Edge in the News

In 2006, the artist and computer scientist Jaron Lanier published an incisive, groundbreaking and highly controversial essay about “digital Maoism” — about the downside of online collectivism, and the enshrinement by Web 2.0 enthusiasts of the “wisdom of the crowd.” In that manifesto Mr. Lanier argued that design (or ratification) by committee often does not result in the best product, and that the new collectivist ethos — embodied by everything from Wikipedia to“American Idol” to Google searches — diminishes the importance and uniqueness of the individual voice, and that the “hive mind” can easily lead to mob rule.

Jaron Lanier

YOU ARE NOT A GADGET

A Manifesto

By Jaron Lanier

209 pages. Alfred A. Knopf. $24.95.

Related

Bits: Can We Change the Web's Culture of Nastiness?

Excerpt: ‘You Are Not a Gadget’(pdf)

Edge is an organization of deep, visionary thinkers on science and culture. Each year the group poses a question, this year collecting 168 essay responses to the question, "How is the Internet changing the way you think?"

In answer, academics, scientists and philosophers responded with musings on the Internet enabling telecommunication, or functioning as a sort of prosthesis, or robbing us of our old, linear" mode of thinking. ActorAlan Alda described the Web as "speed plus mobs." Responses alternate between the quirky and the profound ("In this future, knowledge will be fully outside the individual, focus will be fully inside, and everybody's selves will truly be spread everywhere.")

Since it takes a while to read the entire collection--and the Atlantic Wire should know, as we tried--here are some of the more piquant answers. Visit the Edge website for the full experience. For a smart, funny answer in video form, see here.

-

We Haven't Changed, declares Harvard physician and sociologist Nicholas Christakis. Our brains "likely evolved ... in response to the demands of social (rather than environmental) complexity," and would likely only continue to evolve as our social framework changes. Our social framework has not changed: from our family units to our military units, he points out, our social structures remain fairly similar to what they were over 1000 years ago. "The Internet itself is not changing the fundamental reality of my thinking any more than it is changing our fundamental proclivity to violence or our innate capacity for love."

- Bordering on Mental Illness Barry C. Smith of the University of London writes of the new importance of "well-packaged information." He says he is personally "exhilarated by the dizzying effort to make connections and integrate information. Learning is faster. Though the tendency to forge connecting themes can feel dangerously close to the search for patterns that overtakes the mentally ill."

Each year, John Brockman of Edge.org asks a question of a number of science, tech, and media personalities, and compiles the answers. This year's question: "How is the internet changing the way you think?" Lots of good, meaty responses that make for great reading, from interesting people whose work ideas have been blogged here on Boing Boing before: Kevin Kelly, Jaron Lanier, Linda Stone, George Dyson, Danny Hillis, Esther Dyson, Tim O'Reilly, Doug Rushkoff, Jesse Dylan, Richard Dawkins, Alan Alda, Brian Eno, and many more.

I'm far out-classed by the aforementioned thinkers. But here's a snip from my more modest contribution, "I DON'T TRUST ALGORITHM LIKE I TRUST INTUITION":

I travel regularly to places with bad connectivity. Small villages, marginalized communities, indigenous land in remote spots around the globe. Even when it costs me dearly, on a spendy satphone or in gold-plated roaming charges, my search-itch, my tweet twitch, my email toggle, those acquired instincts now persist.

The impulse to grab my iPhone or pivot to the laptop, is now automatic when I'm in a corner my own wetware can't get me out of. The instinct to reach online is so familiar now, I can't remember the daily routine of creative churn without it. The constant connectivity I enjoy back home means never reaching a dead end. There are no unknowable answers, no stupid questions. The most intimate or not-quite-formed thought is always seconds away from acknowledgement by the great "out there."

The shared mind that is the Internet is a comfort to me. I feel it most strongly when I'm in those far-away places, tweeting about tortillas or volcanoes or voudun kings, but only because in those places, so little else is familiar. But the comfort of connectivity is an important part of my life when I'm back on more familiar ground, and take it for granted.

"Love Intermedia Kinetic Environments." John Brockman speaking -- partly kidding, but conveying the notion that Intermedia Kinetic Environments are In in the places where the action is -- an Experience, an Event, an Environment, a humming electric world." -- The New York Times

On a Sunday in September 1966, I was sitting on a park bench reading about myself on the front page of the New York Times Arts & Leisure section. I was wondering whether the article would get me fired from my job at the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where I was producing "expanded cinema" and "intermedia" events. I was twenty-five years old.

New and exciting ideas and forms of expression were in the air. They came out of happenings, the dance world, underground movies, avant-garde theater. They came from artists engaged in experiment. Intermedia consisted more often than not of unscripted, sometimes spontaneous theatrical events in which the audience was also a participant. I was lucky enough to have some small part in this upheaval, having been hired a year earlier by the underground filmmaker and critic Jonas Mekas to manage the Filmmakers' Cinémathèque and organize and run the Expanded Cinema Festival.

During that wildly interesting period, many of the leading artists were reading science and bringing scientific ideas to their work. John Cage gave me a copy of Norbert Wiener's Cybernetics; Bob Rauschenberg turned me on to James Jeans' The Mysterious Universe. Claes Oldenburg suggested I read George Gamow's 1,2,3...Infinity. USCO, a group of artists, engineers, and poets who created intermedia environments; La Monte Young's Theatre of Eternal Music; Andy Warhol's Factory; Nam June Paik's video performances; Terry Riley's minimalist music -- these were master classes in the radical epistemology of a set of ideas involving feedback and information.

Another stroke of good luck was my inclusion in a small group of young artists invited by Fluxus artist Dick Higgins to attend a series of dinners with John Cage -- an ongoing seminar about media, communications, art, music, and philosophy that focused on the ideas of Norbert Wiener, Claude Shannon, and Marshall McLuhan. Cage was aware of research conducted in the late 1930s and 1940s by Wiener, Shannon, Vannevar Bush, Warren McCulloch, and John von Neumann, who were all present at the creation of cybernetic theory. And he had picked up on McLuhan's idea that by inventing electric technology we had externalized our central nervous systems -- that is, our minds -- and that we now had to presume that "There's only one mind, the one we all share." We had to go beyond personal mind-sets: "Mind" had become socialized. "We can't change our minds without changing the world," Cage said. Mind as a man-made extension had become our environment, which he characterized as a "collective consciousness" that we could tap into by creating "a global utilities network."

Back then, of course, the Internet didn't exist, but the idea was alive. In 1962, J.C.R Licklider, who had published "Man-Computer Symbiosis" in 1960 and described the idea of an "Intergalactic Computer Network" in 1961, was hired as the first director of the new Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO) at the Pentagon's Advanced Research Projects Agency, an agency created as a response to Sputnik. Licklider designed the foundation for a global computer network. He and his successors at IPTO, including Robert Taylor and Larry Roberts, provided the ideas that led to the development of the ARPAnet, the forerunner of the Internet, which itself emerged as an ARPA-funded research project in the mid-1980s.

Inspired also by architect-designer Buckminster Fuller, futurist John McHale, and cultural anthropologists Edward T. ("Ned") Hall and Edmund Carpenter, I began to read avidly in the field of information theory, cybernetics, and systems theory. McLuhan himself introduced me to The Mathematical Theory of Communication by Shannon and Weaver, which began: "The wordcommunication will be used here in a very broad sense to include all of the procedures by which one mind may affect another. This, of course, involves not only written and oral speech, but also music, the pictorial arts, the theater, the ballet, and in fact all human behavior."

Inherent in these ideas is a radical new epistemology. It tears apart the fabric of our habitual thinking. Subject and object fuse. The individual self decreates. I wrote a synthesis of these ideas in my first book, By the Late John Brockman (1969), taking information theory -- the mathematical theory of communications -- as a model for regarding all human experience. I began to develop a theme that has informed my endeavors ever since: New technologies beget new perceptions. Reality is a man-made process. Our images of our world and of ourselves are, in part, models resulting from our perceptions of the technologies we generate.

We create tools and then we mold ourselves in their image. Seventeenth-century clockworks inspired mechanistic metaphors ("The heart is a pump"), just as the self-regulating engineering devices of the mid-twentieth century inspired the cybernetic image ("The brain is a computer"). The anthropologist Gregory Bateson has characterized the post-Newtonian worldview as one of pattern, of order, of resonances in which the individual mind is a subsystem of a larger order. Mind is intrinsic to the messages carried by the pathways within the larger system and intrinsic also in the pathways themselves.

Ned Hall once pointed out to me that the most critical inventions are not those that resemble inventions but those that appear innate and natural. Once you become aware of this kind of invention, it is as though you had always known about it. ("The medium is the message." Of course, I always knew that).

Hall's candidate for the most important invention was not the capture of fire, the printing press, the discovery of electricity, or the discovery of the structure of DNA. The most important invention was ... talking. To illustrate the point, he told a story about a group of prehistoric cavemen having a conversation.

"Guess what?" the first man said. "We're talking." Silence. The others looked at him with suspicion.

"What's 'talking'?" a second man asked.

"It's what we're all doing, right now. We're talking!"

"You're crazy," the third man said. "I never heard of such a thing!"

"I'm not crazy," the first man said. "You're crazy. We're talking."

Talking, undoubtedly, was considered innate and natural until the first man rendered it visible by exclaiming, "We're talking."

* * *

A new invention has emerged, a code for the collective conscious, which requires a new way of thinking. The collective externalized mind is the mind we all share. The Internet is the infinite oscillation of our collective conscious interacting with itself. It's not about computers. It's not about what it means to be human -- in fact it challenges, renders trite, our cherished assumptions on that score. It's about thinking. "We're talking."

This year's Question is "How is the Internet changing the way YOU think?" Not "How is the Internet changing the way WE think?" We spent a lot of time going back on forth on "YOU" vs. "WE" and came to the conclusion to go with "YOU", the reason being that Edge is a conversation. "WE" responses tend to come across like expert papers, public pronouncements, or talks delivered from stage.

We wanted people to think about the "Internet", which includes, but is a much bigger subject than the Web, an application on the Internet, or search, browsing, etc., which are apps on the Web. Back in 1996, computer scientist and visionary Danny Hillis pointed out that when it comes to the Internet, "Many people sense this, but don't want to think about it because the change is too profound. Today, on the Internet the main event is the Web. A lot of people think that the Web is the Internet, and they're missing something. The Internet is a brand-new fertile ground where things can grow, and the Web is the first thing that grew there. But the stuff growing there is in a very primitive form. The Web is the old media incorporated into the new medium. It both adds something to the Internet and takes something away."

This year, I enlisted the aid of Hans Ulrich Obrist, Curator of the Serpentine Gallery in London, as well as the artist April Gornik, one of the early members of "The Reality Club" (the precursor to the online Edge) to help broaden the Edge conversation -- or rather to bring it back to where it was in the late 80s/early 90s, when April gave a talk at a "Reality Club" meeting, and discussed the influence of chaos theory on her work, and when Benoit Mandelbrot showed up to discuss fractal theory and every artist in NYC wanted to be there. What then happened was very interesting. The Reality Club went online as Edge in 1996 and the scientists were all on email, the artists not. Thus, did Edge surprisingly become a science site when my own background (beginning in 1965 whenJonas Mekas hired me to manage the Film-Makers' Cinematheque) was in the visual and performance arts.

We asked the Edgies to go deeper than the news, the "he said, she said", the tired discussion about the future of media, etc. The editorial marching orders were: "Tell me something I don't know. Explore new ideas about how human beings communicate with each other. As communications is the basis of civilization, this Edge Question is not about computers, not about technology, not about things digital: this is question about our culture and ourselves. The ideas we present here can offer a new set of metaphors to describe ourselves, our minds, the way we think, the world, and all of the things we know in it. ... Be imaginative, exciting, compelling, inspiring. Tell a great story. Make an argument that makes a difference. Amaze and delight. Surprise us!"

To date, 168 essayists (an array of world-class scientists, artists, and creative thinkers) have created a 130,000 document.

I know that the New Year has officially arrived when John Brockman publishes the responses to his Annual Question over at the Edge website.

I know that the New Year has officially arrived when John Brockman publishes the responses to his Annual Question over at the Edge website.

This year, Brockman asked his crew of intellectual heavy-hitters, "How is the internet changing the way you think?"

The answers range from "It's not" to "Everything's going to hell" to "The internet is making us smarter, more social and more evolved" to "Who the hell knows?", with a dose of everything in between.

As I read through the responses, I found myself convinced more than once by conflicting arguments--a classic internet experience, I think. And despite the loudly bemoaned internet-induced ADD epidemic, one can easily spend hours reading through these intriguing responses.

Brockman himself sets the tone with the idea that the internet has formed a sort of collective consciousness and with the conviction that "new technologies beget new perceptions. Reality is a man-made process. Our images of our world and ourselves are, in part, models resulting form our perceptions of the technologies we generate."

Is the internet a cognitive prosthesis, or merely a mirror of old-fashioned human nature? Have we outsourced our memories and faculties of judgment to the virtual universe and the hive mind? What have we sacrificed? What have we gained?

For computer scientist Daniel Hillis, the internet has changed the way we make decisions, as we farm individual choices out to the collective web. "If the theme of the Enlightenment was independence," he writes, "our own theme is interdependence. We are now all connected, humans and machines. Welcome to the Entanglement."

But for those who are overly concerned that such entanglement has usurped individual thought, Larry Sanger, co-founder of Wikipedia, has some advice: "If you feel yourself growing ovine, bleat for yourself."

Nassim Taleb, who has placed himself on a strict internet diet, is worried that "more information causes more confidence and illusions of knowledge while degrading predictability."

For royal astronomer Martin Rees, "the internet enables far wider participation in front-line science", though Philip Campbell, editor-in-chief of Nature, believes this might have happened more readily had Congress not rejected funding for a digitized indexing search infrastructure called PubSCIENCE.

Writer Howard Rheingold reminds us that "attention is the fundamental literacy", advocatingmindfulness of how our attention wanders about the internet as we surf. It makes you wonder whether kids growing up in the internet age ought to be taught in school, as a matter of standard practice, Rheingold's basic elements of internet literacy: attention mindfulness, crap detection, participation, collaboration and network awareness.

I think Paul Saffo, a technology forecaster at Stanford University, might agree. Saffo paraphrases Samuel Johnson, who said that there are two kinds of knowledge: that which you know and that which you know where to get. Now, Saffo says, we don't have to know where to get information--the internet does that for us. But perhaps there is now a third kind of knowledge: the knowledge of what matters.

I was intrigued by the comparisons between the internet and multicellularity in biological organisms discussed by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins and cognitive biologist W. Tecumseh Fitch.

But my favorite responses were geneticist George Church's cleverly hyperlinked piece, "Sorry, John, no time to think about the Edge question", architect Neri Oxman's comparisons to Borges and her suggestion that in the light of the internet "models become the very reality that we are asked to model", and David Eagleman's "Six ways the internet may save civilization".

Another favorite of mine was the piece by neuro-philosopher Thomas Metzinger, who serves upthis fascinating food for thought:

Here is something we are just beginning to understand -- that the Internet affects our sense of selfhood, and on a deep functional level.

Consciousness is the space of attentional agency: Conscious information is exactly that information in your brain to which you can deliberately direct your attention. As an attentional agent, you can initiate a shift in attention and, as it were, direct your inner flashlight at certain targets: a perceptual object, say, or a specific feeling. In many situations, people lose the property of attentional agency, and consequently their sense of self is weakened. Infants cannot control their visual attention; their gaze seems to wander aimlessly from one object to another, because this part of their Ego is not yet consolidated. Another example of consciousness without attentional control is the non-lucid dream state. In other cases, too, such as severe drunkenness or senile dementia, you may lose the ability to direct your attention -- and, correspondingly, feel that your "self" is falling apart.

If it is true that the experience of controlling and sustaining your focus of attention is one of the deeper layers of phenomenal selfhood, then what we are currently witnessing is not only an organized attack on the space of consciousness per se but a mild form of depersonalization. New medial environments may therefore create a new form of waking consciousness that resembles weakly subjective states -- a mixture of dreaming, dementia, intoxication, and infantilization. Now we all do this together, every day. I call it Public Dreaming.

So go celebrate the New Year with the brains at the Edge and remember, without the internet, you wouldn't have this awesome concentration of intellectual power. Then again, as software pioneer Kai Krause points out, these answers will soon end up in the form of a good old-fashioned book.

Das Onlinemagazin Edge hat Wissenschaftler, Autoren und Künstler gefragt, wie das Internet ihr Denken verändert hat. Die Antworten sind bemerkenswert.

Zwei Milliarden Menschen nutzen weltweit das Internet. Die Debatten um die neue Technologie verlaufen allerdings nicht überall gleich. In Deutschland beispielsweise beschränken sich die Diskurse um das Netz vor allem auf Medien- und Urheberrechtsdebatten.

Die Veröffentlichung von "Payback", dem Buch des FAZ-Mitherausgebers Frank Schirrmacher hat der deutschen Debatte zwar die Tiefe gegeben, die das Thema verdient.

Im Vorfeld der Veröffentlichung gab Frank Schirrmacher dem amerikanischen Literaturagent John Brockman ein Interview für dessen Onlinemagazin für Wissenschaftskultur Edge.org.

Da ging es auch um die Frage, die Schirrmacher in seinem Buch behandelt - wie verändert dasInternet das Denken? Brockman hat diese Frage nun aufgegriffen, und sie als seine Grundsatzfrage formuliert, die er am Ende jedes Jahres den Wissenschaftlern und Autoren stellt, die auf Edge debattieren und veröffentlichen.

Die Antworten wurden jetzt auf Edge.org veröffentlicht. Die Autoren sind 131 einflussreiche Wissenschaftler, Autoren und Künstler.

Mehr zerstreut als unterstützt

Die Antworten fielen sehr unterschiedlich aus. Und doch ist die Sammlung kurzer Essays ein gutes Beispiel dafür, auf welchem Niveau in den USA über das Internet debattiert wird. Wobei sich die Debatte keineswegs auf die zwei Lage der Zukunftseuphoriker und Kulturpessimisten beschränkt.

Und selbst wenn man selbst die Dinge anders sieht, fordern auch die kulturpessimistische Ansätze wie zum Beispiel die Aufsätze des Schriftstellers Nicholas Carr, des Medientheoretikers Douglas Rushkoff und des Mathematikers Nassim Taleb zum Nachdenken auf, anstatt zu Widerspruch zu reizen.

Taleb wird übrigens von der Veröffentlichung seines Textes nicht viel mitbekommen haben. Taleb ist bis zum Sommer 2010 bewusst offline. Und siehe da: "Ich fühle, wie ich wieder wachse", schreibt er. Wo die Online-Abstinenz zur Heilung wird, erscheint das Internet als Krankheit.

Dabei gesteht Taleb ein, dass "Technologien das Beste auf der Welt sind." Aber vom Internet fühlt er sich doch mehr zerstreut als unterstützt, der Wissenszuwachs im und durch das Netz erscheint dem Mathematiker als Illusion: "Wir denken wir wissen mehr als wir wirklich wissen", die Welt sei einer intellektuellen Hybris verfallen.

Bestes Beispiel dafür ist für ihn, dass auch das schier endlose Wissen des Netzes die Finanzkrise niemanden erahnen ließ. Taleb hingegen hatte im Jahr 2007 detailliert vor einem Zusammenbruch der Banken gewarnt.

I know that the New Year has officially arrived when John Brockman publishes the responses to his Annual Question over at the Edge website.

This year, Brockman asked his crew of intellectual heavy-hitters, "How is the internet changing the way you think?"

The answers range from "It's not" to "Everything's going to hell" to "The internet is making us smarter, more social and more evolved" to "Who the hell knows?", with a dose of everything in between.

As I read through the responses, I found myself convinced more than once by conflicting arguments--a classic internet experience, I think. And despite the loudly bemoaned internet-induced ADD epidemic, one can easily spend hours reading through these intriguing responses. Brockman himself sets the tone with the idea that the internet has formed a sort of collective consciousness and with the conviction that "new technologies beget new perceptions. Reality is a man-made process. Our images of our world and ourselves are, in part, models resulting form our perceptions of the technologies we generate."

Is the internet a cognitive prosthesis, or merely a mirror of old-fashioned human nature? Have we outsourced our memories and faculties of judgment to the virtual universe and the hive mind? What have we sacrificed? What have we gained?

For computer scientist Daniel Hillis, the internet has changed the way we make decisions, as we farm individual choices out to the collective web. "If the theme of the Enlightenment was independence," he writes, "our own theme is interdependence. We are now all connected, humans and machines. Welcome to the Entanglement."

But for those who are overly concerned that such entanglement has usurped individual thought, Larry Sanger, co-founder of Wikipedia, has some advice: "If you feel yourself growing ovine, bleat for yourself." Nassim Taleb, who has placed himself on a strict internet diet, is worried that "more information causes more confidence and illusions of knowledge while degrading predictability." For royal astronomer Martin Rees, "the internet enables far wider participation in front-line science", though Philip Campbell, editor-in-chief of Nature, believes this might have happened more readily had Congress not rejected funding for a digitized indexing search infrastructure called PubSCIENCE.

Writer Howard Rheingold reminds us that "attention is the fundamental literacy", advocatingmindfulness of how our attention wanders about the internet as we surf. It makes you wonder whether kids growing up in the internet age ought to be taught in school, as a matter of standard practice, Rheingold's basic elements of internet literacy: attention mindfulness, crap detection, participation, collaboration and network awareness.

I think Paul Saffo, a technology forecaster at Stanford University, might agree. Saffo paraphrases Samuel Johnson, who said that there are two kinds of knowledge: that which you know and that which you know where to get. Now, Saffo says, we don't have to know where to get information--the internet does that for us. But perhaps there is now a third kind of knowledge: the knowledge of what matters.

I was intrigued by the comparisons between the internet and multicellularity in biological organisms discussed by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins and cognitive biologist W. Tecumseh Fitch. But my favorite responses were geneticist George Church's cleverly hyperlinked piece, "Sorry, John, no time to think about the Edge question", architect Neri Oxman's comparisons to Borges and her suggestion that in the light of the internet "models become the very reality that we are asked to model", and David Eagleman's "Six ways the internet may save civilization".

Another favorite of mine was the piece by neuro-philosopher Thomas Metzinger, who serves upthis fascinating food for thought:

Here is something we are just beginning to understand -- that the Internet affects our sense of selfhood, and on a deep functional level.

Consciousness is the space of attentional agency: Conscious information is exactly that information in your brain to which you can deliberately direct your attention. As an attentional agent, you can initiate a shift in attention and, as it were, direct your inner flashlight at certain targets: a perceptual object, say, or a specific feeling. In many situations, people lose the property of attentional agency, and consequently their sense of self is weakened. Infants cannot control their visual attention; their gaze seems to wander aimlessly from one object to another, because this part of their Ego is not yet consolidated. Another example of consciousness without attentional control is the non-lucid dream state. In other cases, too, such as severe drunkenness or senile dementia, you may lose the ability to direct your attention -- and, correspondingly, feel that your "self" is falling apart.

If it is true that the experience of controlling and sustaining your focus of attention is one of the deeper layers of phenomenal selfhood, then what we are currently witnessing is not only an organized attack on the space of consciousness per se but a mild form of depersonalization. New medial environments may therefore create a new form of waking consciousness that resembles weakly subjective states -- a mixture of dreaming, dementia, intoxication, and infantilization. Now we all do this together, every day. I call it Public Dreaming.

So go celebrate the New Year with the brains at the Edge and remember, without the internet, you wouldn't have this awesome concentration of intellectual power. Then again, as software pioneer Kai Krause points out, these answers will soon end up in the form of a good old-fashioned book.

The online magazine Edge asked scientists, writers and artists, such as the Internet has changed their thinking. The answers are remarkable. ...

Two billion people worldwide use the Internet. The debates about the new technology, however, are not the same everywhere. In Germany, for example, the discourse is limited on the subject of the net, as it is especially focused on media and copyright debates.

The publication of the book "Payback", co-editor Frank Schirrmacher, co-editor of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung presents the German debate, giving the topic the the depth it deserves.

Prior to the publication Schirrmacher 's book, the American literary agent John Brockman, interviewed him for Edge.org, the online science and culture magazine.

Schirrmacher, in his book, also asked the question — Has the Internet changed thinking? Brockman has now taken up this issue, and formulated it as his fundamental question, which he asks at the end of each year of the scientists and authors who discuss and publish on Edge.

The answers have now been published on Edge.org. The authors are 131 influential scientists, authors and artists.

Does the Web change how we think?

Shortened attention span. Less interest in reflection and introspection. Inability to engage in in-depth thought. Fragmented, distracted thinking.

The ways the Internet supposedly affects thought are as apocalyptic as they are speculative, since all the above are supported by anecdote, not empirical data. So it is refreshing to hear how 109 philosophers, neurobiologists, and other scholars answered, "How is the Internet changing the way you think?" That is the "annual question" at the online salon edge.org, where every year science impresario, author, and literary agent John Brockman poses a puzzler for his flock of scientists and other thinkers.

Although a number of contributors drivel on about, say, how much time they waste on e-mail, the most striking thing about the 50-plus answers is that scholars who study the mind and the brain, and who therefore seem best equipped to figure out how the Internet alters thought, shoot down the very idea. "The Internet hasn't changed the way we think," argues neuroscientist Joshua Greene of Harvard. It "has provided us with unprecedented access to information, but it hasn't changed what [our brains] do with it." Cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker of Harvard is also skeptical. "Electronic media aren't going to revamp the brain's mechanisms of information processing," he writes. "Texters, surfers, and twitterers" have not trained their brains "to process multiple streams of novel information in parallel," as is commonly asserted but refuted by research, and claims to the contrary "are propelled by ... the pressure on pundits to announce that this or that 'changes everything.' "

And yet. Many scholars do believe the Internet alters thinking, and offer provocative examples of how—many of them surprisingly dystopian. Communications scholar Howard Rheingold believes the Internet fosters "shallowness, credulity, distraction," with the result that our minds struggle "to discipline and deploy attention in an always-on milieu." (Though having to make a decision every time a link appears—to click or not to click?—may train the mind's decision-making networks.) The Internet is also causing the "disappearance of retrospection and reminiscence," argues Evgeny Morozov, an expert on the Internet and politics. "Our lives are increasingly lived in the present, completely detached even from the most recent of the pasts ... Our ability to look back and engage with the past is one unfortunate victim." Cue the Santayana quote.

These changes in what people think are accompanied by true changes in the process of thinking—little of it beneficial. The ubiquity of information makes us "less likely to pursue new lines of thought before turning to the Internet," writes psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi of Claremont Graduate University. "Result: less sustained thought?" And since online information "is often decontextualized," he adds, it "satisfies immediate needs at the expense of deeper understanding (result: more superficial thought?)." Because facts are a click away, writes physicist Haim Harari, "the Internet allows us to know fewer facts ... reducing their importance as a component" of thought. That increases the importance of other components, he says, such as correlating facts, "distinguishing between important and secondary matters, knowing when to prefer pure logic and when to let common sense dominate." By flooding us with information, the Internet also "causes more confidence and illusions of knowledge" (Nassim Taleb of MIT, author of The Black Swan), but makes our knowledge seem "more fragile," since "for every accepted piece of knowledge I find, there is within easy reach someone who challenges the fact" (Kevin Kelly, cofounder of Wired).

Even more intriguing are the (few) positive changes in thinking the Internet has caused. The hyperlinked Web helps us establish "connections between ideas, facts, etc.," suggests Csikszentmihalyi. "Result: more integrated thought?" For Kelly, the uncertainty resulting from the ubiquity of facts and "antifacts" fosters "a kind of liquidity" in thinking, making it "more active, less contemplative." Science historian George Dyson believes the Internet's flood of information has altered the process of creativity: what once required "collecting all available fragments of information to assemble a framework of knowledge" now requires "removing or ignoring unnecessary information to reveal the shape of knowledge hidden within." Creativity by destruction rather than assembly.

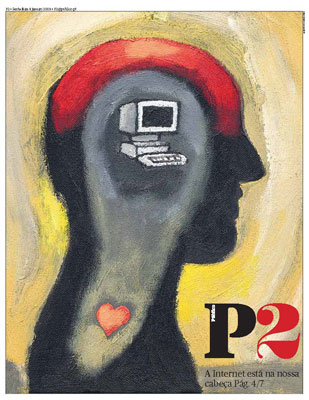

Do you think the Internet has altered you mind at the neuronal, cognitive, processing, emotional levels? Yes, no, maybe, reply philosophers, scientists, writers, journalists to the Edge annual question 2010, in dozens of texts that are published online today

Ana Gerschenfeld

Click here for PDF of Portuguese Original

In the summer of 2008, American writer Nicholas Carr published in the Atlantic Monthly an article under the titleIs Google making us stupid?: What the Internet is doing to our brains, in which highly criticized the Internet’s effects on our intellectual capabilities. The article had a high impact, both in the media and the blogosphere.

Edge.org – the intellectual online salon – has now expanded and deepened the debate through its traditional annual challenge to dozens of the world’s leading thinkers of science, technology, thought, arts, journalism. The 2010 question is: “How is the Internet changing the way you think?"

They reply that the Internet has made them (us) smarter, shallower, faster, less attentive, more accelerated, less creative, more tactile, less visual, more altruistic, less arrogant. That it has dramatically expanded our memory but at the same time made us the hostages of the present tense. The global web is compared to an ecosystem, a collective brain, a universal memory, a global conscience, a total map of geography and history.

One thing is certain: be they fans or critics, they all use it and they all admit that the Internet leaves no one untouched. No one can remain impervious to things such a Wikipedia or Google, no one can resist the attraction of instant, global, communication and knowledge.

More than 120 scientists, physicians, engineers, authors, artists, journalists met the challenge. Here, we present the gist some of their answers, including Nicholas Carr’s, who is also part of this online think tank founded by New-York literary agent John Brockman. If you have more time and think your attention span is up to it, we recommend you enjoy the whole scope of their length and diversity by visiting edge.org

Who decides?

Daniel Hillis

Physicist, Computer Scientist

The real impact of the Internet is that it has changed the way we make decisions. More and more, it is not individual humans who decide, but an entangled, adaptive network of humans and machines. Although we created it, we did not exactly design it. It evolved. Our relationship to it is similar to our relationship to our biological ecosystem. We are co-dependent, and not entirely in control.

Speed of thinking

Andrian Kreye

Editor, Sueddeutsche Zeitung

If speeding up thinking continually constitutes changing the way I think, the Internet has done a marvelous job. All this might not constitute a change in thinking though. I haven't changed my mind or my convictions because of the Internet. I haven't had any epiphanies while sitting in front of a screen. The Internet so far has not given me no memorable experiences, although it might have helped to usher some along. It has always been people, places and experiences that have changed the way I think.

Facsimile of experience

Eric Fischl and April Gornik

Visual Artists

For the visual artist, seeing is essential to thought. So how has the Internet changed us visually? The changes are subtle yet profound. One loss is a sense of scale. Another is a loss of differentiation between materials. Visual information becomes based on image alone. Experience is replaced with facsimile.

Work and play

Kevin Kelly

Editor-At-Large, Wired

I am "smarter" in factuality, but my knowledge is now more fragile. Anything I learn is subject to erosion. My certainty about anything has decreased. That means that in general I assume more and more that what I know is wrong. The Internet also blurs the difference between my serious thoughts and my playful thoughts. I believe the conflation of play and work, of thinking hard and thinking playfully, is one the greatest things the Internet has done.

Digital sugar

Esther Dyson

Former Chairman, Electronic Frontier Foundation

I love the Internet. But sometimes I think much of what we get on the Internet is empty calories. It's sugar – short videos, pokes from friends, blog posts, Twitter posts, pop-ups and visualizations… Over a long period, many of us are genetically disposed to lose our capability to digest sugar if we consume too much of it. Could that be true of information sugar as well? Will we become allergic to it even as we crave it? And what will serve as information insulin?

Mind control

Larry Sanger

Co-founder of Wikipedia

Some observers speak of how our minds are being changed by information overload, apparently despite ourselves. Former free agents are mere subjects of powerful new forces. I don't share the assumption. Do we have any choice about ceding control of the self to an increasingly compelling "Hive Mind"? Yes. And should we cede such control, or instead strive, temperately, to develop our own minds very well and direct our own attention carefully? The answer, I think, is obvious.

Outsourcing the mind

Gerd Gigerenzer

Psychologist, Max Planck Institute

We are in the process of outsourcing information storage and retrieval from mind to computer, just as many of us have already outsourced the ability of doing mental arithmetic to the pocket calculator. We may loose some skills in this process, but the Internet is also teaching us new skills for accessing information. The Internet is a kind of collective memory, to which our minds will adapt until a new technology eventually replaces it. Then we will begin outsourcing other cognitive abilities, and hopefully, learn new ones.

Thinking better

Stephen Kosslyn

Psychologist, Harvard University

The Internet has extended my memory, perception, and judgment. These effects have become even more striking since I've used a smart phone. I now regularly pull out my phone to check a fact, to watch a video, and to read blogs. The downside is that when I used to have dead periods, I often would let my thoughts drift, and sometimes would have an unexpected insight or idea. Those opportunities are now fewer and farther between. But I think it's a small price to pay. I am a better thinker now than I was before I integrated the Internet into my mental and emotional processing.

Dramatic changes

Kai Kraus

Software Pioneer|

The Internet dramatically changed my own thinking. Not at the neuron level, but more abstractly: it completely redefined how we perceive the world and ourselves in it. But it is a double-edged sword, a yin-yang yoyo of the good, the bad and the ugly. The Net will not reach its true potential in my little lifetime. But it surely has influenced the thinking in my lifetime like nothing else ever has.

Tactile cyberworld

James O'Donnell

Classicist, Georgetown University

My fingers have become part of my brain. Just for myself, just for now, it's my fingers I notice. Ask me a good question today, and if I am away from my desk, I pull out my Blackberry – it's a physical reaction, a gut feeling that I need to start manipulating the information at my fingertips. At my desktop, it's the same pattern: the sign of thinking is that I reach for the mouse and start "shaking it loose". My eyes and hands have already learned to work together in new ways with my brain in a process that really is a new way of thinking for me. The information world is more tactile than ever before.

Promiscuity

Seth Lloyd

Quantum Mechanical Engineer, MIT

I think less. When I do think, I am lazier. For hundreds of millions of years, sex was the most efficient method for propagating information of dubious provenance: the origins of all those snippets of junk DNA are lost in the sands of reproductive history. The world-wide Web has usurped that role. A single illegal download can propagate more parasitic bits of information than a host of mating Tse Tse flies. For the moment, however, the ability of the Internet to propagate information promiscuously is largely a blessing. What will happen later? Don't ask me. By then, I hope not to be thinking at all.

Same old brain

Nicholas Christakis

Physician and Social Scientist, Harvard University

The Internet is no different than previous (equally monumental) brain-enhancing technologies such as books or telephony, and I doubt whether books and telephony have changed the way I think, in the sense of actually changing the way my brain works. In fact, I would say that it is much more correct to say that our thinking gave rise to the Internet than that the Internet gave rise to our thinking. There is no new self. There are no new others. And so there is no new brain, and no new way of thinking. We are the same species after the Internet as before.

The map

Neri Oxman

Architect, Researcher, MIT

The Internet has become a map of the world, both literally and symbolically, as it traces in an almost 1:1 ratio every event that has ever taken place. As we are fed with information, thus withers the very power of perception, and the ability to engage in abstract and critical thought atrophies. Where are we heading in the age of the Internet? Are we being victimized by our own inventions?

Hunter-gatherers

Lee Smolin

Physicist, Perimeter Institute

The Internet hasn't, so far, changed how we think. But it has radically altered the contexts in which we think and work. We used to cultivate thought, now we have become hunter-gatherers of images and information. Perhaps when the Internet has been soldered into our glasses or teeth, with the screen replaced by a laser making images directly on our retinas, there will be deeper changes.

The Matrix

John Markoff

Journalist, The New York Times

Not only have I been transformed into an Internet pessimist, but recently the Net has begun to feel downright spooky. Doesn't the Net seem to have a mind of its own? Will we all be assimilated, or have we been already? Wait! Stop me! That was The Matrix wasn't it?

The upload has begun

Sam Harris

Neuroscientist, The Reason Project

It is now a staple of scientific fantasy, or nightmare, to envision that human minds will one day be uploaded onto a vast computer network like the Internet. I notice that the prophesied upload is slowly occurring in my own case. This migration to the Internet now includes my emotional life. Increasingly, I develop relationships with other scientists and writers that exist entirely online. Almost every sentence we have ever exchanged exists in my Sent Folder. Our entire relationship is, therefore, searchable. I have many other friends and mentors who exist for me in this way, primarily as email correspondents.

Parallel Lives

Linda Stone

Former Executive at Apple and Microsoft

Before the Internet, I made more trips to the library and more phone calls. I read more books and my point of view was narrower and less informed. I walked more, biked more, hiked more, and played more. I made love more often. The more I've loved and known it, the clearer the contrast, the more intense the tension between a physical life and a virtual life. The sense of contrast between my online and offline lives has turned me back toward prizing the pleasures of the physical world. I now move with more resolve between each of these worlds, choosing one, then the other – surrendering neither.

The Dumb Butler

Joshua Greene

Cognitive Neuroscientist and Philosopher, Harvard University

The Internet hasn't changed the way we think anymore than the microwave oven has changed the way we digest food. The Internet has provided us with unprecedented access to information, but it hasn't changed what we do with it once it's made it into our heads. This is because the Internet doesn't (yet) know how to think. We still have to do it for ourselves, and we do it the old-fashioned way. Until then, the Internet will continue to be nothing more, and nothing less, than a very useful, and very dumb, butler.

The end of experience

Scott Sampson

Dinosaur paleontologist

What I want to know how the Internet changes the way the children of the Internet age think. It seems likely that a lifetime of daily conditioning dictated by the rapid flow of information across glowing screens will generate substantial changes in brains, and thus thinking. But I have a larger fear, one rarely mentioned – the extinction of experience, the loss of intimate experience with the natural world. Any positive outcome will involve us turning off the screens and spending significant time outside interacting with the real world, in particular the nonhuman world.

Rewired

Haim Harari

Physicist, former President, Weizmann Institute of Science

There are three clear changes that are palpable. The first is the increasing brevity of messages. The second is the diminishing role of factual knowledge, in the thinking process. The third is in the entire process of teaching and learning: it may take another decade or two, but education will never be the same. An interesting follow-up issue, to this last comment, is the question whether the minds and brains of children will be physically "wired" differently than those of earlier generations. I tend to speculate in the affirmative.

The Price of omniscience

Terrence Sejnowski

Computational Neuroscientist, Salk Institute

Experiences have long-term effects on the brain's structure and function. Are the changes occurring in your brain as you interact with the Internet good or bad for you? Gaining knowledge and skills should benefit survival, but not if you spend all of your time immersed in the Internet. The intermittent rewards can become addictive. The Internet, however, has not been around long enough, and is changing too rapidly, to know what the long-term effects will be on brain function. What is the ultimate price for omniscience?

Thinking like the Internet

Nigel Goldenfeld

Physics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

I don't believe my way of thinking was changed by the Internet until around 2000. Why not? The answer, I suspect, is the fantastic benefit that comes from massive connectivity and the resulting emergent phenomena. Back in those days, the Internet was linear, predictable, and boring. It never talked back. But I'm starting to think like the Internet. My thinking is better, faster, cheaper and more evolvable because of the Internet. And so is yours. You just don't know it yet.

Greatest Detractor

Leo Chalupa

Neurobiologist, University of California, Davis

The Internet is the greatest detractor to serious thinking since the invention of television. Moreover, while the Internet provides a means for rapidly communicating with colleagues globally, the sophisticated user will rarely reveal true thoughts and feelings in such messages. Serious thinking requires honest and open communication and that is simply untenable on the Internet by those that value their professional reputation.

The Collective Brain

Matt Ridley

Science Writer

Cultural and intellectual evolution depends on sex just as much as biological evolution does. Sex allows creatures to draw upon mutations that happen anywhere in their species. The Internet allows people to draw upon ideas that occur to anybody in the world. This has changed the way I think about human intelligence. The Internet is the latest and best expression of the collective nature of human intelligence.

Memory sharpener

Tom Standage

Editor, The Economist

The Internet has not changed the way I think. What the Internet has done, however, is sharpen my memory. A quick search with a few well chosen keywords is usually enough to turn a decaying memory of a half-forgotten item into perfect recall of the information in question. This is useful now, but I expect it to become much more useful as I get older and my memory starts to become less reliable. Perhaps the same will be true of the way the Internet enhances our mental faculties in the years to come.

People in my head

Eva Wisten

Journalist, SEED Media Group

The Internet might not be changing how I think, but it does some of my thinking for me. And above all, the Internet is changing how I see myself. As real world activity and connections continue to be what matters most to me, the Internet, with its ability to record my behavior, is making it clearer that I am, in thought and in action, the sum of the thoughts and actions of other people to a greater extent than I have realized.

Internet natives

Alison Gopnik

Psychologist, UC, Berkeley

The Internet has made my experience more fragmented, splintered and discontinuous. But I'd argue that's because I have mastered the Internet as an adult. So children who grow up with the Web will master it in a way that will feel as whole and natural as reading feels to us. But that doesn't mean that their experience and attention won't be changed by the Internet.

Repetition versus truth

Daniel Haun

Cognitive Anthropologist, Max Planck Institute

There is a human tendency to mistake repetition for truth. How do you find the truth on the Internet? You use a search engine, which determines a page's relevance by how many other relevant pages link to it. Repetition, not truth. Hence, the Internet does just what you would do. It isn't changing the structure of your thinking, because it resembles it.

Exaggeration

Steven Pinker

Cognitive Psychologist, Harvard University

I'm skeptical of the claim that the Internet is changing the way we think. To be sure, many aspects of the life of the mind have been affected by the Internet. Our physical folders, mailboxes, bookshelves, spreadsheets, documents, media players, and so on have been replaced by software equivalents, which has altered our time budgets in countless ways. But to call it an alternation of "how we think" is, I think, an exaggeration.

Mental Clock

Stanislas Dehaene

Neuroscientist, Collège de France

Few people pay attention to a fundamental aspect of the Internet revolution: the shift in our notion of time. Human life used to be a quiet routine that has become radically disrupted, for better or for worse. Do we aim for ever faster intellectual collaboration? Or for ever faster exploitation that will allow us to get good night's sleep while others do the dirty work? Our basic political options remain essentially unchanged.

Connecting is disconnecting

Marc Hauser

Psychologist and Biologist, Harvard University

Our capacity to connect through the Internet may be breeding a generation of social degenerates. I do not have Webophobia, greatly profit from the Internet as a consummate informavore, and am a passionate one-click Amazonian. But our capacity to connect is causing a disconnect. Perhaps Web 3.0 will enable a function to virtually hold hands with our Twitter friends.

Diminished attention

Nicholas Carr

Author

My own reading and thinking habits have shifted dramatically since I first logged onto the Web fifteen or so years ago. I now do the bulk of my reading and researching online. And my brain has changed as a result. Even as I've become more adept at navigating the rapids of the Net, I have experienced a steady decay in my ability to sustain my attention. My own experience leads me to believe that what we stand to lose will be at least as great as what we stand to gain.

Diet-Internet

Rodney Brooks

Computer Scientist, MIT

The Internet is stealing our attention. Unfortunately, a lot of what it offers is merely good sugar-filled carbonated sodas for our mind. We, or at least I, need tools that will provide us with the Diet-Internet, the version that gives us the intellectual caffeine that lets us achieve what we aspire, but which doesn't turn us into hyper-active intellectual junkies.

People Can Be Nice

Paul Bloom

Psychologist, Yale University

The proffering of information on the Internet is the extension of this everyday altruism. It illustrates the extent of human generosity in our everyday lives and also shows how technology can enhance and expand this positive human trait, with real beneficial results. People have long said that the Web makes us smarter; it might make us nicer as well.

A miracle and a curse

Ed Regis

Science writer

The Internet is not changing the way I think (nor the way anyone else thinks, either). I continue to think the same way I always thought: by using my brain, my senses, and by considering the relevant information. I mean, how else can you think? What it has changed for me is my use of time. The Internet is simultaneously the world's greatest time-saver and the greatest time-waster in history.

Every year, ideas impresario John Brockman asks one hundred super-bright minds one big question, and shares their answers with the world.

This time out, the question was about science and what big development in our lifetimes will change the world. What will change everything?

The answers — from Craig Venter, Richard Dawkins, Lisa Randall, Irene Pepperberg, and many more — range from mind-reading to space elevators to cross-species breeding. Yikes.

This hour, On Point: “This will change everything…”

You can join the conversation. Tell us what you think — here on this page, onTwitter, and on Facebook.

Guests:

John Brockman joins us from New York. He’s the founder of the Edge Foundation, which runs the science and technology websiteEdge.org. Every year, Edge asks scientists and thinkers a “big question,” and publishes the answers in a book, which Brockman edits. The latest, just out, is “This Will Change Everything: Ideas That Will Shape the Future.” It’s based on the 2009 question: “What game-changing scientific ideas and developments do you expect to live to see?” The 2010 question, “How is the internet changing the way you think?,” has just been posted.

From Cambridge, Mass., we’re joined by Frank Wilczek, Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist and professor of physics at MIT. His response to the 2009 Edge question discusses coming technological advances resulting from deeper understanding of quantum physics. He’s the author of several books on physics for the lay reader, most recently “The Lightness of Being: Mass, Ether, and the Unification of Forces.”

And from Berkeley, Calif., we’re joined by Alison Gopnik, professor of psychology and affiliate professor of philosophy at UC-Berkeley and an expert on cognitive and language development. Herresponse to the 2009 Edge question discusses the extension of human childhood. Her latest book is “The Philosophical Baby: What Children’s Minds Tell us About Truth, Love, and the Meaning of Life.”

|

|

|

il venerdi di Repubblica Science THEORY AND PRACTICE

BRAIN TRUST "Between Possible and Imaginary" is the theme of the Science Festival which opens in Rome next week. The American popularizer John Brockman collected the forecasts of the greatest living minds about ideas that will change everything during their lifetime. From DNA to education, the book illustrates surprising and provocative discoveries from the world that await us. |

|

PHOTO: FREEMAN DYSON |

|

In a photo dating back to the 1960s John Brockman appears in profile, standing between Andy Warhol, the father of Pop Art, and Bob Dylan. Born in Boston around twenty years earlier, Brockman went to New York for studying Economics at Columbia University and in those years he started to to become interested in Computer Science, Astronomy and Artificial Intelligence while attending a group of New York artists. Today he is the owner of a literary agency that represents personalities such as psychologist Daniel Goleman (author of the famous Emotional Intelligence) and the zoologist Jared Diamond, who wrote Guns, Germs and Steel, the book that introduced readers around the world to the idea that political and economic balances are historically related to biological and environmental dynamics (the book gained the author a Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction). |

|

[PHOTO: CRAIG VENTER]

[PHOTO: RICHARD DAWKINS] [PHOTO: IAN MCEWAN]

[PHOTO: BOOK JACKET—THIS WILL CHANGE EVERYTHING] |

|

[PHOTO: CHRIS ANDERSON]

[PHOTO: JOHN BROCKMAN] |

|

EVENTS Experts from different countries will take part in the Roman event dedicated to science. Where entertainment will also have a place The fifth edition of the Science Festival will start next January 13th. The theme this year is Between the possible and the imaginary. Technological magic and scientific research. The pogramme, that runs until Sunday Jan. 17th, includes debates, lectures and scientific cafés designed for different discipline and aimed at different age groups. On the first day, the virologist Ilaria Capua will discuss the relevance of scientific thought with the sociologist of science Massimiano Bucchi, while the anthropologist and geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli Sforza will animate a debate on technology scenarios with Enrico Bellone and Telmo Pievani. Experts like robot engineer Gianmarco Veruggio, Mark Cutkosky, from Stanford University, and Amir Shapiro, from the University of the Negev, Israel, will discuss robots, artificial intelligence and ethics. The schedule also includes shows like that of Wednesday 13th, by the Motel Connection, entitled "HEROIN - Return of Human Environmental Output / Input Network”. Friday January 15th and Saturday 16th astrophysicist Margherita Hack will be involved in a Concert for astrophysics and radio telescopes with an ensemble of musicians. |

Sind der Preis für Maschinen, die denken, Menschen, die es nicht mehr tun? Der Literaturagent John Brockmann hat führenden Erforschern und Entwicklern der Netzkultur die Frage gestellt, welchen Einfluss das Internet auf unser Denken nimmt. Wir dokumentieren eine vorbildliche Debatte mit eindeutiger Diagnose.

08. Januar 2010 An diesem Freitag veröffentlicht der amerikanische Literaturagent John Brockmandie Frage des Jahres 2010: Wie verändern Internet und vernetzte Computer die Art, wie wir denken? Im Kern der Diskussion steckt die Frage des Wissenschaftshistorikers George Dyson: „Sind der Preis für Maschinen, die denken, Menschen, die es nicht mehr tun?“

Brockman, der einige der wichtigsten Wissenschaftler der Gegenwart zu seinen Autoren zählt, umkreist diese Vision auf Edge.orgmit hunderteinundzwanzig Antworten. Wir drucken die interessantesten in diesem Feuilleton. Anders als in Deutschland, wo die Debatte über das Informationszeitalter noch immer ein von Interessen geprägtes Palaver über Medien ist, zielt die Edge-Debatte in die Tiefe.

Wer plant was, wo, mit welchen Mitteln?

Gerade wenn man die digitale Revolution ernst nimmt, muss man die Frage stellen, wie sehr die industrialisierte Kommunikation des einundzwanzigsten Jahrhunderts unser Denken verändern wird. Der Computerpionier Daniel Hillis beschreibt, wie selbst ein so simpler Vorgang wie die Programmierung der Uhrzeit über vernetzte Computer heute von vielen Programmierern kaum noch verstanden wird. Und er folgert, mit Blick auf Klimawandel und Finanzkrise: „Unsere Maschinen sind Verkörperungen unserer Vernunft, und wir haben ihnen eine Vielzahl unserer Entscheidungen übertragen. In diesem Prozess haben wir eine Welt geschaffen, die jenseits unseres Verstehens liegt. Fachleute diskutieren nicht mehr über Daten, sondern darüber, was die Computer aufgrund der Daten vorhersagen.“

Neurobiologische Auswirkungen permanenten Multitaskings führen, wie Nicholas Carr schreibt, zu Auslagerungen, zu immer größerer Abhängigkeit von den Rechnern. Was, wenn die Entscheidungsträger nicht mehr nur Entscheidungen über Kredite und Budgets von Rechnern abhängig machen, sondern auch solche über Lebensläufe? Das Profiling wird, nach den jüngsten Vorkommnissen in Amerika, zu einem noch wichtigeren Mittel webgestützter „Pre-crime“-Analytik: Wer plant was, wo, mit welchen Mitteln? Doch was mit Terroristen funktioniert, funktioniert auch, wie ein Blick aufCataphora.com zeigt, in Unternehmen und an Arbeitsplätzen.

Längst von der Wirklichkeit überholt

Einige der von Brockman befragten Autoren finden nicht, dass das Netz ihr Denken verändert. Andere sehen das anders. Keiner, auch keiner der Skeptiker, sehnt sich in eine Zeit vor dem Internet zurück. Aber viele machen deutlich, dass das, was wir als User erleben, in der Tat nur ein „Surfen“ ist, eine Bewegung auf der Oberfläche. Die deutsche Internet-Debatte ist auf dem Stand der neunziger Jahre. Eine digitale Avantgarde von eigenen Gnaden, die entscheiden möchte, wer dazugehört, tut so, als wäre Kommunikation im Netz nicht kinderleicht und als genügte es in einer Zeit, da selbst „Die Grauen“ im Netz unterwegs sind, einen Blog zu besitzen, um sich als Kenner auszuweisen. Das ist verständlich, weil es Politik- und Verlagsberatung verkauft, aber als angeblich progressive Haltung ist es längst von der Wirklichkeit überholt. Brockmans Jahresfrage setzt den Akkord für Fragen, die über das Dafür oder Dagegen weit hinausgehen.

Sämtliche Texte wurden aus dem Englischen übersetzt von Michael Adrian.