"These are all old friends," he says.

"I've been their agent for decades. It's a wonderful life: I'm doing what I love to do, I read smart books and get well-paid for it."

The new works of his authors are next to each other in the conference room of the agency. Brockman, 73, operates out of a spacious whole floor on Fifth Avenue in New York with glass office walls and a view of the famous Flatiron Building.

These books deal with the big questions: What is man? What is the brain? What is free will? What is intelligence? And what happens when machines become smarter than humans?

Brockman likes the big issues, everything else is small talk to him.

"Man was nothing more than a model, a technique. It is necessary to construct a new model," he writes in his book Afterwords. "The human delusion lies in the belief that the human being is the basis of reality and the final goal of the evolution."

The book first appeared in 1969 under the ingenious title By the Late John Brockman and begins with the programmatic sentence: "Man is dead."

It is a small masterpiece of clear-thinking, a youthful outcry. Brockman was not even 30 at the time.

The book is aggressive, curious and prophetic and strips away the humanism of the literary mind with a Ludwig-Wittgenstein-like toughness: "The concept of freedom," he writes, "is simply absurd."

The book made him briefly known, then it was forgotten. It was too early, too radical, nobody wanted to say goodbye to humans, at least not in the literary milieu.

And now with the book published in German for the first time as Afterwords, you realize that you recognize or understand some revolutions only in retrospect 30 or 40 years later. Writes Brockman: "The past is an illusion. There is no sequence. There is no specific causality. There is merely the order and organization of the brain in a world of simultaneous operations."

These are all thoughts that are strongly influenced by cybernetics, the scientific discipline developed by Norbert Wiener in 1940s, which is a key science for an understanding of the computer age. According to Wiener, the brain is a machine, and awareness does not exist, because the information a human being receives is a mathematically realized process. We are, in other words, only part of a system, mechanisms that are part of a larger machine.

These were ideas that fascinated the artistic avant-garde in the sixties, which saw the expression of its time in the new technologies, an example of which was Nam June Paik, the video artist who demonstrated how the media-networked brain sees the world. "The composer John Cage gave me Wiener's book Cybernetics at that time," says Brockman, "and that changed everything for me. I realized that there is no reality: we create it. We create tools and recreate ourselves through our use of them. New technologies equal new perceptions. It is the tools, the technologies, which shape us, not the reverse, as people like to think.

"The book first appeared in 1969 under the ingenious title By the Late John Brockman and begins with the programmatic sentence: 'Man is dead.' ... It is a small masterpiece of clear-thinking ... aggressive, curious and prophetic and strips away the humanism of the literary mind with a Ludwig-Wittgenstein-like rigor... And now with the book published in German for the first time as Afterwords, you realize that you recognize or understand some revolutions only in retrospect 30 or 40 years later."

Brockman was then already deeply connected with the New York avant-garde scene. Jonas Mekas, the legendary filmmaker approached him in 1965, when Brockman was playing his banjo in the park. He asked if he could film Brockman, and the two got to talking, and shortly thereafter Brockman stopped working in investment banking and, with Mekas, organized the legendary "Expanded Cinema Festival," combining film with art and everything else, especially with life.

Brockman was born to Jewish parents. His father's ancestors came from Vienna and Hungary, his mother's from Vienna and Krakow. They were poor, there were no books in the house, he recalls, but "learning was everything." Like many who charge through life with the force of a electric kitchen mixer, he had been ill as a child. He was in a coma, with spinal meningitis, and it seemed his death sentence. Then he woke up and he said two things: First, "I want to go to New York." Second, "No tomatoes."

He grew up in Boston, faced with the full force of the Christian anti-Semitism, Catholic Irish in this case, that many cultivated there. "At five years old, I was punched in the face because I was personally responsible for the death of Jesus. Then my brother and I learned judo. And my mother comforted us by saying: "They have ham, we have Einstein."

Otherwise, religion played no major role in the Brockman home. While John had a Jewish religious education, "the word of God was never mentioned. Religion is alien to me. But I don't call myself an atheist because the words 'theism' and 'theist' carry no meaning for me."

He was at first a poor student and only later an excellent student, having "the best ever" semester at the small Babson College, where, says Brockman, there were supposedly 500 students with an estimated 700 cars. Foreign dictators sent their children to study there.

From Columbia University, where he studied economics, he was offered a scholarship, which he could not accept. "None of my sons takes a scholarship," said his father, by then a successful wholesale florist.

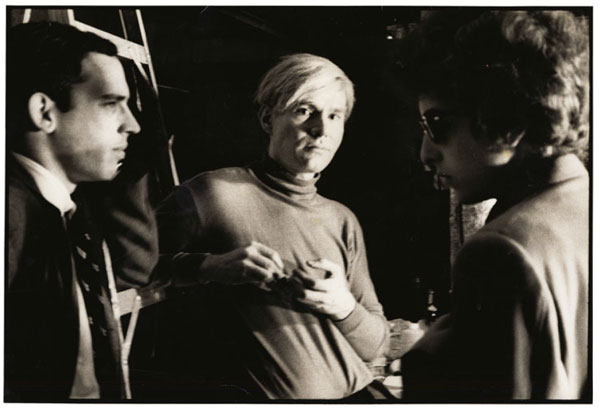

This existential hardness has transferred to Brockman and he cushions it with humor. He plunged into the cultural maelstrom of New York, Greenwich Village in the sixties, Joan Baez in the small clubs, Bob Dylan and Andy Warhol at the Factory, and in their midst, often with a fine suit and hat, the eternally curious Brockman.

New York's avant-garde Brockman, Warhol, Dylan 1965: "The concept of freedom is absurd." (NAT FINKELSTEIN) |

What the majority of people thought was never interesting to him. He did not want to be blinded by the conventions of culture or politics. He doubted that both have the meaning that man gives them. "Political considerations are irrelevant," Brockman wrote, when the whole world was talking about political considerations. "The concept of free people, the concept of free choice is no longer applicable."

A big influence on Brockman, one that led to more and more enthusiasm, was an incident involving contact with scientists that changed his world and his life: while at the New York Film Festival he received a call from Harvard, asking whether the artists he worked with would like to meet with a few scientists and see what came out of it. This moment was the birth of the third culture.

Brockman himself has called it that. His idea was a synthesis of the sciences and the humanities. In fact, it describes, rather, the victory of the hard sciences over the soft sciences. And Brockman played a central role in popularizing the science turn.

"'No democratic government,' he writes in Afterwords, 'no legislature, has ever indicated by voting, which information was desired. No one ever voted for the telephone. No one ever voted for the automobile. No one has voted for the printing press. No one ever voted for television. No one ever voted for space travel. No one ever voted for electricity.'"

Brockman has even said that his idea, a synthesis of a scientific worldview describes rather the victory of the hard sciences over the soft sciences. And Brockman had a central role in popularizing science-minded thinking.

The Harvard meeting resulted in Brockman becoming and remaining the agent of the main authors of this rapidly expanding science book market.

To him the world had changed in a way that still shapes us more than we know: The hippie spirit and the high-tech thinking allied themselves, through the use of LSD which led to the idea of an expanded consciousness or awareness as an open system. And the computer, developed in the forties in American war laboratories, became the central means of a new kind of thought, a new time, which pushes people along rather than being controlled by them.

"No democratic government," he writes in Afterwords, "no legislature, has ever indicated by voting, which information was desired. No one ever voted for the telephone. No one ever voted for the automobile. No one has voted for the printing press. No one ever voted for television. No one ever voted for space travel. No one ever voted for electricity."

It was an anti-humanist manifesto, the book "was only read very intensely or ignored," as Brockman says. "For me it's a literary work in the tradition of Ezra Pound and James Joyce. I didn't want to explain anything. I was interested in new forms of description. Why do people always expect explanations? "

Brockman regards the "the human" as a "bad idea," as he says, "which does not mean that I personally am not nice to you."

Agent Brockman with clients (David Gelernter, Brian Greene, Marc Hauser, Alan Guth, Jordan Pollack, Jaron Lanier, Lee Smolin in Connecticut 2001). What is man, what is the brain? TOBIAS Everke / AGENCY FOCUS |

Viewed from today these words have a different relevance, which is why the reading of Afterwords also is very exciting. As man slowly seems to turn into an algorithm, this is then a consequence of the cybernetic thinking that has influenced and sustained Brockman in the world.

In 1973 he founded his agency for the books of his scientist friends, in the mid-nineties he formed the Edge Foundation, which reflects the thoughts and questions of the Third Culture on a website and in annual anthologies.

Brockman, always on a mission to spread his knowledge to make science understandable, on the other hand, says: "I'm not interested in the average person. Most people have never had an idea and wouldn't recognize one if did."

Afterwords, in some ways, describes the beginning of the computer age as we know it. But what will happen, what about the worries about total transparency regarding the monitoring, the future of man, when machines become superior to us in intelligence and no longer need us?

"These are very German questions," says Brockman who has had experience with what the fear of new technology can mean: One of his friends, the computer scientist David Gelernter, was one of the 1993 victims of the Unabomber; when he received a letter bomb and was seriously injured in his right hand and right eye.

"Viewed from today these words have a different relevance, which is why the reading of Afterwords also is very exciting. As man slowly seems to turn into an algorithm, this is then a consequence of the cybernetic thinking that has influenced and sustained Brockman in the world."

Brockman does not want to talk about the Unabomber, the confused enemy of technology. "The man was just crazy," he says. But much of the fragility and vulnerability of the digital age already is contained in Afterwords. "You don't have to affirm life," he writes. "Nobody is listening to you, nobody cares about you, nobody is interested in your words."

In this respect, Brockman has been very consistent. Afterwords was the last book he wrote. ■

First published in German by Der Spiegel, Nr. 47/17.11.2014, pp138 140 (Paywall). Photo by Dirk Eusterbrock / Der Spiegel.