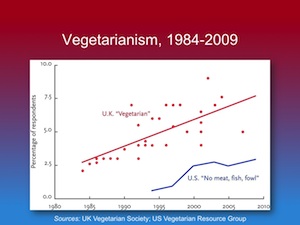

The animal rights movement has seen a decline in hunting, an increase in vegetarianism, and a decrease in the number of motion pictures in which animals have been harmed.

The key question now is: Why has violence declined over so many different scales of time and magnitude? One possibility is that human nature has changed, and that people have lost their inclinations towards violence. I consider this to be unlikely. For one thing, people continue to take enormous pleasure, and allocate a lot of their disposable income, to consuming simulated violence, such as in murder mysteries, Greek tragedy, Shakespearean dramas, Mel Gibson movies, video games and hockey.

But perhaps more to the point are studies of homicidal fantasies, which ask people the following question: "Have you ever fantasized about killing someone you don't like?" When you ask that question of a demographic with a very low rate of actual violence, namely American university students, you find that about 15 percent of the women and a third of the men frequently fantasize about killing people they don't like; and more than 60 percent of women and three-quarters of men at least occasionally fantasize about killing people they don't like. (And the rest of them are lying—or at least might sympathize with Clarence Darrow when he said, "I've never killed a man, but I've taken great pleasure in reading many obituaries."

A more likely possibility is that human nature comprises inclinations toward violence and inclinations that counteract them—what Abraham Lincoln called the "better angels of our nature." Historical circumstances have increasingly favored these peaceable inclinations.

What are the parts of human nature that militate toward violence? I count five, depending on how you lump or split them.

There's raw exploitation, that is, seeking something that you want where a living thing happens to be in the way; examples include rape, plunder, conquest, and the elimination of rivals. There’s nothing particularly fancy in the psychology of this kind of violence other than a zeroing out of whatever inclinations would inhibit us from that kind of exploitation.

There's the drive toward dominance, both the competition among individuals to be alpha male, and the competition among groups for ethnic, racial, national or religious supremacy or pre-eminence.

There's the thirst for revenge, the kind of moralistic violence that inspires vendettas, rough justice, and cruel punishments.

And then there's ideology which might be the biggest contributor of all (such as in militant religions, nationalism, fascism, Nazism, and communism), leading to large-scale violence via a pernicious cost- benefit analysis. What these ideologies have in common is that they posit a utopia that is infinitely good for infinitely long. You do the math: if the ends are infinitely good, then the means can be arbitrarily violent and you're still on the positive side of the moral ledger. Also, what do you do with people who learn about an infinitely perfect world nonetheless oppose it? Well, they are arbitrarily evil, and deserve arbitrarily severe punishment.

Now let's turn to the brighter side, our so-called better angels.

They include the faculty of self-control: the ability to anticipate the consequences of behavior, and inhibit violent impulses. There’s the faculty of empathy (more technically, sympathy), the ability to feel others' pain. There’s the moral sense, which comprise a variety of intuitions including tribalism, authority, purity, and fairness. The moral sense actually goes in both directions: it can push people to be more violent or less violent, depending on how it is deployed. And then there is reason, the cognitive faculties that allow us to engage in objective, detached analysis.

Now we face the crucial question: Which historical developments bring out our better angels? I'm going to suggest there are four.

The first implies that Hobbes got it right: a Leviathan, namely a state and justice system with a monopoly on legitimate use of violence, can reduce aggregate violence by eliminating the incentives for exploitative attack; by reducing the need for deterrence and vengeance (because Leviathan is going to deter your enemies so you don't have to), and by circumventing self-serving biases. One of the major discoveries of social and evolutionary psychology in the past several decades is that people tend to exaggerate their adversary's malevolence and exaggerate their own innocence. Self-serving biases can stoke cycles of revenge when you have two sides, each of them intoxicated with their own sense of rectitude and moral infallibility.

Historical evidence that the Leviathan is a major pacifying force includes the first two historical developments that I spoke of, namely the Pacifying and Civilizing Processes, both of which were consequences of the rise of states. Also the fact that reversals in the trends, where violence re-erupts, tend to take place in zones of anarchy, like the American Wild West, failed states, collapsed empires, and mafias and street gangs that deal in contraband (so they can't call in the court system to enforce their interests in business disputes but have to resort to intimidation and revenge). A final kind of evidence is the demonstrable effectiveness of international peace-keepers, who use a kind of soft power on the international stage to keep warring parties apart.

The second pacifying force is identified by the theory of "Gentle Commerce." Plunder is a zero-sum or even a negative sum game: the victors' gain is the loser's loss. Trade, in contrast, is a positive-sum game. (We will hear more from both Leda and Martin that reciprocal altruism, such as gains in trade, can result in both sides being better off after an interaction.) Over the course of history, improvements in technology have allowed goods and ideas to be traded over longer distances, among larger groups of people, and at lower cost, all of which change the incentive structure so that other people become more valuable alive than dead. To be concrete: I doubt that the United States is going to declare war on China (though there's much that we don't like about that country), because they make all our stuff. And I doubt China will declare war on us, because we owe them too much money.

Some historical evidence comes from statistical studies showing that countries with open economies and greater international trade are less likely to engage in war, are less likely to host civil wars, and have genocides.

A third pacifying force is what Peter Singer called the "Expanding Circle," although Charles Darwin in first stated the idea in The Descent of Man. According to this theory, evolution bequeathed us with a sense of empathy. That's the good news; the bad news is that by default, we apply it only to a narrow circle of allies and family. But over history, one can see the circle of empathy expanding: from the village to the clan to the tribe to the nation to more recently to other races, both sexes, children, and even other species.

This just begs the question of what expanded the circle. I think one can argue that the forces of cosmopolitanism pushed it outward: exposure to history, literature, media, journalism, and travel encourages people to adopt the perspective of a real or fictitious other person. Experiments by Daniel Batson and others have shown that reading a person’s words indeed leads to an increase in empathy, not just for that person, but also for the category that the person represents.

Historical evidence includes the timing of the Humanitarian Revolution of the 18th century, which was preceded by the Republic of Letters, the great increase in written discourse. Similarly, the Long Peace and Rights Revolutions in the second half of the 20th century were simultaneous with the "electronic global village." And perhaps—this is highly speculative—but it's often been stated that the rise of the Internet and of social media might have been behind the color revolutions and the Arab Spring of the 21st century.

I think the final and perhaps the most profound pacifying force is an "escalator of reason." As literacy, education, and the intensity of public discourse increase, people are encouraged to think more abstractly and more universally, and that will inevitably push in the direction of a reduction of violence. People will be tempted to rise above their parochial vantage point, making it harder to privilege their own interests over others. Reason leads to the replacement of a morality based on tribalism, authority and puritanism with a morality based on fairness and universal rules. And it encourages people to recognize the futility of cycles of violence, and to see violence as a problem to be solved rather than as a contest to be won.

What's the evidence for reason being a pacifying force which has helped to propel the decline of violence? We do know that abstract reasoning abilities (as measured by the most abstract components of an IQ test) have increased in the 20th century. The so-called Flynn Effect consists of an increase of about three IQ points per decade since the beginning of the 20th century, and the gains have been concentrated not in factual knowledge such as vocabulary and information, but rather, in abstract reasoning (such as in Similarities questions, like "What do an egg and a seed have in common?" and "What do an inch and a pound have in common.")

It's been shown that people (both at the level of individuals and of entire societies) who have higher levels of education and measured intelligence commit fewer violent crimes, cooperate more in experimental games (we'll hear today from Martin Nowak and Leda Cosmides about these games), have more classically-liberal attitudes, are less likely to be racist, sexist, xenophobic, homophobic, and are more receptive to democracy.

Whatever the causes of the decline of violence, it has profound implications. One of them is it calls for a reorientation of our efforts toward violence reduction from a moralistic mindset to an empirical mindset. It leads us to ask not just the question "Why is there war?" but, what might be a better question, "Why is there peace?" Not just "What are we doing wrong?" but "What have we been doing right?" Because we have been doing something right, and it seems to me that's it’s important to understand what it is.

In addition, the decline of violence has implications for our assessment of modernity: the centuries-long erosion of family, tribe, tradition and religion by the forces of individualism, cosmopolitanism, reason and science.

Now, everyone acknowledges that modernity has given us longer and healthier lives, less ignorance and superstition, and richer experiences. But there is a widespread romantic movement which questions the price. Is it really worth it to have a few years of better health if the price is muggings, terrorism, holocausts, world wars, gulags, and nuclear weapons?

I argue that despite impressions, the long-term trend, though certainly halting and incomplete, is that violence of all kinds is decreasing. This calls for a rehabilitation of a concept of modernity and progress, and for a sense of gratitude for the institutions of civilization and enlightenment that have made it possible.

Q & A

BENEDICT CAREY: You mentioned at the beginning that there's no guarantee that this will continue. What are some of the things that you think are most likely to upset the trend and bump it up again?

STEVEN PINKER: One is the "unknown unknowns", to quote Donald Rumsfeld. Things that could come out of the blue. Some fanatical dictator under the sway of a new ideology festering somewhere in the world who will gather supporters, take over a country, and decide that it's a good idea to re-conquer the neighbors. That kind of thing can happen. We don't know where, we don't know when, and it's unwise to predict that current trends will continue smoothly.

It's also possible that some fanatic who gets his hands on a stray nuclear weapon could send the statistics skyward. One guy or one radical cell or one group could do a lot of damage. It’s then almost a philosophical question whether this would constitute a counterexample to the world becoming less violent. No one else might think that the violence is a good idea, but one person or small groups could rack up big numbers.

It's also conceivable that climate change will cause a struggle over land or water. I might add that that is not a given. Studies that have tried to correlate resource scarcity and climate shocks at Time 1 with violence at Time 2 (everything else held constant) have found virtually no correlation. Famines can cause a lot of misery, and they can sometimes cause local skirmishes over watering holes, but in general, they don't lead to wars, because wars require the decision of some organized government or militia, whose leaders may not care about whether the population are starving or not in the calculations that lead them to declare war.

The United States, for example, during the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression, didn't have a civil war. The civil war that we did have was over quite another matter.

NICHOLAS PRITZKER: I've heard, probably on bad authority and a small sampling, that there's no evidence of violence among Cro-Magnon populations. Is there any proof to that rumor?

STEVEN PINKER: We don't have enough skeletons to know. There's some indirect evidence that violence goes back earlier than Cro-Magnon. For one thing, depending on how you interpret the evolutionary continuity, common chimpanzees engage in what we would call genocide if it occurred among humans—perhaps we should call it chimpicide—and probably the common ancestor of humans and chimps did as well.

There is evidence for violent trauma and cannibalism in Homo heidelbergensis, which is close to the common ancestor of Neanderthals and sapiens. Also, in our genome, there are genes that defend us against the prion diseases that are transmitted through cannibalism, suggesting that cannibalism goes back several hundred thousand years. And the fact that we're a sexually dimorphic species, with the males bigger than the females, which you tend to find, on average, in species that have more violent male/male competition. All of this is indirect evidence that say that violence goes back a long way.

And while I think you're right that there's no direct evidence of violence in Cro-Magnon, there are cave paintings showing war, though the oldest that we know of is from about 6,000 years ago.

STEWART BRAND: I imagine there are some people that are quite offended by your thesis. I'm wondering, whom are you hearing from and what are you hearing?

STEVEN PINKER: There are a number of people for whom this is an unwelcome message. Activists of various kinds don't like to hear good news because, by their reckoning, it encourages complacency: "Oh, so you’re saying the world is okay. Then why bother stamping out human trafficking?" and so on. I actually think they're mistaken even in the practical implications. It's much more likely that people reading about nothing but horrific events, say in Africa, would write off the whole continent as a hell hole. "Why throw money into a snake pit? Maybe they were better off when they were colonized, and independence was a bad idea." The fact that some peace-building measures actually work, I argue, is more of a reason to put effort and money into Africa. I think good news will actually encourage the right kinds of activism, rather than discourage them.

On the other side is a kind of conservative romanticism about pre-modernity: the Enlightenment was a terrible mistake, things were better when people had the moral clarity of church and family and community. This communitarian romanticism has both right-wing and left-wing flavors: religious romanticism and green romanticism.

Then there is an Americocentric theory of world history that says that everything bad happening in the world can be attributed to the actions of the United States. In that vaguely Chomskyan theory of politics, if you say that there's anything good about western civilization, that's considered reactionary.

Finally, there’s a belief among many anarchists and radical libertarians who that all evil is caused by the state. To them, Leviathan theories are highly offensive.

DANIEL KAHNEMAN: I'm just curious whether you see a decline in the ability to dehumanize categories of people? If we look at genocides in the 20th century, Nazi Germany, Srebrenica, you get people who are fairly normal in every way and they can become convinced that there is no difference between other people and animals. And it happens, clearly, can be made to happen, intelligence is no defense against it; literacy is no defense against it. And what are the forces do you think that...

STEVEN PINKER: I would put it the other way around. The default probably is that you do dehumanize out of your small circle, and what we are seeing are the remaining pockets of default dehumanization, or of backsliding.

There are two mindsets that allow these atrocities to happen. One is dehumanizing, where you consider other groups of people less than human. Then there's demonizing, where you consider them to be fully human, which makes them all the more contemptible because of the evil choices that they've made. Daniel Goldhagen has set up a 2 X 2 taxonomy of genocides according to whether the victims were demonized, de-humanized, or both.

For example, well before the 20th century one sees descriptions of Native Americans by settlers, colonists, and governments that use the metaphor of vermin. When it was asked, for example, after various massacres, "Why kill all the children, if it's just the warriors that have been harassing you; why kill the babies?," the answer, independently offered by a number of colonists was, "If you want to get rid of the lice you have to kill the nits." This is the same language that was used by Oliver Cromwell in his genocides during the re-conquest of Ireland.

I do agree that literacy, and certainly intellectualism, are not guarantees against a dehumanizing mindset, but they are probably statistical forces that push against it. Cosmopolitanism, including reading accounts of what it's like to be a Native American or a Vietnamese peasant, are likely to reduce the probability of de-humanization. But it is a tendency we naturally backslide into.

JARON LANIER: I'd like to hypothesize one civilizing force, which is the perception of multiple overlapping hierarchies of status. I've observed this to be helpful in work dealing with rehabilitating gang members in Oakland. When there are multiple overlapping hierarchies of status there is more of a chance of people not fighting their superior within the status chain. And the more severe the imposition of the single hierarchy in people's lives, the more likely they are to engage in conflict with one another. Part of America's success is the confusion factor of understanding how to assess somebody's status.

STEVEN PINKER: That's a profound observation. There are studies showing that violence is more common when people are confined to one pecking order, and all of their social worth depends on where they are in that hierarchy, whereas if they belong to multiple overlapping groups, they can always seek affirmations of worth elsewhere. For example, if I do something stupid when I'm driving, and someone gives me the finger and calls me an asshole, it's not the end of the world: I think to myself, I’m a tenured professor at Harvard. On the other hand, if status among men in the street was my only source of worth in life, I might have road rage and pull out a gun.

Modernity comprises a lot of things, and it's hard to tease them apart. But I suspect that when you're not confined to a village or a clan, and you can seek your fortunes in a wide world, that is a pacifying force for exactly that reason. Also, projecting upward to the way we intellectualize our affairs, an interesting development over the 20th century is the concept that you can be, say, Jewish and American, and this is not a conflict. You can be Italian-American, and the hyphen doesn't compromise either identity.

We take it for granted that we may have loyalties that go in different directions, but it's surprising how recent this appreciation is. There's a quote from that great "progressive" president Woodrow Wilson (who kin fact purged the federal government of black employees, and re-segregated Princeton when he was president of the university). He said, "Any American who carries around a hyphen is wielding a dagger aimed at the heart of the republic." It seems Neanderthal today, but he obviously was a smart man, and it made sense to him and to other people at the time. Today we think, "Well, you go to Knights of Columbus and that's the Italian part, and you salute the flag and that's the American part, and what's the big deal? These are two overlapping polities that we belong to." But that involves some cognitive sophistication. The default is to essentialize people, and you can't have two essences—it's not an essence if there are two of them. And so this style of abstract thinking with overlapping matrices may be part of the Flynn-effect driven increase in tolerance and classical liberalism.

LEDA COSMIDES: I was wondering two things. One is very odd. You were talking about dehumanization, and there's starting to be evidence that people who frame things more in terms of in-group and out-group have more outward fear, and also have a greater perceived vulnerability to disease. They feel that they're more vulnerable to disease and since you're living in close contact with your family and friends, you already have their germs. But the people who you're most likely to catch diseases from are people from other groups.

I was wondering, in looking at these trends, if you're seeing any trends in decline in the fear of groups and the kinds of war that can go along with increases in public health that would decrease people's perceived vulnerability to disease?

STEVEN PINKER: Randy Thornhill claims that there is such a correlation.

LEDA COSMIDES: Well, it's not just Randy. There have been more and more people who are finding that kind of link between pathogen fears and ingroup-outgroup psychology.

STEVEN PINKER: It's certainly possible. I suspect that it's more driven cognitively by who you naturally categorize as on the outside of your circle of group identity. But it's possible that the size of that circle is driven by some kind of fear of contamination.

LEDA COSMIDES: Right, I think that's the claim. But the real question I had was about the cosmopolitanism, because I'm puzzled by that in a certain sense. It almost sounds, like "come be an undergraduate and everything is going to be okay." I'm wondering if that is a real factor that's contributing to this. It must be driven a lot by popular culture because you don't have massive numbers of people reading Proust and etc.

STEVEN PINKER: It's a rising tide that lifts all the boats. It sounds elitist to say this, but attitudes toward women, homosexuals, and racial minorities, and the tolerant attitudes that we celebrate of not beating up your kids, tend to start among the most educated strata, and you can see the rest of the country being dragged behind. With a lot of these statistics, the red states today have attitudes that the blue states had 30 years ago—toward women, towards spanking, towards homosexuals, towards animal rights, and so on.

What starts out at the universities and the pundits can trickle down and become conventional wisdom. That probably happens worldwide as well. This is another thing I'll probably get flak for saying, but very roughly you can see a continuum in the world in a lot of variables related to the decline of violence: Western Europe, then the American blue states, then the American red states, then Latin America and Asian democracies, and the Islamic world and Africa pulling up the rear. We can look, say, at the criminalization of homosexuality in Africa, or human trafficking, and say the world is in a terrible state, which of course it is. But the historical trend is that the other parts of the world eventually catch up. Slavery is a concrete example: just fifty years ago, slavery was still legal in Saudi Arabia.

LEDA COSMIDES: But that's the legal part. I thought there was, quantitatively, an increase in slavery, alarming increase in slavery recently.

STEVEN PINKER: No, I don't think there is. For one thing, human trafficking can't be compared to African slavery in terms of the death rate, the suffering inflicted on the people, or the amount of time that it lasts in a person's life. And even human trafficking involves a fraction of the percentage of people that used to be slaves when slavery was legal and ubiquitous. Probably there have been centuries in the past in which the majority of the world's population could be classified as slaves. What you're seeing here is a common dynamic: there's a sudden increase in concern, which looks like an increase in incidence. We care about it now. Fifty years ago people didn’t.

GEORGE DYSON: A question about when you speak to nuclear weaponeers they like to take a lot of credit. They'll say, look what we did may have been bad, but look, we had no major war. They like to take your graph and make a very different conclusion and take the credit for it. Do you think they're taking more credit than they deserve?

STEVEN PINKER: Yes. Someone else [Elspeth Rostow] proposed that the nuclear bomb be given the Nobel Peace Prize! But I suspect not. For one thing, if you actually check to see whether the distribution of nuclear weapons predicts peace through deterrence, it rarely, if ever, does. For example, the Soviet Union established its hegemony over Eastern Europe in exactly the era in which the United States was a nuclear monopoly, the late 1940s. You also find lots of cases where a non-nuclear power challenged a nuclear power, like Argentina challenging Britain in the Falklands, Egypt challenging Israel in 1973, many countries challenging the United States, colonial Algeria seceding from France, and so forth.

There are two reasons that nuclear weapons probably haven’t been a critical factor. Since 1962, but probably growing before that, there has been a "nuclear taboo," the idea that nuclear weapons live in a sphere of hypotheticals, that you use them to defend yourself against an existential threat but in actual battlefield calculations it's not a live option. The last time it was breathed as a live option was when Barry Goldwater mused that there was no reason not to use tactical nuclear weapons in Vietnam, which led to the "Daisy" ad, and to Lyndon Johnson winning the biggest landslide in electoral history.

Nuclear weapons, paradoxically, are so militarily useless that they haven't really affected balance of power considerations. This is not to deny that deterrence has been important, just that the massive amount of destruction that countries like the U.S. and the USSR could inflict with conventional weaponry made each very nervous about the other even if neither side had had nuclear weapons. World War II in Europe didn't involve nuclear weapons, but was a kind of destruction that no one wanted to see again. The theory of the Nuclear Peace is quite popular, but I’m skeptical.

GEORGE DYSON: It's important for you to say that.

JENNIFER JACQUET: Do you think it's possible that we've shifted the violence toward one another toward other life forms? Especially through mechanization—the idea that now we have factory farming and industrial fishing and things like that.

STEVEN PINKER: I suspect not. Cruelty and indifference to animals go back probably as far as our species goes back. What has changed is efficiency — we can scoop up fish faster than we used to —and certain changes in habits. Starting in the '60s, people got the idea that white meat is healthier than red meat. But if you switch your meat from beef to poultry, you need 200 chickens to provide the same amount of meat as one cow. That creates the demand for a vastly larger number of sentient lives to be brought into being and snuffed out to meet the same demand. People are no crueler; they just have come to prefer white meat and until recently have been indifferent to the source of their dinner. There's been a constant level of callousness and indifference, but there's been an increase in industrial efficiency.

Now, of course, there's also, for the first time in the West, a widespread concern about the welfare of the animals that gave their lives for our dinner. You see both an increase in vegetarianism, an increase in the number of laws passed that protect the rights of farm animals, and an increase in the efforts by the industrial farmers to at least project an image of caring for animals, which probably has led to improvements in their welfare.

There are still enormous unrealized gains to be made in reducing cruelty. But the historical direction is we care more rather than less, even if below people’s radar a lot more bad things were happening

MICHAEL GAZZANIGA: Everybody's always worried about the coming uptick in violence. Last week the Supreme Court tossed out this case Brown versus the gaming industry in violence, a seven to two decision. The minority opinion was written by Justice Breyer, who is generally viewed as the science judge. He goes into a long discussion, 50 references, about how it is demonstrated that watching violent games, video game playing, and so forth, leads to much greater violence in children, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. And so therefore, this is so bad that it should trump fee speech aspects of the issue.

Do you have any thoughts on that? The things that the culture is doing, are there things out there boiling out around that may change this calculation? That may increase people's tendency toward violence for solutions problems, et cetera?

STEVEN PINKER: The Supreme Court made the right decision. In fact, I signed on to an amicus brief in California when the law was first challenged, because the science that attempts to show that watching violent video games makes kids violent is bad science. Most of it is blank-slate science: they do correlations showing that the kids who like violent entertainment are also kids who commit more violence, and they leap from cause to effect without factoring in the possibility that violent people like violent entertainment.

In terms of cause and effect, there's little, if any, evidence for a causal relationship, aside from irrelevant findings like, if you show kids the Three Stooges, they run around the lab a lot more—that's the "science." And historically, the great age of video game violence, which has been since the 1990s (and it is gruesome stuff) are exactly the decades in which violence in the United States plummeted.

Violent crime in all western countries has declined. There was an opposite trend I haven’t talked about, but you may have noticed in the graphs: when I plotted the rate of violence in European countries from the Middle Ages to the present, it went way down, and then there was a little uptick in the 1960s. It was a little bounce in violence that lasted through the '60s, '70s and '80s then got reversed in the '90s. This decade has brought us back to some of the lowest rates of violence in American history, 4.8 per 100,000 per year. (The lowest was 4.0, in the late '50s.) The new decline took place exactly when video games exploded. And there's a reason for the lack of a causal relationship.

Violent entertainment goes way back, including special effects by Shakespearean actors who would have concealed bladders filled with pig blood, so that when one stabbed the other, there would be a big spurt of gore. People have always liked violent entertainment. The correlation with behavior is poor because of the way human motivation works. When are people violent? It's when they want someone else to come to harm. That accounts for most of the variance in violence. How often you see it done, whether you see it done in your imagination, is separate from how many other people in the world you want dead. And that's why I think that video games are a red herring.

DANIEL KAHNEMAN: Have you commented on what happens on the statistics of soldiers firing their guns?

STEVEN PINKER: Yes. There is a widely spread factoid that most soldiers are inhibited from firing their guns in a battle.

DANIEL KAHNEMAN: There has been training that is very effective so that soldiers currently do fire their guns.

STEVEN PINKER: Yes. And this is sometimes used in the service of the idea that we have innate inhibitions against killing.

There is, I agree, such a feature of human psychology: we don't physically harm another person, particularly an innocent stranger, lightly. The reason that this feature of human psychology is misleading is that it's an inhibition that is not only easy to overcome, but pleasurable to overcome. It's in the same category as an aversion to eating spicy foods or strong cheese or rock climbing. There is an innate tendency to avoid it but there's tremendous pleasure taken in overcoming that avoidance. And of course, the history of hand-to-hand combat going back to Homeric Greece shows that people very easily lose whatever inhibitions they have against causing direct bodily harm.

The second reason that an aversion to hands-on killing is misleading is that most human violence is not mano-a-mano physical conflict, but "cowardly violence." It's pre-dawn raids, it's ambushes, it's drive-by shootings. The inhibition we have works as follows: If you meet an adversary, then since on average he will be as big and strong and mean as you are, you should not give him reason to kill you by attacking him when there’s nothing in it for you (as in a conscript army in battle against a national enemy). But when you can get away with violence without fear of reprisal, inhibitions are gone. In tribal conflict, that's where the big numbers pile up—sneaky ambushes and raids.

One reason I think anthropologists were misled about non-state violence, until they started counting rates of death in primitive warfare, is that they only looked at "pitched battles," where you have the two sides in war paint with spears and drums and they make a lot of noise and then one side backs down. That led to the conclusion that primitive violence is only ritualistic. But the observers didn't count all the times in which one tribe would tiptoe into another village before dawn, then fire arrows through people as they left their huts in the morning to pee, and then annihilate the entire village. That's what gives rise to the high counts.

JOHN TOOBY: As you know, I'm in agreement with almost all of your argument, especially about very long term trends. Very well founded are the events that are aggregated over large populations. But when you start to enter a world with small numbers of nation states, individual events count, individual decision makers count, as you say. And so if you look at World War II, right before World War II, fascism independently took control in Italy and Portugal, Spain, Germany, Hungary, on and on. Add in the Marxian, Soviet celebration of a certain type of war. Then essentially, all of continental Europe except the Netherlands and Switzerland and a few small places went in that direction.

Then, if you look at the outcome of the war, it was a very close thing, that is, for a while it was only Britain against the continent of Europe and it could have very easily gone in the George Orwell direction. …

STEVEN PINKER: In fact it did in half of Europe, the eastern half ...

JOHN TOOBY: Exactly. That's one cautionary element to me. And then I think about what's the likelihood that every conceivable trend would be in the right direction. For example, it's hard to look at what I think of as the writ of the Enlightenment, liberal democracy as spreading inevitably when in fact it was spread by the armies of the English-speaking peoples—imposed by force on Japan and Continental Europe in World War II. And then if you look at other places—you would like to think, and when I was young, I used to think that spontaneously, everybody would vote for democracy if they could. But you look at places like Africa or the Middle East, and they've proven remarkably resistant, and high levels of warfare go on with this resistance.

One also wonders whether the world has now crossed a threshold with, for example, the rise of automatic weapons. Could the U.S. have formed a liberal democracy if everybody had had automatic weapons? Or is it the same kind of thing as the Colonies, even though every teenager in Africa, 13 year olds—not everyone, but large numbers—have automatic weapons. You have this hellish circumstance, and you wonder, would it have been similar here?

I'm also worried that the initial sort of liberal revolution that led to this sort of openness and a cosmopolitan direction also leads culturally to people in these democracies who are now largely unwilling to defend themselves. If you look at Europe, Secretary of Defense Gates said they are unable to sustain a campaign of more than a few weeks outside of Europe.

STEVEN PINKER: Robert Kagan says, "Americans are from Mars, Europeans are from Venus."

JOHN TOOBY: But even in the U.S., blue-staters are European. If you look at who goes into the army, there are all of these myths that it is stupid people or ignorant people or the poor, but it's not. It's middle class, rural people who are slightly better educated than average and who are religious. Those people are getting fewer in the liberal cosmopolitan revolution. Dennis Miller has the line that we have our pet medications Federal Expressed to our front doors, and al-Qaeda looks at that, and thinks, we can take those guys.

STEVEN PINKER: Those are both excellent questions. Okay, the first one. It is certainly true that there can be enormously contingent events where a small number of people can do a lot of damage, and those uncommon but consequential events can blindside you. And that was why, in answer to Ben's question, I cited that as the kind of thing that could go wrong.

But there are two ways of thinking about it. You could say we've been amazingly lucky and it could all blow at any moment. But you could also say that the world just went through an extraordinary run of bad luck. If Hitler had been gassed a little bit more thoroughly in the trenches in World War I, there probably would have been no World War II in Europe, there probably would have been no nuclear arms race, et cetera, et cetera.

So it goes both ways. The question is, how have the odds been shifting? Is the probability of Hitler coming to power in Germany now the same as it was in the '30s? It's not zero. But it's probably less.

A few years ago you could have worried that large parts of the world just couldn't stand the idea of liberal democracy. With the Arab Spring we have to reassess even that. And the Arab spring did not just come out of the blue in the last six months. A Gallup poll of the Islamic world conducted in 2005 had a lot of surprises. There was a large current of liberalism that was seething beneath the surface of the ayatollahs and theocrats on the one side, and the oily kleptocrats on the other side. I wouldn't say a majority—the numbers depend on the country—but support for democracy, freedom of speech, women's rights was found in a substantial proportion of the Islamic world, in some of the countries a majority, which makes the Arab Spring not a total surprise.

Now, I wouldn't go so far as, say, Francis Fukuyama, who suggests that history has a momentum in that direction, that we’re seeing a grand dialectical process culminating in "the end of history." I would localize it to more circumscribed processes like technology, cosmopolitanism, and the spread of ideas. But we can't discount the possibility that liberal democracy ultimately is a pretty attractive vision. And that maybe, like cell phones, when it's available it becomes a gadget that most people find appealing. I wouldn't predict with confidence that that's going to happen, but I wouldn't be surprised if it happened.

Return to Edge Master Class 2011: The Science of Human Nature

|

"We'd certainly be better off if everyone sampled the fabulous Edge symposium, which, like the best in science, is modest and daring all at once." — David Brooks, New York Times column

Future Science, edited by Max Brockman 18 original essays by the brightest young minds in science: Kevin P. Hand - Felix Warneken - William McEwan - Anthony Aguirre -Daniela Kaufer and Darlene Francis - Jon Kleinberg - Coren Apicella - Laurie R. Santos - Jennifer Jacquet - Kirsten Bomblies - Asif A. Ghazanfar - Naomi I. Eisenberger - Joshua Knobe - Fiery Cushman - Liane Young - Daniel Haun - Joan Y. Chiao "A fascinating and very readable summary of the latest thinking on human behaviour." — [More]

"Cool and thought-provoking material. ... so hip." — Washington Post The Best of Edge: The Mind, edited by John Brockman 18 conversations and essays on the brain, memory, personality and happiness: Steven Pinker - George Lakoff - Joseph LeDoux -Geoffrey Miller - Steven Rose - Frank Sulloway - V.S. Ramachandran - Nicholas Humphrey - Philip Zimbardo - Martin Seligman -Stanislas Dehaene - Simon Baron-Cohen - Robert Sapolsky - Alison Gopnik - David Lykken - Jonathan Haidt For the past 15 years, literary-agent-turned-crusader-of-human-progress John Brockman has been a remarkable curator of curiosity, long before either "curator" or "curiosity" was a frivolously tossed around buzzword. His Edge.org has become an epicenter of bleeding-edge insight across science, technology and beyond, hosting conversations with some of our era's greatest thinkers (and, once a year, asking them some big questions). Last month marked the release of The Mind, the first volume in The Best of Edge Series, presenting eighteen provocative, landmark pieces—essays, interviews, transcribed talks—from the Edge archive. The anthology reads like a who's who ... across psychology, evolutionary biology, social science, technology, and more. And, perhaps equally interestingly, the tome—most of the materials in which are available for free online—is an implicit manifesto for the enduring power of books as curatorial capsules of ideas. "(A) treasure chest ... A coffer of cutting-edge contemporary thought, The Mind contains the building blocks of tomorrow's history book—whatever medium they may come in—and invites a provocative peer forward as we gaze back at some of the most defining ideas of our time." — [More] The Best of Edge: Culture, edited by John Brockman

17 conversations and essays on art, society, power and technology: Daniel C. Dennett - Jared Diamond - Denis Dutton - Brian Eno -Stewart Brand - George Dyson - David Gelernter - Karl Sigmund - Jaron Lanier - Nicholas A. Christakis - Douglas Rushkoff - Evgeny Morozov - Clay Shirky - W. Brian Arthur - W. Daniel Hillis - Richard Foreman - Frank Schirrmacher We've already ravished The Mind -- the first in a series of anthologies by Edge.org editor John Brockman, curating 15 years' worth of the most provocative thinking on major facets of science, culture, and intellectual life. On its trails comes Culture: Leading Scientists Explore Societies, Art, Power, and Technology—a treasure chest of insight true to the promise of its title. From the origin and social purpose of art to how technology shapes civilization to the Internet as a force of democracy and despotism, the 17 pieces exude the kind of intellectual inquiry and cultural curiosity that give progress its wings. (A) lavish cerebral feast ... one of this year's most significant time-capsules of contemporary thought." —[More] |