TALES FROM THE WORLD BEFORE YESTERDAY

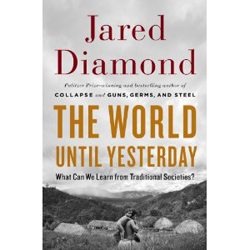

In Guns, Germs, and Steel, I set out to explain why, after the end of the last Ice Age, the most powerful and technologically advanced societies developed first in the Fertile Crescent and spread from there to Europe and North America. In Collapse, I asked why many societies disintegrated or vanished while others avoided that fate, and what lessons those varying outcomes hold for us today.

Since publication of Collapse, I have been attempting to understand the revolutionary changes in human societies and social relations brought about by the emergence of state government, after seven million years of simpler forms of organization. The differences are so profound, and we take state government as so completely natural, that I couldn't even pose the differences as questions until I had experienced them first-hand through living in New Guinea, a window on our past.

I first went to New Guinea 41 years ago to study birds and to have adventures. I knew intellectually that New Guineans constituted most of the world's last remaining "primitive peoples, who until a few decades ago still used stone tools, little clothing, and no writing. That was what the whole world used to be like until 7,000 years ago, a mere blink of an eye in the history of the human species. Only in a couple of other parts of the world besides New Guinea did our original long-prevailing "primitive" ways survive into the 20th century.

Stone tools, little clothing, and no writing proved to be only the least of the differences between our past and our present. There were other differences that I noticed within my first year in New Guinea: murderous hostility towards any stranger, marriageable young people having no role in choosing their spouse, lack of awareness of the existence of an outside world, and routine multi-lingualism from childhood.

But there were also more profound features, which took me a long time even to notice, because they are so at odds with modem experience that neither New Guineans nor I could even articulate them. Each of us took some aspects of our lifestyle for granted and couldn't conceive of an alternative. Those other New Guinea features included the non-existence of "friendship" (associating with someone just because you like them), a much greater awareness of rare hazards, war as an omnipresent reality, morality in a world without judicial recourse, and a vital role of very old people.

I've encountered myself some features of our primitive lifestyle among Inuits, Amazonian Indians, and Aboriginal Australians. Others have described such features among Kalahari Bushmen, African Pygmies, Ainus, California Indians, and other peoples. Of course, all these peoples differ from each other. New Guinea's 1,000 tribes themselves are diverse: they constitute 1,000 radically different experiments in constructing a human society. But they all share (or shared) some basic features that used to characterize all human societies until the rise of state societies with laws and government, beginning around 5,500 years ago in the Fertile Crescent and now established over the entire world.

I am once again treating a huge question about human societies, and in using methods of long-term comparative history. In this case I am placing much heavier weight on one area of the world, New Guinea. Yes, I include other parts of the world: I've already been gathering material on the Mongols, Cherokees, Zulus, and many others. But New Guinea will play a central role, as the standard of comparison. That's as it should be, because New Guinea's 1,000 languages make up 116th of all surviving languages, and because New Guinea contained by far the largest number of people and tribes still living under pre-state conditions in modem times.

The other difference is that my studies of New Guinea are based much more heavily on my personal experiences and observations, and less on publications by others. Many of my experiences in New Guinea have been intense—a sudden encounter at night with a wild man, the prolonged agony of a nearly-fatal boat accident, one broken little stick in the forest warning us that nomads might be about to catch us as trespassers ... Those stories carry a bigger message than mere exciting adventures that have shaped my outlook. They give us a first-hand picture of the human past as it has been for millions of years—a past that has almost vanished within our lifetimes, and that no one will ever be able to experience again.

I've gone from wrestling with difficult abstract questions about the structure of societies—about their rise from agricultural origins in Guns, Germs, and Steel, and about their decline or maintenance in Collapse. The abstractness of those questions forced me to work hard to put human faces on them. The New Guinea work is more passionate, personal, and from the heart.

TALES FROM THE WORLD BEFORE YESTERDAY

If You Camp Under Dead Trees, And Each Dead Tree Has A One In 1,000 Chance Of Falling On You And Killing You

I'll tell you the incident in New Guinea that had the biggest influence on my subsequent life. I was with a group of New Guineans doing a survey of birds on a mountain, and we were establishing camps at different elevations on the mountain to survey birds of different elevational ranges. We were moving from one camp up to another camp, and so I'd wanted to choose a new campsite.

I found a gorgeous campsite. It was on a place where the ridge broadened out and flattened out. It was a steep drop-off, so I could stand at that edge and look out and see hawks and parrots flying. The broad area of the ridge meant that there was going to be good bird-watching walking around there. And it was beautiful, because my proposed campsite was underneath a gigantic tree, just a gorgeous tree. I was really happy with this campsite. I told the New Guineans, "Let's make camp here."

And greatly to my surprise, they were frightened out of their minds, and they said, "We're not going to sleep here. We'll sleep out in the open, rather than sleep in tents here." I said, "What's the matter?" They said, "Look at that tree. It's dead." Okay, so I looked up, and yes, this gigantic tree was dead, but it was solid as iron. And I told them, "All right. So maybe it's dead, but it's going to stand there for another 70 years, it's so huge and solid." But no, they were just terrified, and they were not going to sleep under that dead tree. They actually did, rather than sleep under the dead tree, they went and slept 100 yards away.

We stayed at that campsite for a week and naturally, nothing happened. I thought that the New Guineans were just being paranoid.

And then, this was early in my career, as I got more experienced in New Guinea, I realized, every night I sleep out in New Guinea forest. At some time during the night, I hear the sound of a tree crashing down. And, you see tree falls in New Guinea forest, and I started to do the numbers. Suppose the chances of a dead tree crashing down on you the particular night that you sleep under it is only one in 1,000. But suppose you're a New Guinean, who's going to sleep every night in the forest, or spend 100 nights a year sleeping out in the forest. In the course of 10 years, you will have spent a thousand nights in the forest, and if you camp under dead trees, and each dead tree has a one in 1,000 chance of falling on you and killing you, you're not going to die the first night, but in the course of 10 years, the odds are that you are going to die from sleeping under dead trees. If you're going to do something repeatedly that each time has a very low chance of bringing disaster. But if you're going to do it repeatedly, it will eventually catch up with you.

That incident affected me more than anything else, because I realized that in life, we encounter risks that each time the risk is very slight. But if you're going to do it repeatedly, it will catch up with you. And ever since then, I'm now very cautious about how I stand in the shower, how I walk on sidewalks, how I go up and down stairs, how I take left turns in my car.

Most of my friends, they're just driven crazy by my caution. The friends who best understand my attitude are people who've encountered dangers themselves. A friend of mine who piloted small planes; a friend of mine who was a British bobby on the streets of London, and dealt with criminals, unarmed himself; and a friend of mine who's a river guide and has seen people drown. They understand very well why you should be ultra cautious about rare events that, each time it looks as if you're paranoid, but it will eventually catch up with you.

One Of The Stupider, More Dangerous Things That I Did In My Life

The next one has one bird. This was probably one of the most dangerous things that happened to me in New Guinea, one of the things where I came closest to getting in severe trouble. And I didn't realize it at all at the time. I wanted to cross a mountain to a site several days' walk away. And so, I set out with a bunch of 15 New Guineans who were carrying my bird-collecting equipment and my supplies, and the food for two weeks. They were a few local people, and then they were New Guineans who worked with me, who came from another area and didn't know this area.

So we started out on a trail. The first day's trail wasn't bad. The second day's trail was one of the most excruciatingly difficult trails I've done in New Guinea. It was not a trail. Instead, the second day's trail was simply wading in a river. And it was a mountain stream with big boulders. The boulders were slippery. There was no path. We had to pick our way between the boulders. At each boulder, you could fall down and slip. It was raining all day. And finally, at 4:00 we were exhausted, and we stopped and camped for the night, in the rain. We were now two days' walk from the village where we had started.

The way that we camped out was that my 15 New Guineans slept underneath a tarpaulin that I had brought along. It was an open tarpaulin with a ridgepole. The tarpaulin slung over the ridgepole, and so the tarpaulin's open at the front or the back. They slept underneath it with a fire to keep themselves warm. I had one of these Eureka green pup tents. It's a small tent with an external frame. And I placed my pup tent literally just a couple of feet away from the New Guineans' tent. These Eureka tents have a zip-up door, and a zip-up rear window. When they zip up, the front with a door, and the back with a window look completely solid green. So it looks as if the tent … you can't see any opening to the tent. You might see where the zipper is operated, but if you're not familiar with Eureka tents, you wouldn't know which is the door zipped up and which is the window. So, I was exhausted. We all went to sleep.

The door of my tent faced the New Guineans' tent. After a while, I woke up because I could feel that there were footsteps. I could feel the ground was shaking slightly with footsteps. And it was clear that someone was walking along the side of my tent, and then stopped at the end of my tent, which had the zipped-up window. It was the end of the tent away from the New Guineans' tent. I figured, okay, one of the New Guineans has gone out to relieve himself.

But it seemed strange that, why did he relieve himself coming out to my tent? Why didn't he go out the other end of his own tent, rather than relieving himself next to my tent? But, New Guineans do whatever they want, so I just went back to sleep.

And then, within a very short time, I was woken up by the sounds of my New Guineans talking, and I could see that there was a bright light. They had poked up the fire so that the fire was burning brightly, and they were talking. New Guineans often talk at night. It keeps me awake, and so I shouted out, "(inaudible- native language)." And they quieted down. That was the entire incident. There was nothing else that happened. I didn't realize there was any danger.

The next morning, when I woke up, I looked out, and there was the New Guineans in their tent. And they told me that, what had happened the previous night was that the sounds that I heard of them talking and the fire flashing up, they were asleep, and one or two of them sensed that there was some man standing there at the entrance of their tent. And they described it. They said a man was standing there, a strange man, and his arm was stretched out, and his wrist was dipping like this. They explained the significance. And he just stood there. They were frightened, because he looked intimidating, and he was a stranger to them.

So they were frightened, they shouted out, and then ran away. This was really strange, because it was a dark night. New Guineans don't wander around much at night in the forest. It was raining, and we were now two days from the nearest village. And they pointed out some footsteps, where this guy had run off. But they didn't explain anything further about it.

Okay, so strange things happen in New Guinea. I'd gotten used to the fact that unexplained things happen. So, I didn't attach any significance to it, and we went hard for the last day. This time, the weather was clear. It was a gorgeous forest. It was like walking in a cathedral with tall trees. I was walking next to a stream. It was so beautiful. But I just went ahead of the New Guineans, carrying my gear, so that the noise of them wouldn't disturb. I got far ahead of them, and I kept going on ahead until I reached a river, and then I sat down and waited for the New Guineans.

They caught up with me. We then arrived at the village where I wanted to stop, and we spent two weeks studying birds at the village. Came back. When we came back, instead of the local New Guineans taking us back by that horrid torrent they took us back by a good, clear trail. I have no idea why they exposed all of us, including themselves, to that horrible torrent.There was a good trail. For whatever reason, they didn't take us out on the one.

When we got back, I related the story of the man at night to the missionary at the site from which we had started out. And the missionary explained what it was about. He said, this was an area where, until five years previously, people had been semi-nomadic, living in the forest. And then they settled at the request of the government.

But, there was one man there … a man who was literally crazy, paranoid … who continued to live in the forest. He was a powerful sorcerer. He was dangerous. He had killed two of his wives. He had killed one of his sons. One of his young sons had eaten a banana when this crazy guy said, "Don't eat the banana." So this guy had killed his son. And he was now living alone in that area forest.

The missionary who was relating this to me, the missionary told me that this crazy guy had threatened him, poked a spear up through the floor of the house in which the missionary was sleeping, attempted to kill the missionary. But the local people were afraid of him, because he was such a powerful magician.

The significance of the guy holding out his arm, dipping at the wrist, is that that's a gesture that magicians use to imitate the cassowary. The cassowary is New Guinea's biggest bird. It's flightless. It's like a small ostrich. Weighs up to 100 pounds. And it has razor-sharp legs that can disembowel a man. The sign of the cassowary, if you hold out your arm like this, that's the cassowary rolling its head and dipping its head when it's ready to charge. So magicians will imitate a cassowary in order to show their power. Because the cassowary's big and powerful. Magicians identify with the cassowary. They intimidate people.

So, here's this crazy guy. Why did that crazy guy come into our camp at night? I don't know why he came into our camp. It's safe to assume that he saw the green tent and he knew that there must be a European inside the tent. It's safe to assume that his reasons for coming to a camp were not friendly. Probably what happened was that he walked around the tent to try to find out how to get into the tent, and he could not tell the difference between the zipped-up front door and the zipped-up rear window, and he couldn't figure out the zipper. And, then came the shouts of the New Guineans, so he ran off.

My guess is that he was there to do some mischief. The next day, when I walked around, walked on alone for several hours. In retrospect, if I had understood what this was all about … that was one of the stupider, more dangerous things that I did in my life, because it was very possibly, we were still being followed by this crazy guy. And if he had come up to me, who knows what would have happened? So, that was a case of a danger that I didn't appreciate at the time, but in retrospect, it was one of the more dangerous moments of my career in New Guinea.

How I Discovered The Long-Lost Bowerbird, Initially Without Realizing It

The discovery of the long-lost bowerbird. That was a wonderful, magical experience. The background to it is that in the 1800s, the biological exploration in New Guinea initially was not carried out by European collectors, but instead New Guineans themselves would collect birds. They'd collect birds for their own purposes, to decorate themselves with birds of paradise. And there were bird merchants based in what's now Jakarta, but it was then Batavia, the capital of Dutch New Guinea. These merchants would come out and buy bird specimens from New Guineans.

And the specimens were then sent back to Paris, because there was a huge trade in beautiful bird feathers. The beautiful birds were sold to women for decoration for their hats, but ornithologists like Lord Rothschild, who had his own private museum in Tring, in Britain, ornithologists made a deal with the hat collectors that they would first scrutinize each new shipment that came in from New Guinea to see whether there was a specimen of a bird new to science. So, that's how the birds of paradise and bowerbirds were discovered. Not by Europeans collecting them, but they turned up in Paris hat shops.

Eventually, Europeans started going out to New Guinea, and going to different parts of New Guinea, and they began finding one after another of these birds first described in hat shops.

In 1895, four specimens of a gorgeous bowerbird showed up in a Paris hat shop. It was gorgeous, because the crest of it was a beautiful yellow orange, a flaming yellow orange, and became known as the golden-crested bowerbird. It showed up in a hat shop. It was safe to assume that it was from New Guinea because other bowerbirds were from New Guinea. But there was no indication where the feather merchant had gotten it.

Gradually, over the course of the following decades, one expedition after another, from New York and from Tring and from Germany, went to different parts of New Guinea, and they began finding where individual ones of these hat shop birds came from. Some came from the Hwan Peninsula, and some came from the Sea Birkin. Some came from the Fly River. So, by the 1930s, all but two of the hat shop birds had been tracked down to their home grounds. The two that had not been tracked to the home grounds were the golden-fronted bowerbird, and a bird of paradise called Berlepsch Bird of Paradise.

So, in 1979, my first trip to Indonesia New Guinea, the Indonesian government … I was there at the invitation of World Wildlife Fund. The Indonesian government had set up national parks in other parts of Indonesia, and they were now ready to design a national park system for Indonesia New Guinea. Hundred and fifty thousand square miles, a lot of it unexplored.

The Indonesian government told World Wildlife, "So, here's this guy, Jared Diamond, who's come to work for you. Here's a thousand dollars. Let him spend a couple of weeks running around Indonesia New Guinea, getting to know our province. And at the end of one month, we want a national park plan for all of Indonesia New Guinea. Because, at the end of a month, we are going to make the decisions about, where are that national parks and where are the mines and where are the forest projects?" So I've got a month and a thousand dollars to develop a national park plan for this huge wilderness.

The largest unexplored mountain range in Indonesia New Guinea was the Foja ... Foja Mountains. And so, I used my thousand dollars to rent a helicopter. They're very remote. There's no way you can walk into them. As far as I know, nobody has walked into them. The only way to get into them was by helicopter. Now, I knew about the long-lost bowerbird, so I thought, these are the biggest unexplored mountain ranges. Maybe this is where I'm going to discover the long-lost bowerbird.

So, I want the helicopter to drop me as high as possible on the mountain, because the bowerbird is a mountain bird, and if I got dropped high, if the bowerbird is anywhere, it's going to be high up. The helicopter took in me with one New Guinean. I wanted the helicopter to drop me as high as possible.

With a helicopter, you need to find a clearing. Unless you're really trained, you can't drop down through the canopy. So, it's a matter of finding a clearing, but there aren't many clearings in the New Guinea jungle. Fortunately, at 5,000 feet, we found a clearing.

So, we found this marsh at 5,000 feet, which would be perfect for the helicopter to land in. The helicopter spiraled down into the marsh, and the pilot realized that it was wet and muddy and that he couldn't land there. And I could see birds flying past. Here's 5,000 feet. If anywhere, this is where the bowerbird is going to be. But we couldn't land, and I was just crushed.

We took off with the helicopter, tried to find some other landing place as high. We couldn't. The only other landing place we could find was a stream bed at 1,500 feet. We landed in the stream bed. The helicopter dropped off me and a New Guinean, left us with food for a week and said, "I'm coming back in a week." If the helicopter hadn't come back, I wouldn't be here. There was no way of walking out.

So, the New Guinean with me made a trail up as high as we could go. He managed to get a trail up to 4,600 feet. I bird-watched there every day. It was utterly magical, because this is an uninhabited range. The birds were tame. The tree kangaroos were tame. I was there alone. It was just me and the mountain. I followed the same trail every day. It was one of the most beautiful experiences I've had in my life in New Guinea.

I knew that it was probably too low for the bowerbird. On the day which I got to the highest elevation, I looked up, and there, over my head, was a bowerbird of this group, the Amblyornis bowerbirds. Oh my God, here's the bowerbird. And then it tipped its head, and I saw that the crest was not golden orange, but it was reddish orange. Phooey. That's the ordinary … there's an ordinary bowerbird, McGregor's bowerbird, with a reddish-orange crest. If McGregor's bowerbird is here, for sure the long-lost golden bowerbird is not going to be here. So we forget about the long-lost bowerbird.

I had a wonderful week. The helicopter picked me up. And, a year and a half later, I came back in order to do a complete exploration of the mountain range. When I came back, the copter pilot came in with another pilot and they brought along plywood. So they came to the marsh at 5,000 feet. One, the copilot jumped out into the marsh, waded over to the edge of the marsh. He had a chain saw. He cut down some trees, put down the trees in the marsh, put the plywood down there, so the plywood was now a helipad. The helicopter could land on this helipad. Went back and picked me up and picked up three New Guineans, came back, landed us in the marsh, and left us there for two weeks.

Again, beautiful two weeks. The three New Guineans made trails. I walked around. They were tame tree kangaroos. I encountered lots of birds, and I found bowerbirds, with bowers. But the bowerbirds, they didn't have a golden orange crest. They had a reddish-orange crest. So it's, oh, this is the normal McGregor's bowerbird.

At the end of two weeks, the helicopter came and picked us up, and eventually, I went to the American Museum of Natural History to check specimens of bowerbirds. I looked at the specimen of the long-lost bowerbird, and McGregor's bowerbird. I said, oh my God. The bowerbird in the Foja Mountains, after all, it was the long-lost bowerbird. What I hadn't realized is that, when these bowerbirds die, the crest changes color. So, if it starts out red-orange, it fades with time in the museum to golden. The indication that the bowerbird that I saw was the long-lost bowerbird was the form of the crest, going up onto the forehead, and an obscure hood on it, and the form of the tail.

So, that was how I discovered the long-lost bowerbird. Even though I didn't realize at the time it was the long-lost bowerbird, I observed the mating display. The bird was tame, so I stood right there at the bower. The bird came in. It had decorated its bower with blue fruits. Picked up the blue fruits. Held the blue fruit in front of its crest, shook its head with me standing there making noise, which I recorded.

More recently, Conservational International sent an expedition funded by National Geographic that went in, again by helicopter. And they got lots of photographs of the bowerbird, and they took recordings of the bowerbird. They made a study of the mating display, and they had an article in National Geographic.

So that's how I discovered the long-lost bowerbird, initially without realizing it. But then once I realized it, I announced it. That's my best-known single discovery in ornithology.