![]()

On July 24, 2009, a small group of scientists, entrepreneurs, cultural impresarios and journalists that included architects of some of the leading transformative companies of our time (Microsoft, Google, Facebook, PayPal), arrived at the Andaz Hotel on Sunset Boulevard in West Hollywood, to be offered a glimpse, guided by George Church and Craig Venter, of a future far stranger than Mr. Huxley had been able to imagine in 1948.

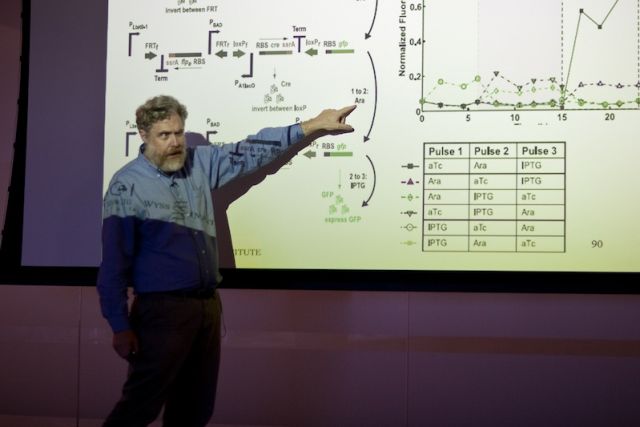

In this future — whose underpinnings, as Drs. Church and Venter demonstrated, are here already — life as we know it is transformed not by the error catastrophe of radiation damage to our genetic processes, but by the far greater upheaval caused by discovering how to read genetic sequences directly into computers, where the code can be replicated exactly, manipulated freely, and translated back into living organisms by writing the other way. "We can program these cells as if they were an extension of the computer," George Church announced, and proceeded to explain just how much progress has already been made. ...

—George Dyson, from The Introduction

Edge Master Class 2009

George Church & J. Craig Venter

The Andaz, Los Angeles, CA, July 24-6, 2009

AN EDGE SPECIAL PROJECT

GEORGE CHURCH, Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School and Director, Center for Computational Genetics, and Science Advisor to 23 and Me, and J. CRAIG VENTER, Founder of Synthetic Genomics, Inc. and President of the J. Craig Venter Institute and the J. Craig Venter Science Foundation, taught the Edge Master Class 2009: "A Short Course In Synthetic Genomics" at The Andaz Hotel in West Hollywood, the weekend of July 24th-26th. On Saturday the 25th the class traveled by bus to Space X near LAX, where Sessions 1-4 were taught by George Church. On Sunday, the Class was held at The Andaz in West Hollywood. Craig Venter taught Session 5 and George Church taught Session 6. The topics covered over the course of a rigorous 2-day progam of six lectures included:

What is life, origins of life, in vitro synthetic life, mirror-life, metabolic engineering for hydrocarbons & pharmaceuticals, computational tools, electronic-biological interfaces, nanotech-molecular-manufacturing, biosensors, accelerated lab evolution, engineered personal stem cells, multi-virus-resistant cells, humanized-mice, bringing back extinct species, safety/security policy.

The entire Master Class is available in high quality HD Edge Video (about 6 hours).

The Edge Master Class 2009 advanced the themes and ideas presented in the historic Edge meeting "Life: What A Concept!" in August 2007.

GEORGE M. CHURCH is Professor of Genetics, Harvard Medical School; Director, Center for Computational Genetics; Science Advisor to 23andMe.

With degrees from Duke University in Chemistry and Zoology, he co-authored research on 3D-software & RNA structure with Sung-Hou Kim. His PhD from Harvard in Biochemistry & Molecular Biology with Wally Gilbert included the first direct genomic sequencing method in 1984; initiating the Human Genome Project then as a Research Scientist at newly-formed Biogen Inc. and a Monsanto Life Sciences Research Fellow at UCSF with Gail Martin.

He invented the broadly-applied concepts of molecular multiplexing and tags, homologous recombination methods, and array DNA synthesizers. Technology transfer of automated sequencing & software to Genome Therapeutics Corp. resulted in the first commercial genome sequence (the human pathogen, H. pylori, 1994). He has served in advisory roles for 12 journals (including Nature Molecular Systems Biology), 5 granting agencies and 24 biotech companies (e.g. recently founding Codon Devices and LS9). Current research focuses on integrating biosystems-modeling with the Personal Genome Project & synthetic biology.

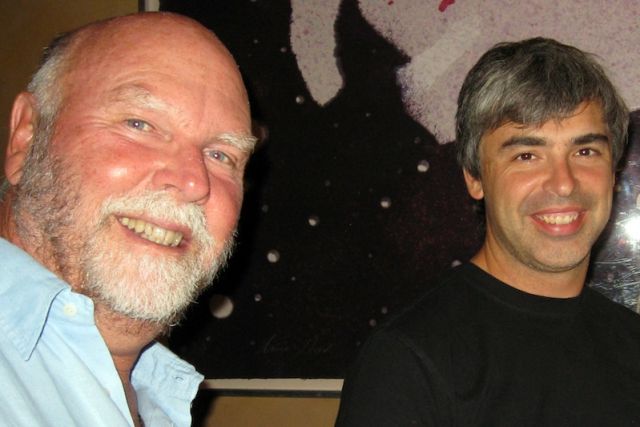

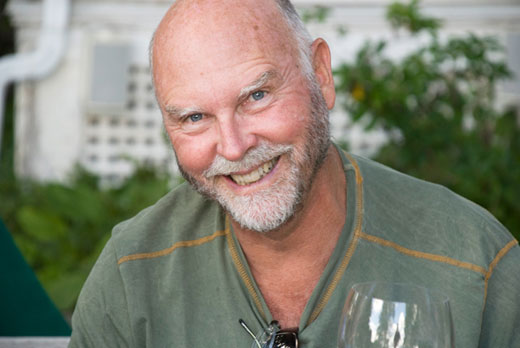

J. CRAIG VENTER is regarded as one of the leading scientists of the 21st century for his invaluable contributions in genomic research, most notably for the first sequencing and analysis of the human genome published in 2001 and the most recent and most complete sequencing of his diploid human in genome in 2007. In addition to his role at SGI, he is founder and chairman of the J. Craig Venter Institute. He was in the news last week with the announcement that SGI had received a $600 million investment from ExxonMobil to develop biofuels from algea.

Venter was the founder of Human Genome Sciences, Diversa Corporation and Celera Genomics. He and his teams have sequenced more than 300 organisms including human, fruit fly, mouse, rat, and dog as well as numerous microorganisms and plants. He is the author of A Life Decoded, as well as more than 200 research articles and is among the most cited scientists in the world. He is the recipient of numerous honorary degrees, scientific awards and a member of many prestigious scientific organizations including the National Academy of Sciences.

INTRODUCTION: APE AND ESSENCE

By George Dyson

Sixty-one years ago Aldous Huxley published his lesser-known masterpiece, Ape and Essence, set in the Los Angeles of 2108. After a nuclear war (in the year 2008) devastates humanity's ability to reproduce high-fidelity copies of itself, a reversion to sub-human existence had been the result. A small group of scientists from New Zealand, spared from the catastrophe, arrives, a century later, to take notes. The story is presented, in keeping with the Hollywood location, in the form of a film script.

On July 24, 2009, a small group of scientists, entrepreneurs, cultural impresarios and journalists that included architects of the some of the leading transformative companies of our time (Microsoft, Google, Facebook, PayPal), arrived at the Andaz Hotel on Sunset Boulevard in West Hollywood, to be offered a glimpse, guided by George Church and Craig Venter, of a future far stranger than Mr. Huxley had been able to imagine in 1948.

In this future — whose underpinnings, as Drs. Church and Venter demonstrated, are here already— life as we know it is transformed not by the error catastrophe of radiation damage to our genetic processes, but by the far greater upheaval caused by discovering how to read genetic sequences directly into computers, where the code can be replicated exactly, manipulated freely, and translated back into living organisms by writing the other way. "We can program these cells as if they were an extension of the computer," George Church announced, and proceeded to explain just how much progress has already been made.

The first day's lectures took place at Elon Musk's SpaceX rocket laboratories — where the latest Merlin and Kestrel engines (built with the loving care devoted to finely-tuned musical instruments) are unchanged, in principle, from those that Theodore von Karman was building at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 1948. The technology of biology, however, has completely changed.

Approaching Beverly Hills along Sunset Boulevard from Santa Monica, the first indications that you are nearing the destination are people encamped at the side of the road announcing "Star Maps" for sale. Beverly Hills is a surprisingly diverse community of interwoven lives, families, and livelihoods, and a Star Map offers only a rough approximation of where a few select people have their homes.

Synthetic Genomics is still at the Star Map stage. But it is becoming Google Earth much faster than most people think.

GEORGE DYSON, a historian among futurists, is the author of Baidarka; Project Orion; and Darwin Among the Machines.

"For those seeking substance over sheen, the occasional videos released at Edge.org hit the mark. The Edge Foundation community is a circle, mainly scientists but also other academics, entrepreneurs, and cultural figures. ... Edge's long-form interview videos are a deep-dive into the daily lives and passions of its subjects, and their passions are presented without primers or apologies. The decidedly noncommercial nature of Edge's offerings, and the egghead imprimatur of the Edge community, lend its videos a refreshing air, making one wonder if broadcast television will ever offer half the off-kilter sparkle of their salon chatter." — Boston Globe

THE CLASS

Stewart Brand, Biologist, Long Now Foundation; Whole Earth Discipline

Larry Brilliant, M.D. Epidemiologist, Skoll Urgent Threats Fund

John Brockman, Publisher & Editor, Edge

Max Brockman, Literary Agent, Brockman, Inc.; What's Next: Dispatches on the Future of Science

Jason Calacanis, Internet Entrepreneur, Mahalo

George Dyson, Science Historian; Darwin Among the Machines

Jesse Dylan, Film-Maker, Form.tv, FreeForm.tv

Arie Emanuel, William Morris Endeavor Entertainment

Sam Harris, Neuroscientist, UCLA; The End of Faith

W. Daniel Hillis, Computer Scientist, Applied Minds; Pattern On The Stone

Thomas Kalil, Deputy Director for Policy for the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and Senior Advisor for Science, Technology and Innovation for the National Economic Council

Salar Kamangar, Vice President, Product Management, Google

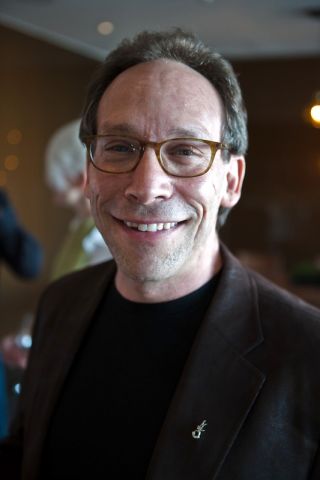

Lawrence Krauss, Physicist, Origins Initiative, ASU; Hiding In The Mirror

John Markoff, Journalist,The New York Times; What The Dormouse Said

Katinka Matson, Cofounder, Edge; Artist, katinkamatson.com

Elon Musk, Physicist, SpaceX; Tesla Motors

Nathan Myhrvold, Physicist, CEO, Intellectual Ventures, LLC, The Road Ahead

Tim O'Reilly, Founder, O'Reilly Media, O'Reilly Radar

Larry Page, CoFounder, Google

Lucy Page Southworth, Biomedical Informatics Researcher, Stanford

Sean Parker, The Founders Fund; CoFounder Napster & Facebook

Ryan Phelan, Founder, DNA Direct

Nick Pritzker, Hyatt Development Corporation

Ed Regis, Writer; What Is Life?

Terrence Sejnowski,Computational Neurobiologist, Salk; The Computational Brain

Maria Spiropulu, Physicist, Cern & Caltech

Victoria Stodden, Computational Legal Scholar, Yale Law School

Richard Thaler, Behavioral Economist, U. Chicago; Nudge

Craig Venter, Genomics Researcher; CEO, Synthetic Genomics; A Life Decoded

Nathan Wolfe, Biologist, Global Virus Forecasting Initiative

Alexandra Zukerman, Assistant Editor, Edge

SESSION 1 @ SPACEX [7.25.09]

Dreams & Nightmares [1:26]

SESSION 2 @ SPACEX [7.25.09]

Constructing Life from Chemicals [1:21]

SESSION 3 @ SPACEX [7.25.09]

Multi-enzyme, multi-drug, and multi-virus resistant life [1:06]

SESSION 4 @SPACEX [7.25.09]

Humans 2.0 [33.15]

SESSION 5 @ ANDAZ [7.26.09]

From Darwin to New Fuels (In A Very Short Time) [34:54]

SESSION 6 @ THE ANDAZ [7.26.09]

Engineering humans, pathogens and extinct species [40:35]

Thanks to Alex Miller and Tyler Crowley of Mahalo.com for shooting, editing, and posting the videos of the Edge Master Class 2009.

EDGE MASTER CLASS 2009 — PHOTO ALBUM

![]()

David Gross, Frank Schirrmacher, Lawrence Krauss, Denis Dutton, Tim O'Reilly, Ed Regis, Victoria Stodden, Jesse Dylan, George Dyson, Alexandra Zukerman

DAVID GROSS

Physicist, Director, Kavki Institute for Theoretical Physics, UCSB; Recipient 2004 Nobel Prize in Physics

"I should have accepted your invitation. I have been listening to the Master Class on the Web — fascinating. I am learning a lot and I wish I had been there. Thanks for the invite and thanks for putting up the videos. ... Invite me again..."

FRANK SCHIRRMACHER

Co-Publisher & Feuilleton Editor, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung

I watched sessions 1 to 6. This is breathtaking. The Edge Master Class must have been spectacular and frightening. Now DNA and computers are reading each other without human intervention, without a human able to understand it. This is a milestone, and adds to the whole picture: we don't read, we will be read. What Edge has achieved collecting these great thinkers around is absolutley spectacular. Whenever I find an allusion to great writers or thinkers, I find out that they all are at Edge.

LAWRENCE KRAUSS

Physicist, Director, Origins Initiative, ASU; Author, Hiding In The Mirror

What struck me was the incredible power that is developing in bioinformatics and genomics, which so resembles the evolution in computer software and hardware over the past 30 years.

George Church's discussion of the acceleration of the Moore's law doubling time for genetic sequencing rates,, for example, was extraordinary, from 1.5 efoldings to close to 10 efoldings per year. When both George and Craig independently described their versions of the structure of the minimal genome appropriate for biological functioning and reproduction, I came away with the certainty that artificial lifeforms will be created within the next few years, and that they offered great hope for biologically induced solutions to physical problems, like potentially buildup of greenhouse gases.

At the same time, I came away feeling that the biological threats that come with this emerging knowledge and power are far greater than I had previously imagined, and this issue should be seriously addressed, to the extent it is possible. But ultimately I also came away with a more sober realization of the incredible complexity of the systems being manipulated, and how far we are from actually developing any sort of comprehensive understanding of the fundamental molecular basis of complex life. The simple animation demonstrated at the molecular level for Gene expression and replication demonstrated that the knowledge necessary to fully understand and reproduce biochemical activity in cells is daunting.

Two other comments: (1) was intrigued by the fact that the human genome has not been fully sequenced, in spite of the hype, and (2) was amazed at the available phase space for new discovery, especially in forms of microbial life on this planet, as demonstrated by Craig in his voyage around the world, skimming the surface, literally, of the ocean, and of course elsewhere in the universe, as alluded to by George.

Finally, I also began to think that structures on larger than molecular levels may be the key ones to understand for such things as memory, which make the possibilities for copying biological systems seem less like science fiction to me. George Church and I had an interesting discussion about this which piqued my interest, and I intend to follow this up.

DENIS DUTTON

Philosopher; Founder & Editor, Arts & Letters Daily; Author, The Art Instinct

Astonishing.

TIM O'REILLY

Founder, O'Reilly Media, O'Reilly Radar

George Church asked "Is life a qualitative or quantitative question?" Every revolution in science has come when we learn to measure and count rather than asking binary qualitative questions. Church didn't mention phlogiston, but it's what came to mind as a good analogy. Heat is not the presence or absence of some substance or quality, but rather a measurable characteristic of a complex thermodynamic system. Might not the same be true of life?

The measurement of self-replication as a continuum opens quantitative vistas. Here are a few tidbits from George Church and Craig Venter:

• The most minimal self-replicating system measured so far has 151 genes; bacteria and yeast about 4000; humans about 20,000.

• There are 12 possible amino acid bases (6 pairs); we ended up using 4 bases (2 pairs); other biological systems are possible.

• Humans are actually an ecology, not just an organism. The human microbiome: 23K human genes, 10K bacterial genes.

• Early estimates of the number of living organisms were limited to those that could be cultured in the laboratory; by sampling the DNA in water and soil, we have discovered that we undercounted by many orders of magnitude

• The biomass of bacteria deep in the earth is greater than the biomass of all visible plants and animals; ditto the biomass of ocean bacteria.

• The declining cost of gene sequencing is outpacing Moore's Law (1.5x/year): the number of base pairs sequenced per dollar is increasing at 10x per year.

Net: The current revolution in genomics and synthetic biology will be as profound as the emergence of modern chemistry and physics from medieval alchemy.

ED REGIS

Writer; What Is Life?

Almost fifteen years ago, in a profile of Leroy Hood, I quoted Bill Gates, who said: "The gene is by far the most sophisticated program around."

At the Edge Master Class last weekend I learned the extent to which we are now able to reprogram, rework, and essentially reinvent the gene. This gives us a degree of control over biological organisms — as well as synthetic ones — that was considered semi-science fictional in 1995. Back then scientists had genetically engineered E. coli bacteria to produce insulin. At the Edge event, by contrast, Craig Venter was talking about bacteria that could convert coal into methane gas and others that could produce jet fuel. It was merely a matter of doing the appropriate genomic engineering: by replacing the genome of one organism with that of another you could transform the old organism into something new and better.

George Church, for his part, described the prospect of synthetic organisms grown from mirror-image DNA; humanized mice, injected with human genes so that they would produce antibodies that the human body would not reject; and the possibility of resurrecting extinct species including the woolly mammoth and Neanderthal man.

But as far-out as these developments were, none of them was really surprising. After all, science and technology operate by systematically gaining knowledge of the world and then applying it intelligently. Thus we skip from miracle to miracle.

More extraordinary to me personally was the fact that the first day of the EDGE event was being held on the premises of a private rocket manufacturing facility in Los Angeles, SpaceX, which also builds Tesla electric vehicles, all under the leadership of Internet entrepreneur Elon Musk. The place was mildly unbelievable, even after having seen it with my own eyes. In the age of Big Science, where it is not uncommon for scientific papers to be written by forty or more coauthors, the reign of the individual is not yet dead.

VICTORIA STODDEN

Computational Legal Scholar, Yale Law School

Craig Venter posed the question whether it is possible to reconstruct life from its constituent parts. Although he's come close, he hasn't done it (yet?) and neither has anyone else. Aside from the intrinsic interest of the question, its pursuit seems to be changing biological research in two fundamental ways encapsulated Venter's own words:

We have these 20 millions genes. I view these as design components. We actually have software now for designing species, where we can try and put these components together. The biggest problem with engineering biology on first principles is that we don't know too many first principles. It's a minor problem! In fact, from doing this, if we build this robot that can make a million chromosomes a day, and a million transformations, and a million new species versions, it'll be the fastest way to establish what the first principles are, if we can track all that information and all the changes.

Unlike physics or more mathematical fields, research in biology traditionally hasn't been a search for underlying principles, or had the explicit goal of developing grand unifying theories. A cynic could even argue funding incentives in biology encourage complexity: big labs are funded if they address very complicated, and thus more expensive to research, phenomena. Whether or not that's true, chemical reconstruction of the genome is a process from first principles, marking a change in approach that brings biological research closer in spirit to more technical fields. Venter seems to believe that answering questions such as, "Can we reconstruct life from its components?" "What genes are necessary for life?" "What do you really need to run cellular machinery?" and "What is a minimal organism that could survive?" will uncover first principles in biology, potentially structuring understanding deductively.

Venter's use of combinatorial biological research is another potential sea-change in the way understanding is developed. This use of massive computing is analogous to that occurring in many other areas of scientific research, and the key is that discovery becomes less constrained by a priori assumptions or models (or understanding?).

Moore's Law and ever cheaper digital storage is giving scientists the luxury of solution search within increasingly large problem spaces. With complete search over the space of all possible solutions, in principle it is no longer necessary to reason one's way to the (an?) answer. This approach favors empirical evaluation over deductive reasoning. In Venter's biological context, presumably if automated search can find viable new species it will then be possible to investigate their unique life enabling characteristics. Perhaps through automated search?

JESSE DYLAN

Film-Maker, Form.tv, FreeForm.tv

What a revelation the The Master Class in Synthetic Genomics was. In addition to being informative on so many literal levels it reinforced the mystery and wonder of the world. George Church and Craig Venter were generous to give us a glimpse of where we are today and fire the imagination of where we are going. It's all science but seems beyond science fiction — living forever, reprogramming genes, resurrecting extinct species. All told at SpaceX — a place where people are reaching for the stars, not just thinking about it but building rockets to take us there. Where Elon Musk contemplates the vastness of space and our tiny place in it, where we gained a perspective on the things that are very small and beyond the vision of our eyes. So small it's a wonder we even know they are there. Thanks for giving us a profound glimpse into the future.

We are in such an early formative stage it makes one wonder where we will be in a hundred or even a thousand years. It's nice to be up against mysteries.

GEORGE DYSON

Science Historian; Darwin Among the Machines

End Of Species

We speak of reading and writing genomes — but no human mind can comprehend these lengthy texts. We are limited to snippet view in the library of life.

As Edge's own John Markoff reported from the recent Asilomar conference on artificial intelligence, the experts "generally discounted the possibility of highly centralized superintelligences and the idea that intelligence might spring spontaneously from the Internet."

Who will ever write the code that ignites the spark? Craig Venter might be hinting at the answer when he tells us that "DNA... is absolutely the software of life." The language used by DNA is much closer to machine language than any language used by human brains. It should be no surprise that the recent explosion of coded communication between our genomes and our computers largely leaves us out.

"The notion that no intelligence is involved in biological evolution may prove to be one of the most spectacular examples of the kind of misunderstandings which may arise before two alien forms of intelligence become aware of one another," wrote viral geneticist (and synthetic biologist) Nils Barricelli in 1963. The entire evolutionary process "is a powerful intelligence mechanism (or genetic brain) that, in many ways, can be comparable or superior to the human brain as far as the ability of solving problems is concerned," he added in 1987, in the final paper he published before he died. "Whether there are ways to communicate with genetic brains of different symbioorganisms, for example by using their own genetic language, is a question only the future can answer."

We are getting close.

ALEXANDRA ZUKERMAN

Assistant Editor, Edge

As the meaning of George Church and Craig Venter's words permeated my ever-forming pre-frontal cortex at the Master Class, I cannot deny that I felt similarly to the way George Eliot described her own emotions in 1879. Eliot, speaking as Theophrastus in a little-known collection of essays published that year, predicts that evermore perfecting machines will imminently supercede the human race in "Shadows of the Coming Race":

When, in the Bank of England, I see a wondrously delicate machine for testing sovereigns, a shrewd implacable little steel Rhadamanthus that, once the coins are delivered up to it, lifts and balances each in turn for the fraction of an instant, finds it wanting or sufficient, and dismisses it to right or left with rigorous justice; when I am told of micrometers and thermopiles and tasimeters which deal physically with the invisible, the impalpable, and the unimaginable; of cunning wires and wheels and pointing needles which will register your and my quickness so as to exclude flattering opinion; of a machine for drawing the right conclusion, which will doubtless by-and-by be improved into an automaton for finding true premises — my mind seeming too small for these things, I get a little out of it, like an unfortunate savage too suddenly brought face to face with civilisation, and I exclaim —

'Am I already in the shadow of the Coming Race? and will the creatures who are to transcend and finally supersede us be steely organisms, giving out the effluvia of the laboratory, and performing with infallible exactness more than everything that we have performed with a slovenly approximativeness and self-defeating inaccuracy?'1

Whereas Theophrastus' friend, Trost (a play on Trust) is confident that the human being is and will remain the "nervous center to the utmost development of mechanical processes" and that "the subtly refined powers of machines will react in producing more subtly refined thinking processes which will occupy the minds set free from grosser labour," Theophrastus feels "average" and less energetic, readily imagining his subjugation by these steely organisms giving out the "effluvia of the laboratory." He imagines instead that machines operate upon him, measuring his thoughts and quickness of mind. Micrometers, thermopiles and tasimeters were invading the sanctity of his consciousness with their "unconscious perfection." As George Church told us that "We're getting to a point where we can really program these cells as if they were an extension of a computer" and "This software builds its own hardware — it turns out biology does this really well," my sensibilities felt slightly jarred. Indeed, I felt as though I might be from an uncivilized time and place, suddenly finding myself on the platform as a flying train whizzed past (in fact, our tour of SpaceX and Tesla by Elon Musk was not far off!).

I asked myself the same question as George Eliot posed to herself over one hundred years ago: If computing and genetics are converging, such that computers will be reading our genomes and perfecting them, has not Eliot's prediction come true? I wondered, as a historian of science, not as much about the implications of such a development, but more about why computers have become so powerful. Why do we trust, as Trost does, artificial intelligence so much? Will scientists ultimately give their agency over to computers as we get closer to mediating our genomes and that of other forms of life? Will computers and artificial intelligence become a new "invisible hand" such as that which guides the free market without human intervention? I am curious about the role computers will be playing, as humans grant them more and more hegemony.

___1George Eliot, Impressions of Theophrastus Such

LAWRENCE KRAUSS

Physicist, Director, Origins Initiative, ASU; Author, Hiding In The Mirror

What struck me was the incredible power that is developing in bioinformatics and genomics, which so resembles the evolution in computer software and hardware over the past 30 years.

George Church's discussion of the acceleration of the Moore's law doubling time for genetic sequencing rates,, for example, was extraordinary, from 1.5 efoldings to close to 10 efoldings per year. When both George and Craig independently described their versions of the structure of the minimal genome appropriate for biological functioning and reproduction, I came away with the certainty that artificial lifeforms will be created within the next few years, and that they offered great hope for biologically induced solutions to physical problems, like potentially buildup of greenhouse gases.

At the same time, I came away feeling that the biological threats that come with this emerging knowledge and power are far greater than I had previously imagined, and this issue should be seriously addressed, to the extent it is possible. But ultimately I also came away with a more sober realization of the incredible complexity of the systems being manipulated, and how far we are from actually developing any sort of comprehensive understanding of the fundamental molecular basis of complex life. The simple animation demonstrated at the molecular level for Gene expression and replication demonstrated that the knowledge necessary to fully understand and reproduce biochemical activity in cells is daunting.

Two other comments: (1) was intrigued by the fact that the human genome has not been fully sequenced, in spite of the hype, and (2) was amazed at the available phase space for new discovery, especially in forms of microbial life on this planet, as demonstrated by Craig in his voyage around the world, skimming the surface, literally, of the ocean, and of course elsewhere in the universe, as alluded to by George.

Finally, I also began to think that structures on larger than molecular levels may be the key ones to understand for such things as memory, which make the possibilities for copying biological systems seem less like science fiction to me. George Church and I had an interesting discussion about this which piqued my interest, and I intend to follow this up.

FRANKFURTER ALLGEMEINE ZEITUNG

15. August 2009 FEUILLETON

GENETIC ENGINEERING

THE CURRENT CATALOG OF LIFE [Der Aktuelle Katalog Der Schöpfung Ist Da] By Ed Regis

[ED. NOTE: Among the attendees of the recent Edge Master Class 2009 — A Short Course on Synthetic Genomics, was science writer Ed Regis (What Is Life?) who was commissioned by Frank Schirrmacher, Co-Publisher and Feuilleton Editor of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung to write a report covering the event. A German translation of Regis's article was published on August 15th by FAZ along with an accompanying article. The original English language version is published below with permission.]

In their futuristic workshops, the masters of the Synthetic Genomics, Craig Venter and George Church, play out their visions of bacteria reprogrammed to turn coal into methane gas and other microbes programmed to create jet fuel

14. August 2009 — John Brockman is a New York City literary agent with a twist: not only does he represent many of the world's top scientists and science writers, he's also founder and head of the Edge Foundation (www.edge.org), devoted to disseminating news of the latest advances in cutting-edge science and technology. Over the weekend of 24-26 July, in Los Angeles, Brockman's foundation sponsored a "master class" in which two of these same scientists — George Church, a molecular geneticist at Harvard Medical School, and Craig Venter, who helped sequence the human genome — gave a set of lectures on the subject of synthetic genomics. The event, which was by invitation only, was attended by about twenty members of America's technological elite, including Larry Page, co-founder of Google; Nathan Myhrvold, formerly chief technology officer at Microsoft; and Elon Musk, founder of PayPal and head of SpaceX, a private rocket manufacturing and space exploration firm which is housed in a massive hangar-like structure near Los Angeles International Airport. The first day's session, in fact, was held on the premises of SpaceX, where the Tesla electric car is also built.

Synthetic genomics, the subject of the conference, is the process of replacing all or part of an organism's natural DNA with synthetic DNA designed by humans. It is essentially genetic engineering on a mass scale. As the participants were to learn over the next two days, synthetic genomics will make possible a variety of miracles, such as bacteria reprogrammed to turn coal into methane gas and other microbes programmed to churn out jet fuel. Still other genomic engineering techniques will allow scientists to resurrect a range of extinct creatures including the woolly mammoth and, just maybe, even Neanderthal man.

The specter of "biohackers" creating new infectious agents made its obligatory appearance, but synthetic genomic researchers are, almost of necessity, optimists. George Church, one of whose special topics was "Engineering Humans 2.0," told the group that "DNA is excellent programmable matter." Just as automated sequencing machines can read the natural order of a DNA molecule, automated DNA synthesizing machines can create stretches of deliberately engineered DNA that can then be placed inside a cell so as to modify its normal behavior. Many bacterial cells, for example, are naturally attracted to cancerous tumors. And so by means of correctly altering their genomes it is possible to make a species of cancer-killing bacteria, organisms that attack the tumor by invading its cancerous cells, and then, while still inside them, synthesizing and then releasing cancer-killing toxins. ??Church and his Harvard lab team have already programmed bacteria to perform each of these functions separately, but they have not yet connected them all together into a complete and organized system. Still, "we're getting to the point where we can program these cells almost as if they were computers," he said.

But tumor-killing microbes were only a small portion of the myriad wonders described by Church. Another was the prospect of "humanized" or — even "personalized" — mice. These are mammals whose genomes are injected with bits of human DNA for the purpose of getting the animals to produce disease-fighting antibodies that would not be rejected by humans. A personalized mouse, whose genome was modified with some of your very own genetic material, would produce antibodies that would not be rejected by your own body.

Beyond that is the possibility of creating synthetic organisms that would be resistant to a whole class of natural viruses. There are two ways of doing this, one of which involves creating DNA that is a mirror-image of natural DNA. Like many biological and chemical substances, DNA has a chirality or handedness, the property of existing in either left-handed or right-handed structural forms. In their natural state, most biological molecules including DNA and viruses are left-handed. But by artificially constructing right-handed DNA, it would be possible to make synthetic living organisms whose DNA is a mirror-image of the original. They would be resistant to conventional enzymes, parasites, and predators because their DNA would not be recognized by the mirror-image version. Such synthetic organisms would constitute a whole new "mirror-world" of living things.

Church is also founder and head of the Personal Genome Project, or PGP. The project's purpose, he said, is to sequence the genomes of 100,000 volunteers with the goal of opening up a new era of personalized medicine. Instead of today's standardized, one-size-fits-all collection of pills and therapies, the medicine of the future will be genomically tailored to each individual patient, and its treatments will fit him or her as well as a made-to-order suit of clothes. Church also speculated that knowledge of the idiosyncratic features that lurk deep within each of our genomes — genetic differences that give rise to every person's respective set of individuating traits — will bring us an unprecedented level of self-understanding, and, therefore, will allow us to chart a more intelligent and informed course through life.

Toward the end of the first day Elon Musk, for whom the word charismatic could have well been coined, described a genomic transformation of another type. While a video of his Falcon 1 rocket being launched from the Kwajalein Atoll in the South Pacific played in the background, Musk spoke about sending the human species to the planets. That might have seemed an unrealistic goal were it not for the fact that on 13 July, just twelve days prior to the Edge event, SpaceX had successfully launched another Falcon 1 rocket that had placed Malaysia's RazakSAT into Earth orbit. Earlier, competing against both Boeing and Lockheed, SpaceX had won NASA's Commercial Orbital Transportation Services competition to resupply cargo to the International Space Station.

Then, like an emperor leading his subjects, Musk gave the conference attendees a tour of his spacecraft manufacturing facility. We saw the rocket engine assembly area, several launch vehicle components under construction, the mission operations area, and an example of the company's Dragon spacecraft, a pressurized capsule for the transport of cargo or passengers to the ISS.

"This is all geared to extending life beyond earth to a multiplanet civilization," Musk said of the spacecraft. Suddenly, his particular version of the future was no longer so unbelievable.

The leadoff speaker on the second and last day of the conference was J. Craig Venter, the human genome pioneer who more recently cofounded Synthetic Genomics Inc., an organization devoted to commercializing genomic engineering technologies. One of the challenges of synthetic genomics was to pare down organisms to the minimal set of genes needed to support life. Venter called this "reductionist biology," and said that a fundamental question was whether it would be possible to reconstruct life by putting together a collection of its smallest components.

Brewer's yeast, Venter discovered, could assemble fragments of DNA into functional chromosomes. He described a set of experiments in which he and colleagues created 25 small synthetic pieces of DNA, injected them into a yeast cell, which then proceeded to assemble the pieces into a chromosome. The trick was to design the DNA segments in such a way that the organism puts them together in the correct order. It was easy to manipulate genes in yeast, Venter found. He could insert genes, remove genes, and create a new species with new characteristics. In August 2007, he actually changed one species into another. He took a chromosome from one cell and put it into different one. "Changing the software [the DNA] completely eliminated the old organism and created a new one," Venter said.

Separately, Venter and his group had also created a synthetic DNA copy of the phiX virus, a small microbe that was not infectious to humans. When they put the synthetic DNA into an E. coli bacterium, the cell made the necessary proteins and assembled them into the actual virus, which in turn killed the cell that made it. All of this happened automatically in the cell, Venter said: "The software builds its own hardware."

These and other genomic creations, transformations, and destructions gave rise to questions about safety, the canonical nightmare being genomically engineered bacteria escaping from the lab and wreaking havoc upon human, animal, and plant. But a possible defense against this, Venter said, was to provide the organism with "suicide genes," meaning that you create within them a chemical dependency so that they cannot survive outside the lab. Equipped with such a dependency, synthetic organisms would pose no threat to natural organisms or to the biosphere. Outside the lab they would simply die.

That would be good news if it were true, because with funding provided by ExxonMobil, Venter and his team are now building a three to five square-mile algae farm in which reprogrammed algae will produce biofuels.

"Making algae make oil is not hard," Venter said. "It's the scalability that's the problem." Algae farms of the size required for organisms to become efficient and realistic sources of energy are expensive. Still, algae has the advantage that it uses CO2 as a carbon source — it actually consumes and metabolizes a greenhouse gas — and uses sunlight as an energy source. So what we have here, potentially, are living solar cells that eat carbon dioxide as they produce new hydrocarbons for fuel.

George Church had the final say in a lecture entitled "Engineering Humans 2.0." Human beings, he noted, are limited by a variety of things: by their ability to concentrate and remember, by the shortness of their lifespans, and so on. Genomic engineering could be used to correct all these deficiencies and more. The common laboratory mouse, he noted, had an average lifespan of 2.5 years. The naked mole rate, by contrast, lives ten times longer, to the ripe old age of 25. It would be possible to find the genes that contributed to the longevity of the naked mole rat, and by importing those genes into the lab mouse, you could slowly increase its longevity.

An analogous process could also be tried on human beings, increasing their lifespans and adding to their memory capacity, but the question was whether it was wise to do this. There were always trade-offs, Church said. You may engineer humans to have bigger and stronger bones, but only at the price if making them heavier and more ungainly. Malaria resistance is coupled with increased susceptibility to sickle cell anemia. And so on down the list. In a conference characterized by an excess of excess, Church provided a welcome cautionary note.

But then he proceeded to pull out all the stops an argued that by targeted genetic manipulation of the elephant genome it might be possible to resurrect the woolly mammoth. And by doing the same to the chimpanzee genome, scientists could possibly resurrect Neanderthal man.

"Why would anyone want to resurrect Neanderthal man?" a conference participant asked.

"To create a sibling species that would give us a fresh outlook on ourselves," Church answered. Humans were a monoculture, he said, and monocultures were biologically at risk.

His answer did not satisfy all of those present. "We already have enough Neanderthals in Washington," Craig Venter quipped, thereby effectively bringing the Edge Master Class 2009 to a close. ?

Ed Regis is the author of several science books, most recently, What Is Life? Investigating the Nature of Life in the Age of Synthetic Biology

SUEDDEUTSCHE ZEITUNG

August 13 , 2009

FEUILLETON

THE WALKMAN OF GENETIC ENGINEERING: THE MOVE FROM SCIENCE TO A NEW WORLD OF PRODUCTS

[Walkman der Gentechnik; Der Schritt von der Wissenschaft zu einer neuen Warenwelt] By Andrian Kreye, Editor, The Feuilleton, Sueddeutsche Zeitung

...Genetic engineering is now at a point where computer science was around the mid-eighties. The early PCs were limited as to purpose and network. In two and a half decades, the computer has led us into a digial world in which every aspect of lives has been affected. According to Moore's Law, the performance of computers doubles every 18 months. Genetic engineering is following a similar growth. On the last weekend in July, Craig Venter and George Church met in Los Angeles to lead a seminar on synthetic genetic engineering for John Brockman's science forum Edge.org.

Genetic engineering under Church has been following the grwoth of computer science growing by a factor of tenfold per year. After all, the cost of sequencing a genome dropped from three billion dollars in 2000 to around $50 000 dollars as Stanford University's Dr. Steven Quake genomics engineer announced this week. 17 commercial companies already offer similar services. In June, a "Consumer Genetics" exhibition was held in Boston for the first time. The Vice President of Knome, Ari Kiirikki, assumes that the cost of sequencing a genome in the next ten years will fall to less than $1,000. In support for this development, the X-Prize Foundation has put up a prize of ten million dollars for the sequencing of 100 full genomes within ten days for the cost of less than $10,000 dollars per genome sequenced. ??It is now up to the companies themselves to provide an ethical and legal standing to commercial genetic engineering. The States of New York and California have already made the sale of genetic tests subject to a prescription. This is however only a first step is to adjust a new a new commercialized science which is about to cause enormous changes similar to those brought about be computer science. Medical benefits are likely to be enormous. Who knows about dangers in its genetic make-up, can preventive measures meet. The potential for abuse is however likewise given. Health insurances and employers could discriminate against with the DNS information humans. Above all however our self-understanding will change. Which could change, if synthetic genetic engineering becomes a mass market, is not yet foreseeable. For example, Craig Venter is working on synthetic biofuels. If successful, such a development would re-align technology, economics and politics in a fundamental way. Of one thing we can already be certain. The question of whether genetic engineering will becomes available for all is no longer on the table. It has already happened.

SPIEGEL ONLINE

13.08. 2009

FEUILLETON-PRESSESCHAU

Süddeutsche Zeitung, 13.08.2009

Von aktuellen Entwicklungen aus der schönen neuen Welt der Genom-Sequenzierung berichtet Andrian Kreye: "Am letzten Juliwochenende trafen sich Craig Venter und George Church in Los Angeles, um für John Brockmans Wissenschaftsforum Edge.org ein Seminar über synthetische Gentechnik zu leiten. Die Gentechnik, so Church, habe die Informatik dabei längst hinter sich gelassen und entwickle sich mit einem Faktor von zehn pro Jahr. Immerhin - der Preis für die Sequenzierung eines Genoms ist von drei Milliarden Dollar im Jahr 2000 auf rund 50.000 Dollar gefallen, wie der Ingenieur der Stanford University Dr. Steven Quake diese Woche bekanntgab. 17 kommerzielle Firmen bieten ihre Dienste schon an."