The question becomes, is it possible to set up a system for learning from history that's not simply programmed to avoid the most recent mistake in a very simple, mechanistic fashion? Is it possible to set up a system for learning from history that actually learns in our sophisticated way that manages to bring down both false positive and false negatives to some degree? That's a big question mark.

Nobody has really systematically addressed that question until IARPA, the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Agency, sponsored this particular project, which is very, very ambitious in scale. It's an attempt to address the question of whether you can push political forecasting closer to what philosophers might call an optimal forecasting frontier. That an optimal forecasting frontier is a frontier along which you just can't get any better.

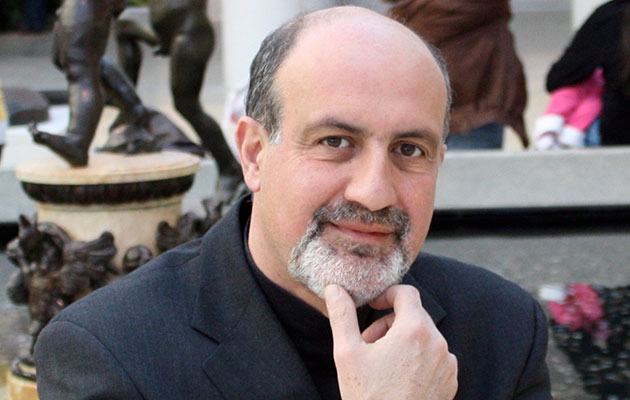

PHILIP E. TETLOCK is Annenberg University Professor at the University of Pennsylvania (School of Arts and Sciences and Wharton School). He is author of Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know? Philip Tetlock's Edge Bio Page

[46.50 minutes]

INTRODUCTION

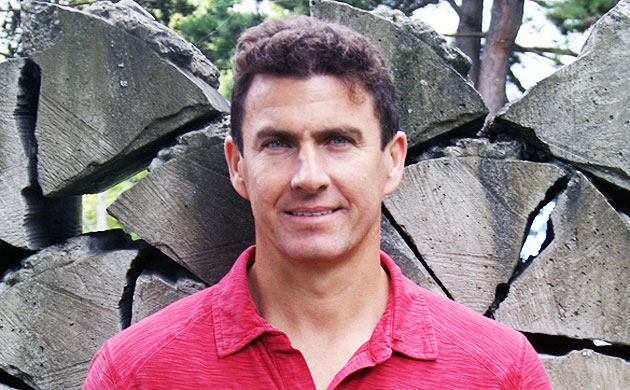

by Daniel Kahneman

Philip Tetlock’s 2005 book Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know? demonstrated that accurate long-term political forecasting is, to a good approximation, impossible. The work was a landmark in social science, and its importance was quickly recognized and rewarded in two academic disciplines—political science and psychology. Perhaps more significantly, the work was recognized in the intelligence community, which accepted the challenge of investing significant resources in a search for improved accuracy. The work is ongoing, important discoveries are being made, and Tetlock gives us a chance to peek at what is happening.

Tetlock’s current message is far more positive than his earlier dismantling of long-term political forecasting. He focuses on the near term, where accurate prediction is possible to some degree, and he takes on the task of making political predictions as accurate as they can be. He has successes to report. As he points out in his comments, these successes will be destabilizing to many institutions, in ways both multiple and profound. With some confidence, we can predict that another landmark of applied social science will soon be reached.

Daniel Kahneman, recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics, 2002, is the Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology Emeritus at Princeton University and author of Thinking Fast and Slow.

HOW TO WIN AT FORECASTING

A Conversation with Philip Tetlock

There's a question that I've been asking myself for nearly three decades now and trying to get a research handle on, and that is why is the quality of public debate so low and why is it that the quality often seems to deteriorate the more important the stakes get?

About 30 years ago I started my work on expert political judgment. It was the height of the Cold War. There was a ferocious debate about how to deal with the Soviet Union. There was a liberal view; there was a conservative view. Each position led to certain predictions about how the Soviets would be likely to react to various policy initiatives.