So who is the greatest biologist of all time? Good question. For most people it's got to be Darwin. I mean, Darwin is top dog, numero uno. He told us about evolution, he convinced us that evolution happened, and he gave us an explanation for it. I mean, there just wouldn't seem to be any competition. Okay, fine, well you might then say: Mendel. Mendel discovers transmission genetics, and that was pretty good. And I suppose then you have to go pretty far down the list to come to people like Watson and Crick, who just discovered the structure of DNA, which is just a bit of structural biology, really, a bit of biochemistry.

Okay, but who is the real top dog? For me, the answer is absolutely clear. It's Aristotle. And it's a surprising answer because even though I suppose some biologists might know, should they happen to remember their first year textbooks, that Aristotle was the Father of Biology, they would still say, “well, yes, but he got everything wrong." And that, I think, is a canard. The thing about Aristotle - and this is why I love him - is that his thought was is so systematic, so penetrating, so vast, so strange – and yet he's undeniably a scientist.

Aristotle was a student of Plato's. Around the year 347/8 BC, when he was in his late 30s, he left Athens and went to the Island of Lesvos. He scooted a bit along the Aegean Coast, and as he did so picked up a wife. We believe that she was 18 years old. We don't entirely know that for sure. We know her name was Pythias. We think she was very young because he says the best age for a man to marry is 37, the best age for a woman to marry is 18, and given that we know that Aristotle was 37 when he married, we infer that his wife was 18. He was a great man for rationalizing things.

In any event, he's 37, he's left Athens. He’s done this, incidentally, after Plato's death, and one explanation for why he left was that he’s the brightest guy in the academy, clearly a candidate for the top job, the head of the academy, but he doesn’t get it, so he up sticks and leaves. He arrives in Lesvos, the Island in the Eastern Aegean, around 345 BC.

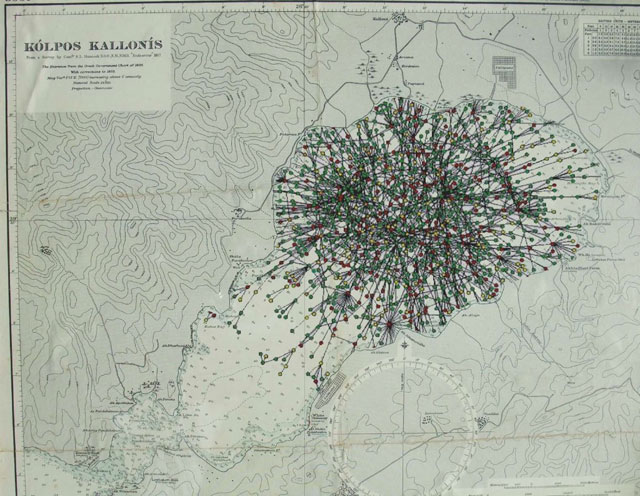

He's got his young wife, he's thinking about biology, and he goes down to the shore, and he picks up some snails, and he picks up some fish from the local fish market, and he begins to dissect them, and he writes the results down. And that's when biology is born, in those few years. I think of Lesvos, and the place that he worked, which was a lagoon, a magical lagoon, a beautiful piece of water that bisects the island, as Aristotle's Galapagos, his Down House, his Andes. It was to him what all those places were to Darwin, and to Humboldt, and all the other great biologists, each of whom seem to have some place, some location, that inspired them. And for me, that I think is what Lesvos was. What he did there was lay the foundations of biology.

We don't know the order in which he wrote his books. We can take a bit of a stab at it. Probably the first book that he wrote, though some scholars dispute this, it's not really very important, was Historia Animalium, which you can roughly call a natural history of animals. It's not really a natural history, it's certainly not a systematic treatise, rather what it is, it's a comparative anatomy. He goes through digestive systems, and hearts, and circulatory systems, and so on, and so on, and so on, and he shows how they differ between different creatures. He goes through their behavior, and he does a lot of dissections.

We've lost his book of dissections, but he refers to the dissections in there, and it's all astonishingly modern. He said, "As you can see in the picture, to the left, the part labeled "alpha" is this, and the part labeled "gamma" is that, and the part labeled "zeta" is that", and so you infer that he's got an anatomical diagram complete with labels that looks exactly like that, which you'd find in any modern textbook. Fine. So that's Historia Animalium.

Then he writes a book about the parts of animals, which is his functional anatomy. Then he writes a book about locomotion, on the movement of animals, and he writes one about sleep, and he writes another one about aging. He gives a very coherent and articulate theory of aging, which has had enormous amounts of influence right through the history of life. Indeed, it still forms part of the modern theory of aging. He writes, in fact, two books about that, and of course, he writes on generation, which is his great book about the development of animals, the generation of animals, and it's here that he does one of his great and most wonderful observations, and it's such a simple one, but it's so beautiful, and it has been so immensely influential. He takes a chicken egg, which has just been newly laid, and he opens it up, and he sees the chick embryo lying there with his little beating heart, and he watches how the chick embryo develops over the course of days. And that is the foundation of developmental biology, the science of how we make ourselves during ontogeny. And it is still to this day that chicken is used by thousands of developmental biologists.

Every generation has to reinterpret Aristotle, because the thing about him is he's so vast. His works, his biological works, would span, in small print, a shelf of books – something like that, thousands of pages. However good modern biologists may believe they are, they're nothing compared to Aristotle. No-one can compare to him in just the sheer force and scope of his thought. And that is what makes reading him so wonderful. It's a whole system of biology which bears some resemblance to our own, but is yet sort of strangely skewed by comparison because it's kind of like our biology, and yet its premises are in some ways so strange and so very different.

And that's actually what makes reading him so exciting because it causes you to look at the natural world in a way that frees you from the assumptions of modern science. You see things afresh, and you say, "Well, actually, couldn't he have a point here?" But as I said, every generation needs to read Aristotle afresh, precisely because he is so vast, and every generation finds in him the things that they are looking for. In the 19th century the big thing in science was systematic biology, it was sorting out and cataloguing the natural world. People looked at Aristotle, and they found the systematic biologist, a taxonomist. I don't know if he really was. Many scholars dispute that he was much of a classifier, and I think that's actually right. I don't think it was a primary concern of his.

So what do I find when I look at Aristotle? Well, for me the thing that fascinates me about Aristotle is his discussion of the soul. Now, I know that's a strange thing to say because when we talk about souls, we immediately think of the Judeo-Christian conception of the soul which is some strange non-physical entity that hangs above your head, or something, and survives you after death. That's not what Aristotle meant, not at all.

Aristotle thought that soul was central to life. And there's nothing vitalist about it, there is nothing metaphysical about it. It's hard to get a grip on what he meant, but it's a resolutely empirical kind of concept. What he meant was something like this: he says all living things have a soul, and when they die, the soul disappears. So none of that nonsense about the immortality of the soul. Plato thought souls were immortal, many people believed that souls were immortal, but Aristotle is clearly using soul in a very special, and technical, and new sense. It's the moving principle of life.

Okay, but what is it made of? The answer is it's not made of stuff, it's not made of matter. Well, that's a bit strange. So how can it exist if it's not made of matter? You think about that, and you think about that quite a lot, and you read Aristotle, and then you sort of see what he's getting at. What he's getting at is that the soul is not matter itself, it's the way that matter is organized. It's the relationship between the parts. It's the system. And, in fact, many Aristotelian scholars reaching for metaphors to explain what Aristotle is getting at, they use words like "system", and "cybernetic", and so on, depending on exactly when they were writing. You know, when cybernetics was cybernetics, well, they used that. And I think that's basically right.

If we understand what Aristotle is getting at, we can show, and you can find this in his text, is that he's interested in explaining how creatures take stuff from the environment, food, how they partition it, how they distribute it to the various ends that they need, and how all that is regulated by a very elaborate homeostatic system. Again homeostasis. This is cybernetics systems talk, a system that he actually tells us about in some detail. One that is deeply wrong, but then, again, his fundamental chemistry is completely barking mad by modern standards, since it’s based upon four elements. But given all that, the logic of his explanation is very clear. And it’s very beautiful.