The paradox of modern neuroscience is that the one reality you can't describe as it is presently conceived is the only reality we'll ever know, which is the subjective first person view of things. Even if you can find the circuit of cells that gives rise to that, and you can construct a good causal demonstration that you knock out these circuit of cells, and you create a zombie; even if you do that... and I know Dennett could dismantle this argument very, very quickly ... there's still a mystery that persists, and this is the old brain-body, mind-body problem, and we don't simply feel like three pounds of meat.

INTRODUCTION

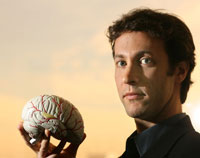

"I always thought of myself as a scientist," says Jonah Lehrer "and then I had the privilege of working for several years in the lab of Eric Kandel as a technician, doing the manual labor of science, and what I discovered there was that I was a terrible scientist. As much as I loved the ideas, I excelled at experimental failure, I found new ways to make experiments not work. I would mess up PCRs, add the wrong buffers, northerns, westerns, southerns. I would make them not work in quite ingenious ways, and I realized slowly, over the course of those years, that the secret to being a great scientist is to love the manual labor of it." But there are many ways to contribute to the conversation that is science, and Lehrer is making important contributions as a writer who has internalized the process of the scientific method in asking interesting questions about ourselves and the world around us.

"Neuroscience has contributed so much in just a few decades to how we think about human nature and how we know ourselves," he says. "But how can we take that same rigor, which has made this research so valuable and, at the same time, make it a more realistic representation of what it's actually like to be a human. After all, we're a brain embedded in this larger set of structures."

"You can call it culture, call it society, call it your family, call it your friend, call it whatever it is. It's the stuff that makes people sign onto their Facebook a thousand times a day. It's the reason Twitter exists. We have got all these systems now that really make us fully aware of just how important social interactions are to what it is to be human. The question is, how can we study that? Because that, in essence, is a huge part of what's actually driving these enzymatic pathways in your brain. What's triggering these synaptic transmissions and these squirts of neurotransmitter back and forth is thoughts of other people, what other people say to us, interacting with the world at large. " Read on...

— John Brockman

JONAH LEHRER, Contributing Editor at Wired and the author of How We Decide and Proust Was a Neuroscientist, has written for The New Yorker, Nature, Seed, The Washington Post and The Boston Globe.

Jonah Lehrer's Edge Bio Page