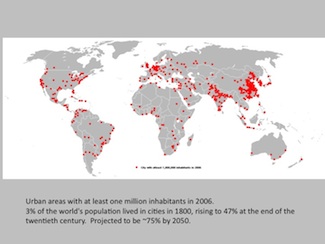

But by 2005, we've passed a milestone in our history, in that 50 percent of humanity, 50 percent of all human beings, lived in cities by 2005. And the projection is that by 2050, three out of every four of us will live in cities around the world. And so images like this will become the norm, rather than the visions of Arcadia. And already we can make a plot of cities around the world of more than a million inhabitants. And that figure's only going to get larger and larger. And already the world at night reflects this movement to urbanization.

|

|

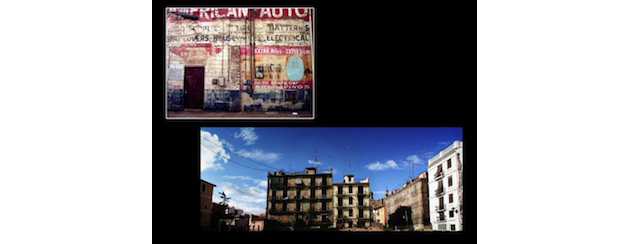

And visions like this, of Calcutta, are commonplace. Swarms of people living in these urban areas. Very, very different from our vision of Arcadia and our vision of our original garden. Images like this are also becoming more and more common, these vast high-rise towers.

But so are images like this. Or images like this. And so we really want to understand why this impulse arose. Why is it that we went from this sort of vision of Arcadia, one vision of Arcadia, to this?

Now, one answer we can give to this is a metaphorical one, a figurative one. And we might say that cities somehow allow us to mingle our obvious love of nature with the sort of human-built environment. This love of nature that must be hard-wired into our DNA with the human-built environment. Somehow there's a joy we get out of that. And sure enough, cities are figurative gardens, aren't they?

If we look around the world, we don't have to look very far to see the garden intruding on our cities, in some sense. Beautiful gardens within cities. And of course right here in Hyde Park, one of the most lovely gardens we can imagine within a city. And yet, this lovely metaphorical, almost poetic description of why we've moved to cities somehow falls way short of the mark. Because we know that as soon as human beings started moving into cities, just 10,000 years ago, they suffered from two brand-new forms of predation.

The first form of predation they suffered from was from people who wanted to sack and plunder the cities they'd built. So if we go into the archeological record, we see that as soon as humans started making cities, they started building defensive walls around them. And we could say that one of the greatest stories in all of Western literature, Homer's "Iliad," is really the story of a city with a very thick defensive wall. One that took ten years for the Greeks to breach.

The second form of predation, though, wasn't predation from without; but predation from within. Because as soon as we moved into cities, we suffered from the plagued and pestilences of diseases that could fester among those high-density populations. Remember that by 10,000 years ago, we already had six, seven, 8,000 people living in these little villages like Catalhoyuk. And so we somehow have to overcome all of the disadvantages of living in cities, these forms of predation. And there's also thievery within, wasn't there?

And so it's not enough to merely give a figurative description. But it turns out we have an answer in the cities, because cities are much more than figurative gardens. It turns out that throughout our history, cities are actually literal gardens of human prosperity. They are the crucible of human civilization.

And the reason that cities have acted as these gardens for innovation and prosperity, is really down to three things that we can document. And those of you living in London, this won't come as completely a surprise. One is it's easy to show that cities have been historically magnets for creative people, innovative people, entrepreneurial people, wealth creators. They've been a magnet for that throughout our history.

Social scientists and complexity theorists who study how cities grow are able to document that as cities increase in size, various things about cities go up faster than the rate of population growth. Things that are good. And so it's know that as cities increase in size, the number of innovations increases faster than population growth. The number of new patents increases faster than population growth. Wages go up faster than population growth. Standard of living rises than population growth. All because cities have always attracted the creative entrepreneurial, innovative types. They've been magnets for them.

And it's even the case that cities are more efficient than groups of people living in the countryside. So that cities, in some sense, are being touted as the new green centers of humanity. And here's why: as these good things increase faster than the rate of population growth, things that we might think of as bad about cities increase slower than the rate of population growth. So a city the size of London has fewer roads per capita than a city the size of Manchester or a city the size of Oxford or a city the size of Redding. It has fewer sewers per capita. It uses less heat per capita. It has fewer cables per capita.

And so good things increase faster than the rate of population in big cities, and bad things increase at a slower rate. Cities are more efficient. So even though a huge city like London belches out enormous amounts of pollution, if you broke up London into a whole lot of smaller villages or towns with equal population, it would contribute far more pollution. And so, in some sense, cities are the green centers of humanity.

But there's a catch. It all sounds too good to be true. It is; there is a catch. And that is, cities have to continually reinvent themselves to avoid this sort of thing, social and physical collapse. They have to reset their carrying capacity to be able to accommodate the increasing density of people. But for the reasons I've given you, they've been very, very good at that.

And so we can realize that over time, what have cities done? Well, they've invented clean water, they've invented sewer systems. They've cleaned up their air, they've invented telephones. They've invented roads. All of these things make it easier for large numbers of people to live in these small environments. And we can see this going on and on. We've invented the Internet and who knows what will come next.

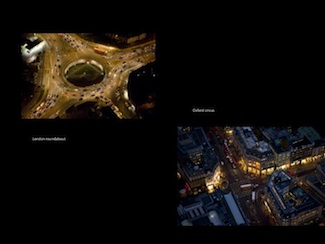

And so for the very reasons that cities have been magnets for creative and innovative people, they've been able to reset their carrying capacity over time, and largely avoid this sort of social and physical collapse. And so here's just a few pictures of the sort of things cities are good at. These are all biased toward transport, I'm afraid, but I've mentioned to you the other things like clean water and clean air and sewers and roads and so on, telephone exchange. Inventing subway systems. And of course, we're all very affectionate about Boris' bike scheme.

|

|

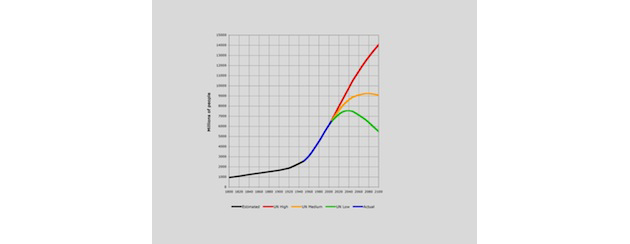

And so as we look to the future, we realize that somehow we're going to have to accommodate what looks like a lot more people on this planet. Here are three population projections to the end of this century. And the middle one, the golden one, is the one that most people accept now, and even it suggests that the six billion people we have on this planet now are going to rise to maybe nine billion people by 2050.

And so using this idea of the city as a garden, we realize that to save our planet, these cities are going to be the true gardens of the 21st century, to accommodate all these people. And so we're going to have to cultivate places like this if we want to be able to survive our growth into the 21st century. Thank you.