Edge in the News

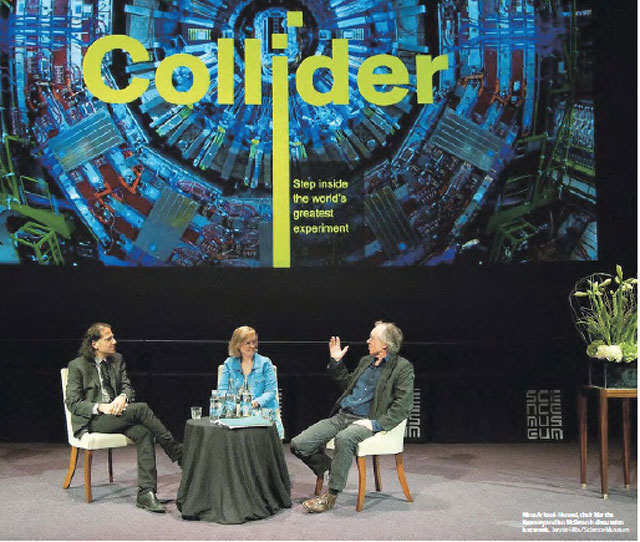

Novelist Ian McEwan and theoretical physicist Nima Arkani-Hamed met at the Science Museum in London to mark the opening of the Large Hadron Collider exhibition. This is an edited extract of their conversation.

DO THE TWO CULTURES STILL EXIST?

IAN McEWAN: That old, two-culture matter is still with us, ever since [CP] Snow promulgated it back in the 50s. It still is possible to be a flourishing, public intellectual with absolutely no reference to science but it's happening less and less. And I think it's less a change of any decision in the culture at large, just a social reality pressing in on us. And it's true that climate change forces us to at least get a smattering of some idea of what it is to predict systems that have more than two or three variables and whether this is even possible. The internet has created sites like John Brockman's wonderful edge.org, where it's possible for laymen to sit in on conversations between scientists. And when scientists have to address each other out of their specialisms they have to speak plain English, they have to abandon their jargons, and we're the beneficiaries of that.

NIMA ARKANI-HAMED: It's an asymmetry that doesn't really need to exist. Certainly many scientists are very appreciative of the arts. The essential gulf is one of language and especially in theoretical physics, the basic difficulty is that most people don't understand our language of mathematics which we use to describe everything we know about the universe. And so while I'm capable of listening to and intensely enjoying a Beethoven sonata or an Ian McEwan novel it can be more difficult for people in the arts to have some appreciation for what we do. But at a deeper level there's a commonality between certain parts of the arts and certain parts of the sciences. ... MORE

Nima Arkani-Hamed, Martha Kearney and Ian McEwan at London's Science Museum Photograph: Jennie Hills/Science Museum

[EDITOR'S NOTE: Related reading on Edge: "The Third Culture", 1991]

Novelist Ian McEwan in a lively conversation with theoretical physicist Nima Arkani-Hamed in an exploration of the similarities, differences and connections between art and science. This discussion is part of the opening of the Large Hadron Collider exhibition at the Science Museum in London. Arkani-Hamed is a winner of the Fundamental Physics Prize.

[IAN MCEWAN:] ...That old two culture matter is still with us. Ever since Snow promulgated it back in the '50s, it still is possible to be a flourishing public intellectual with absolutely no reference to science. It still can go on but it's happening less and less and I think it's less a change of any decision in the culture at large, just a social reality pressing in on us.

It was touched on just briefly earlier this evening that bioethics is now a critical matter. We all carry around with us miraculous tiny machines that involve at least some passing admiration for the engineering that created them. It's true also that climate change forces those of us who have no interest in science to at least get a smattering of some idea of what it is to predict systems that have more than two or three variables and whether this is even possible. So, I think it's been borne in on us.

For example, the Internet has created in sites like John Brockman's wonderful site, edge.org, where it's possible for laymen to sit in on conversations between scientists and when scientists have to address each other out of their specialisms they have to speak a lingua franca of plain English. They have to abandon their jargons. And we're the beneficiaries of that. ...

[EDITOR'S NOTE: Related reading on Edge: "The Third Culture", 1991]

Every year, intellectual impresario and Edge editor John Brockman summons some of our greatest thinkers and unleashes them on one provocative question, whether its the single most elegant theory of how the world works or the best way to enhance our cognitive toolkit. This year, he sets out on the most ambitious quest yet, a meta-exploration of thought itself: Thinking: The New Science of Decision-Making, Problem-Solving, and Prediction (public library) collects short essays and lecture adaptations from such celebrated and wide-ranging (though not in gender) minds as Daniel Dennett, Jonathan Haidt, Dan Gilbert, and Timothy Wilson, covering subjects as diverse as morality, essentialism, and the adolescent brain.

Thinking is excellent and mind-expanding in its entirety. Complement it with Brockman's This Will Make You Smarter: New Scientific Concepts to Improve Your Thinking, one of the best psychology books of 2012.

—Maria Popova, Brain Pickings

In the excellent collection This Explains Everything, edited by John Brockman, two of the contributors provide an explanation for why this is easier said than done. David M Eagleman, a neuroscientist at Baylor College of Medicine, writes of "overlapping solutions", where the brain is not made up of separate parts that deal with different activities – ie. one area for language, another for face recognition etc. Instead, he says: "The deep and beautiful trick of the brain is more interesting. It provides multiple, overlapping ways of dealing with the world."

This is echoed by the psychology researcher Judith Rich Harris, who explains that this is the root reason for a good deal of the drama in our lives and our literature, movies, plays and soap operas. It is what leads one part of us to do something that another part of us knows is wrong.

What ideas have changes in the Netherlands, or will in the future? Around 100 thinkers give their views in the recently published 'The Netherlands in Ideas'. Sprout presents a few contributions.

Netherlands in ideas http://www.mavenpublishing.nl/boeken/nederland-in-ideeen/ is the first book of a series that Maven Publishing will publish each year with around 100 leading Dutch thinkers asking for short and sweet answer to one central question about the interface between science and society. The compilers, virologist Mark G and geneticist Tim van Opijnen, have copied a bit of the art of Edge.org http://www.edge.org , because it was high time for a Dutch counterpart. The question for the first edition: 'What idea, insight or innovation in the Netherlands has changed-or will so in the future?

The question has been answered by scientists, politicians, writers, journalists, and entrepreneurs.

THE THIRD CULTURE

...Science and science fiction work on different principles. You could not have the science to say Hey, I found this an important thing about the functioning of neurons in the brain that made me really sad! That would defeat the validity of the findings. Science is objective and devoid of emotion, and art relies on emotion. I respect science and scientists, as well as scientific discourse, and I could hardly say that the same person who writes a short story about landing on the moon also can build a machine that can really do that. But doesn't fiction sometime provide you with an idea that science later follows, such as in the case of a landing on the moon, first described in the novels of Jules Verne?

---Yes, it happens sometimes. Some things actually enter into the public discourse, even the scientific conversation, such as Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, which today has become a common noun and is used in all areas of life. There is also the other side, like a web page on the Third Culture (Third Culture), led by John Brockman, where scientists put their findings into a social context, represent them through their writings, talk about the possible positive and negative impacts, the moral implications. ...

...university President Jo Ann Gora explored the FFRF’s complaint and determined that intelligent design should not be taught in sciences classes, as it is not embraced by the scientific community as holding valid theoretical value.

The author of "The God Delusion" and "An Appetite for Wonder" doesn't care for "Pride and Prejudice": "I can't get excited about who is going to marry whom, and how rich they are."

What's the best book you've read so far this year?

I've been reading autobiographies to get me in the mood for writing my own and show me how it's done: Tolstoy (at one time my own memoir was to have been called, at my wife's suggestion, "Childhood, Boyhood, Truth"); Mark Twain; Bertrand Russell; that engaging maverick Herb Silverman; Edward O. Wilson, elder statesman of my subject. But the best new book I have read is Daniel Dennett's "Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking." A philosopher of Dennett's caliber has nothing to fear from clarity and openness. He is out to enlighten and explain, and therefore has no need or desire to language it up like those obscurantist philosophers, often of "Continental" tradition, for whom obscurity is valued as a protective screen, or even admired for its own sake. I once heard of a philosopher who gushed an "Oh, thank you!" when a woman at a party said she found his book hard to understand. Dennett is the opposite. He works hard at being understood, and makes brilliant use of intuition pumps (his own coining) to that end. The book includes a helpful roundup of several of his earlier themes, and is as good as its intriguing title promises.

Who are your favorite contemporary writers and thinkers?

I've already mentioned Dan Dennett. I'll add Steven Pinker, A. C. Grayling, Daniel Kahneman, Jared Diamond, Matt Ridley, Lawrence Krauss, Martin Rees, Jerry Coyne — indeed quite a few of the luminaries that grace the Edge online salon conducted by John Brockman (the Man with the Golden Address Book). All share the same honest commitment to real-world truth, and the belief that discovering it is the business of scientists — and philosophers who take the trouble to learn science. Many of these "Third Culture" thinkers write very well. (Why is the Nobel Prize in Literature almost always given to a novelist, never a scientist? Why should we prefer our literature to be about things that didn't happen? Wouldn't, say, Steven Pinker be a good candidate for the literature prize?)

An organization promoting intelligent design is asking that Ball State review four professors teaching honors science courses.

...I could not agree more regarding the perverse effects that postmodernism has had on the humanities: tons of crappy theories, bad arguments, superficial historical recollections, paranoid political interpretations of major novels, untenable positions on basic biological facts, etc., all of which have been produced over the past 25 years or so in the name of a dubious ideological agenda of "debunking" the deeply concealed motivations of the 'truth-producers', whose shameful aim is to serve the interests of powerful groups.

But the humanities are not just that. It is difficult to define exactly what a scholar in the humanities – or an "intellectual" (at least in the French and Italian sense) – is in contrast to a scientist, but it is clearly a different job. Let us try to identify some of the differences, a bit like in those 'spot the difference' puzzles, where kids have to find a number of variations between two images that initially seem exactly the same. ...

Why communicate?

Although the foundation of every innovation is the desire to improve human life, progress is often experienced as a relentless horde of "barbarian invasion" (definition by Alessandro Baricco) that triggers feelings of powerlessness and mistrust . This is due to our inability to understand the phenomenon in progress, difficulties arising, in turn, by a double communicative deficits. On the one hand, in fact, it lacks an effective dialogue between the community of innovators and all of us. To innovate is not enough to enter service in the social fabric: it is essential to a "third culture" (John Brockman - www.edge.com), an approach such that all the protagonists of this paradigm shift meet in opportunities for debate. It is necessary that scientists comparing their case, their ideas and expectations in dialogue with us, avoiding the accumulation of knowledge in intellectual circles, encouraging the involvement of the younger generation, ensuring the succession of ideas, assessing the risks and issues related to 'advanced technology. Only by reconciling the scientific with the humanistic sphere, making the knowledge democratic, unified and accessible you can understand the meaning and direction of flow of innovations.

Why communicate?

Although the foundation of every innovation is the desire to improve human life, progress is often experienced as a relentless horde of "barbarian invasion" (definition by Alessandro Baricco) that triggers feelings of powerlessness and mistrust . This is due to our inability to understand the phenomenon in progress, difficulties arising, in turn, by a double communicative deficits. On the one hand, in fact, it lacks an effective dialogue between the community of innovators and all of us. To innovate is not enough to enter service in the social fabric: it is essential to a "third culture" (John Brockman - www.edge.com), an approach such that all the protagonists of this paradigm shift meet in opportunities for debate. It is necessary that scientists comparing their case, their ideas and expectations in dialogue with us, avoiding the accumulation of knowledge in intellectual circles, encouraging the involvement of the younger generation, ensuring the succession of ideas, assessing the risks and issues related to 'advanced technology. Only by reconciling the scientific with the humanistic sphere, making the knowledge democratic, unified and accessible you can understand the meaning and direction of flow of innovations.

...The scientists of the third culture are able to transform knowledge into words and arguments palatable to an audience much broader than just a handful of professors at some universities. The audience for these scientists write is worldwide. And it is quite natural, because who would not want to know what moves to Earth, why we enjoy sex, what are the laws that govern nature, whether born or we do, why we think what we think, why we behave as we do, if there is freedom, if there is a god, if there is a soul, and so on. All these are questions not unlike what other philosophers and writers tried to answer, but the difference is in the approach: science. ...

...Along with the efficiencies and clever new applications that Big Data has yielded come big concerns about privacy. As science historian George Dyson noted in a recent article published in Edge.org, "If Google has taught us anything, it is that if you simply capture enough links, over time, you can establish meaning, follow ideas, and reconstruct someone's thoughts. It is only a short step from suggesting what a target may be thinking now, to suggesting what that target may be thinking next."

...Here's an easy prediction: Big Data is only going to get bigger. Every year, more sensors will produce more signals that will be more quickly analyzed. This will lead to more convenience. And more concern. Mr. Dyson – whose physicist father, Freeman Dyson, grappled with wondrous but fraught technologies such as nuclear energy – sums up the Big Data revolution this way: "Yes, we need big data, and big algorithms – but beware."

How are the publishing houses sure halfway through 2013?

Non-fiction publishing houses Vantilt and Maven are both strongly up in the first half. ... " We're up 50 percent," says Sander Ruys, publisher of the young nonfiction Maven Publishing house. "Now it is true that we are a small publishing house, so if a few titles do well, we notice that right away. This Explains Everything, ed. by John Brockman, published in March, has sold 4,200 units sold. "Moreover, it is our first listing in the "Bestseller 60". It just opened at #57. " ... Ruys explains the success: "Our network is growing and we are still being discovered by journalists and booksellers who then enthusiastically set to work with us. On the other hand we know ourselves better and better which titles are doing well. Furthermore Maven's community is taking shape, thanks to the hiring of new employees. in early 2013 "The pre-read club grows, where people ahead of time reading our books and discuss. Our strategy is to grow a lively community where people speak about human behavior."

[ED.NOTE: Steven Pinker, one our most important public intellectuals, has written a brilliant and imporant essay "Science Is Not Your Enemy", published today in The New Republic. "Though science is beneficially embedded in our material, moral, and intellectual lives," he writes, "many of our cultural institutions, including the liberal arts programs of many universities, cultivate a philistine indifference to science that shades into contempt. Students can graduate from elite colleges with a trifling exposure to science. They are commonly misinformed that scientists no longer care about truth but merely chase the fashions of shifting paradigms. A demonization campaign anachronistically impugns science for crimes that are as old as civilization, including racism, slavery, conquest, and genocide." ...

... "One would think that writers in the humanities would be delighted and energized by the efflorescence of new ideas from the sciences. But one would be wrong. Though everyone endorses science when it can cure disease, monitor the environment, or bash political opponents, the intrusion of science into the territories of the humanities has been deeply resented. Just as reviled is the application of scientific reasoning to religion; many writers without a trace of a belief in God maintain that there is something unseemly about scientists weighing in on the biggest questions. In the major journals of opinion, scientific carpetbaggers are regularly accused of determinism, reductionism, essentialism, positivism, and worst of all, something called “scientism.” The past couple years have seen four denunciations of scientism in this magazine alone, together with attacks in Bookforum, The Claremont Review of Books, The Huffington Post,The Nation, National Review Online, The New Atlantis, The New York Times, and Standpoint. ... — JB]

SCIENCE IS NOT YOUR ENEMY: An Impassioned Plea To Neglected Novelists, Embattled Professors, And Tenure-Less Historians

by Steven Pinker

"The great thinkers of the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment were scientists. Not only did many of them contribute to mathematics, physics, and physiology, but all of them were avid theorists in the sciences of human nature. They were cognitive neuroscientists, who tried to explain thought and emotion in terms of physical mechanisms of the nervous system. They were evolutionary psychologists, who speculated on life in a state of nature and on animal instincts that are “infused into our bosoms.” And they were social psychologists, who wrote of the moral sentiments that draw us together, the selfish passions that inflame us, and the foibles of shortsightedness that frustrate our best-laid plans.

The disclosures of former CIA contractor Edward Snowden, who this week was granted temporary refugee status in Russia, suggest that the government has spent years tapping the very thoughts of Internet users, as George Dyson puts it in a recent essay on Edge.org.