Watching that interrogation of the bankers at the Senate hearings, I had the feeling that this is the way karma works in the universe. Everybody is going to do something not quite right as they act out their destiny mechanically, doing what they unthinkingly believe they have to do. The Wall Street people are going to reflexively overshoot and be too greedy. The Senate people are going to reflexively grandstand and be too uninformed and try to rein them in. There isn't going to be an elegant solution to any of this.

Introduction

By John Brockman

When The Reality Club (the forerunner of Edge) was launched in 1980, one of it's founding members was the late Heinz Pagels, a particle physicist at Rockefeller University and president of The New York Academy of Sciences.

It was around that time that Pagels began to talk about themes that revolved around "the importance of biological organizing principles, the computational view of mathematics and physical processes, the emphasis on parallel networks, the importance of nonlinear dynamics and selective systems, the new understanding of chaos, experimental mathematics, the connectionist's ideas, neural networks, and parallel distributive processing. ..."

He understood that the computer provided "a new window on that view of nature." This led to interesting insights into how the new sciences of complexity would impact global financial markets. He had the intuition that we were on the brink of a new epistemology that would transform the scientific enterprise and the way we think about knowledge.

He understood that the computer provided "a new window on that view of nature." This led to interesting insights into how the new sciences of complexity would impact global financial markets. He had the intuition that we were on the brink of a new epistemology that would transform the scientific enterprise and the way we think about knowledge.

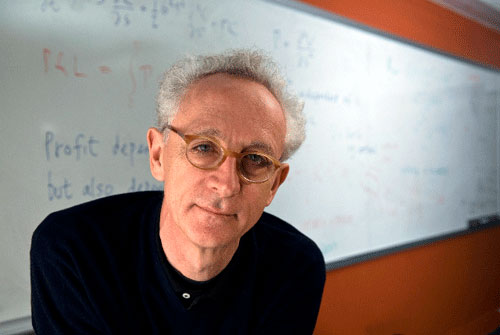

Pagels was having similar conversations at Rockefeller during this period with Emanuel Derman, one of his fellow particle physicists who soon after left academia for a position at Bell Labs, and from there went on to spend 17 years at Goldman Sachs where he became managing director and head of the Quantitative Strategies Group. It was Derman who brought the ideas floating around physics in the 70's and 80's to Wall Street, and in the process came to embody the word "quant."

Writing in the New York Times ("They Tried To Outsmart Wall Street" March 9, 2009) , Denis Overbye observed:

Dr. Derman, who spent 17 years at Goldman Sachs, and became managing director, was a forerunner of the many physicists and other scientists who have flooded Wall Street in recent years, moving from a world in which a discrepancy of a few percentage points in a measurement can mean a Nobel Prize or unending mockery to a world in which a few percent one way can land you in jail and a few percent the other way can win you your own private Caribbean island.

They are known as "quants" because they do quantitative finance. Seduced by a vision of mathematical elegance underlying some of the messiest of human activities, they apply skills they once hoped to use to untangle string theory or the nervous system to making money.

Derman, Overbye noted, "fell in love with a corner of finance that dealt with stock options."

"Options theory is kind of deep in some way. It was very elegant; it had the quality of physics," Derman told him.

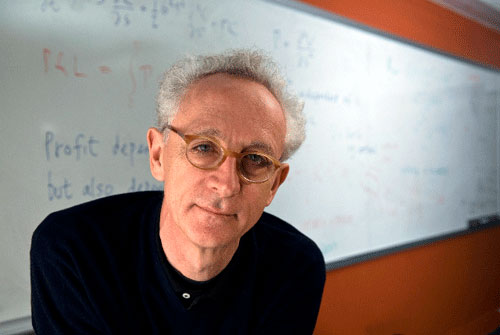

I recently sat down with Derman to ask about his thoughts on the financial crisis, the role played by Goldman and the other big banks, and what new questions we need to ask to get our heads around the big problems which, to some, seem intractable and unsolvable.

Concerning the last point, Pagels was on to something, when, in his 1988 book Dreams of Reason: The Rise of the Sciences of Complexity, he wrote:

Mathematicians and others are endeavoring to apply insights gleaned from the sciences of complexity to the seemingly intractable problem of understanding the world economy. I have a guess, however, that if this problem can be solved (and that is unlikely in the near future), then it will not be possible to use this knowledge to make money on financial markets. One can make money only if there is real risk based on actual uncertainty, and without uncertainty there is no risk.

—JB

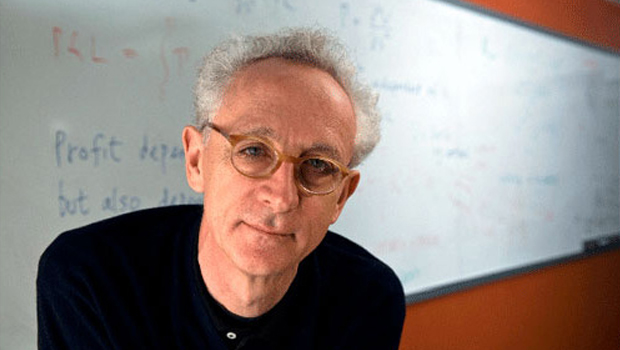

EMANUEL DERMAN, a former managing director and head of the Quantitative Strategies Group at Goldman Sachs & Co, is a professor in Columbia University's Industrial Engineering and Operations Research Department, as well as a partner at Prisma Capital Partners. He is the author of My Life As A Quant.

Emanuel Derman's Edge Bio page