EDGE CONVERSATIONS

HOW TO BE A SYSTEMS THINKER

A Conversation with Mary Catherine Bateson [4.17.18]

At the moment, I’m asking myself how people think about complex wholes like the ecology of the planet, or the climate, or large populations of human beings that have evolved for many years in separate locations and are now re-integrating. To think about these things, I find that you need something like systems theory. So, I went back to thinking about systems theory two or three years ago, which I hadn’t for quite a long time.

What prompted it was concern about the state of the world. One of the things that we’re all seeing is that a lot of work that has been done to enable international cooperation in dealing with various problems since World War II is being pulled apart. We’re seeing the progress we thought had been made in this country in race relations being reversed. We’re seeing the partial breakup—we don’t know how far that will go—of a united Europe. We’re moving ourselves back several centuries in terms of thinking about what it is to be human, what it is to share the same planet, how we’re going to interact and communicate with each other. We’re going to be starting from scratch pretty soon.

Until fairly recently, artificial intelligence didn’t learn. To create a machine that learns to think more efficiently was a big challenge. In the same sense, one of the things that I wonder about is how we'll be able to teach a machine to know what it doesn’t know that it might need to know in order to address a particular issue productively and insightfully. This is a huge problem for human beings. It takes a while for us to learn to solve problems, and then it takes even longer for us to realize what we don’t know that we would need to know to solve a particular problem.

The tragedy of the cybernetic revolution, which had two phases, the computer science side and the systems theory side, has been the neglect of the systems theory side of it. We chose marketable gadgets in preference to a deeper understanding of the world we live in. [Continue ]

CROSSING CULTURES

A Conversation with Mary Catherine Bateson [10.11.00]

After I got my doctorate, when I was teaching Arabic at Harvard, I volunteered to teach a section of Erik Erikson's course on The Human Life Cycle, which planted a seed of interest in the way people live their lives. I picked that up when I wrote the memoir of my parents and then I went into writing Composing a Life where I looked at a number of women's lives. So although I had not taught on life histories since the Erikson experience, when I went to Mason I began teaching courses related to life histories, autobiography, the life cycle, in various different forms, sometimes about men and women, sometimes just women, sometimes memoirs of adolescence. I've also taught a course with the title "Ecology and Culture." And in some years I've taught a course about the relationship between medical risk on the one hand and race and gender on the other.

Ecology and Culture is most commonly taught in terms of the way a given environment determines the possible cultural patterns that human societies develop to adapt to that environment, sometimes also in terms of the impact of a given human community. What I was mainly focusing on, however, came out of work that I'd done with my father, namely the relationship between the ideas, the beliefs, the understandings, and so on, of a group of people and the way they impact their environment. Gregory believed that the way we in industrial civilization mistreat the natural world comes from a set of cultural premises, starting with the body-mind separation—deeply embedded cultural premises that are built into the experience of growing up, are deep in our theoretically secular educational system and played out in the economy and so on. Such premises are often expressed in religious terms, but of course such socially constructed concepts as "money" or "credit" are our equivalent of deities or ancestral ghosts, telling us how to run our lives.

I was very interested in the work of an anthropologist named Roy Rappoport, who wrote about the way the ritual cycle of a New Guinea people regulated both their impact on their environment and their rhythms of warfare and peace-making. Basically what I did in "Ecology and Culture" was to pose the question of how ideas, particularly religious ideas, but not exclusively so, and the way they're expressed, may regulate or moderate the impact of a group on their natural environment. [ Continue ]

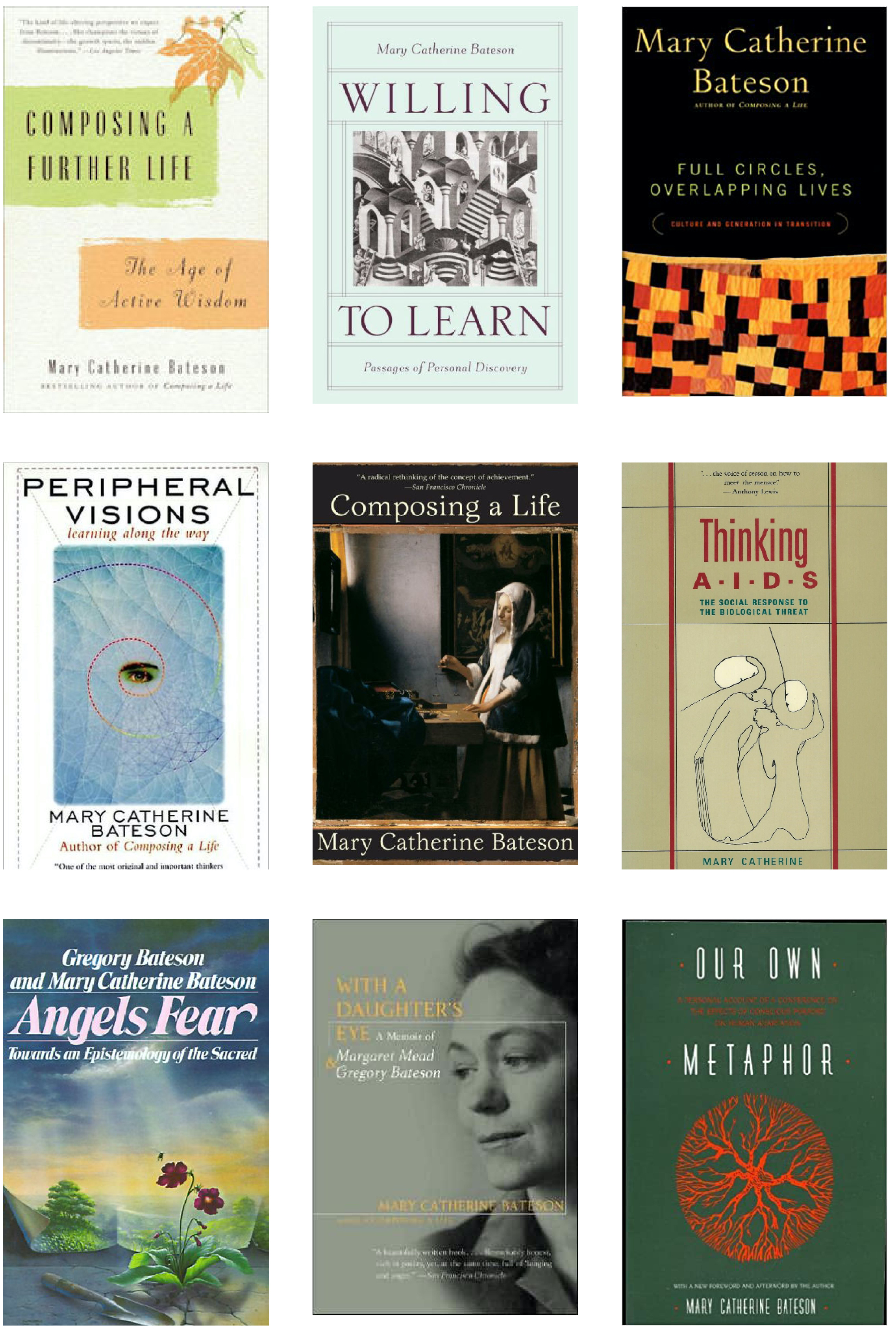

BOOKS BY MARY CATHERINE BATESON

Composing a Further Life: The Age of Active Wisdom (2010)

Willing to Learn: Passages of Personal Discovery (2004)

Full Circles, Overlapping Lives: Culture and Generation in Transition (2000)

Peripheral Visions: Learning Along the Way (1994)

Composing a Life (1989)

Thinking AIDS (1988) with Richard Goldsby

Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred (1987) with Gregory Bateson

With a Daughter's Eye: A Memoir of Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson (1984)

Our Own Metaphor: A Personal Account of a Conference on the Effects of Conscious Purpose on Human Adaptation (1972)

BOOK CHAPTERS

CURIOUS MINDS: HOW A CHILD BECOMES A SCIENTIST

Patterns and the Participant Observer

by Mary Catherine Bateson

Neither of my parents—the anthropologists Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead—made much division between their professional and personal lives. Theories and observations filled the conversations I listened to at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. When my father was away, and after my parents separated, the same pattern continued with whatever colleagues and friends came visiting. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

When I was growing up, it was supposed to be fairly clear that boys modeled themselves on their fathers and girls modeled themselves on their mothers, but following the same-sex pattern often involved competition and rebellion, especially for boys, and limited the options available to girls. I had the still unusual experience of growing up in an egalitarian household, in which my two parents were strikingly different and both available as models, with no gender rules determining the choice. [ Continue ]

Excerpted from Curious Minds: How a Child Becomes a Scientist by John Brockman, Vintage Books, 2004

HOW THINGS ARE: A SCIENCE TOOL-KIT FOR THE MIND

On the Naturalness of Things

by Mary Catherine Bateson

Clear thinking about the world we live in is hindered by some very basic muddles, new and old, in the ordinary uses of the words nature and natural.

The effect of this was to create two different kinds of causality and separate spheres of discourse that must someday be brought back together. The folk distinctions that describe the concept of "nature" are messier but equally insidious. As with Cartesian dualism, they tend to slant ethical thinking, to create separation rather than inclusion. In Western culture, nature was once something to be ruled by humankind, as the body was to be ruled by the mind.

Recently, we have complicated the situation by labelling more and more objects and materials preferentially, from foodstuff to fibbers to molecules, as natural or unnatural. This sets up a limited and misshapen domain for the natural: loaded with unstated value judgments: the domain suggested in Bill McKibben's title The End Of Nature or in William Irwin Thompson's The American Replacement of Nature: Yet nature is not something that can end or be replaced, anymore than it is possible to get outside of it.

In fact, everything is natural; if it weren't, it wouldn't be. That's How Things Are: natural. And interrelated in ways that can (sometimes) be studied to produce those big generalizations we call "laws of nature" and the thousands of small interlocking generalizations that make up science. Somewhere in this confusion there are matters of the greatest importance, matters that need to be clarified so that it is possible to argue (in ways that are not internally contradictory) for the preservation of "nature," for respect for the "natural world," for education in the "natural sciences," and for better scientific understanding of the origins and effects of human actions. But note that the nature in "laws of nature" is not the same as the nature in "natural law," which refers to a system of theological and philosophical inquiry that tends to label the common sense of Western Christendom as "natural."

Ours is a species among others, part of nature, with recognizable relatives and predecessors, shaped by natural selection to a distinctive pattern of adaptation that depends on the survival advantages of flexibility and extensive learning. Over millennia, our ancestors developed the opposable thumbs that support our cleverness with tools, but rudimentary tools have been observed in other primates; neither tools nor the effects of tools are "unnatural." Human beings communicate with each other, passing on the results of their explorations more elaborately than any other species. Theorists sometimes argue that human language is qualitatively or absolutely different from the systems of communication of other species; but this does not make language (or even the possibilities of error and falsehood that language amplifies) "unnatural." Language is made possible by the physical structures of the human nervous system, which also allow us to construct mental images of the world. So do the perceptual systems of bats and frogs and rattlesnakes, each somewhat different, to fit different adaptive needs. [ Continue ]

Excerpted from How Things Are: A Science Tool-Kit for the Mind by John Brockman & Katinka Matson, Harper Perennial, 2004

Bateson Responds to The Edge Question (1998-2018)

"What Is the Last Question?" (2018)

Will the process of discovery be completed in any of the natural sciences?

"What Do You Consider the Most Interesting Recent [Scientific] News? What Makes It Important?" (2016)

News That Stayed News

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first artificial satellite to this planet. That was very big news, the beginning of an era of space exploration involving multiple launchings and satellites spending long periods in orbit, launched from many nations. In the weeks after Sputnik, however, another news story played out that led to a range of other actions based on the recognition that US education was falling behind, not only in science but in other fields of education as well, such as geography and foreign languages. This is still true. We are not behind at the cutting edge, but we are behind in a general, broad-based understanding of science, and this is not tolerable for a democracy in an increasingly technological world.

The most significant example is climate change. It turns out, for instance, that many basic terms are unintelligible to newspaper readers. Recently, I encountered the statement that "a theory is just a guess—and that includes evolution"—not to mention most of what has been reconstructed by cosmologists about the formation of the universe. When new data is published that involves a correction or expansion of earlier work, this is taken to indicate weakness, rather than the great strength of scientific work as an open system, always subject to correction by new information. When the winter temperature dips below freezing, you hear, "This proves that the earth is not warming." Most Americans are not clear on the difference between "weather" and "climate." The United States government supports the world’s most advanced research on climate, but the funds to do so are held hostage by politicians convinced that it is a hoax. And we can add trickle-down economics and theories of racial and gender inferiority to the list of popular prejudices that many Americans believe are ratified by science, not to mention the common conclusion that the "War on Poverty failed." Why do we believe that violence is a solution? [ Continue ]

It is a great boon when computers perform operations that we fully understand faster and more accurately than humans are able to do, but not a boon when we use them in situations that are not fully understood. We cannot expect them to make aesthetic judgments, to show compassion or imagination, for these are capacities that remain mysterious in human beings.

Machines that think are likely to be used to make decisions on the basis of the operations they are ostensibly able to perform. For instance, we now frequently see letters, manuscripts, or (most commonly) student papers in which corrections proposed by spell-check have been allowed to stand without review: the writer meant "mod," but the program decided he meant "mad." How tempting to leave the decision to the machine. I referred in an email to a plan to meet with someone in Santa Fe on my way to an event in Texas, using the word "rendezvous," and the computer married me off by announcing that the trip was to "render vows." Can a computer be programmed to support "family values"? Any values at all? We now have drones that, aimed in a given direction, are able to choose their targets on arrival, with an unfortunate tendency to attack wedding parties as conviviality comes to appear sinister. We can surely program machines to prescribe drugs and medical procedures, but it seems unlikely that machines will do better than people in following the injunction to do no harm. [ Continue ]

The Illusion of Certainty

Scientists sometimes resist new ideas and hang on to old ones longer than they should, but the real problem is the failure of the public to understand that the possibility of correction or disproof is a strength and not a weakness. We live in an era when it is increasingly important that the voting public be able to evaluate scientific claims and be able to make analogies between different kinds of phenomena, but this can be a major source of error. The process by which scientific knowledge is refined is largely invisible to the public. The truth-value of scientific knowledge is dependent upon its openness to correction, yet we all carry around ideas that science has long since revised—and are disconcerted when asked to abandon them. Surprise: you will not necessarily drown if you go swimming after lunch.

A blatant example is the role of competition in evolution, which is treated by many as a scientifically established law of nature, and often taken for granted by economists and psychologists...at the same time that others argue that evolution, being a "theory" is no more than a "guess." Biology has been steadily giving increasing recognition to the importance of symbiosis in evolution, alongside competition, as well as diversification that by-passes competition, but "the survival of the fittest," a metaphor drawn by Darwin from the description of early industrial society by Herbert Spencer, survives as a binding metaphor for human behavior. [ Continue ]

Systematic Thinking About How We *Package* Our Worries

This seems to be a moment for some systematic thinking about how we package our worries.

Most people seem to respond only if they have the ability to visualize a danger and empathize with the victims. This suggests the need for:

A realistic time frame. Knowledgeable people expected an eventual collapse of the Shah's regime in Iran, but did nothing because there was no pending date. In contrast, many prepared for Y2K because the time frame was so specific.

A specific concern for those who will be harmed. If a danger lies beyond my lifetime, it may seem significant if it threatens my grandchildren. People empathize more easily with polar bears and whales than with honey bees and bats. They care more about natural disasters in countries they have visited. [ Continue ]

Making and Changing Minds

We do not so much change our minds about facts, although we necessarily correct and rearrange them in changing contexts. But we do change our minds about the significance of those facts.

I can remember, as a young woman, first grasping the danger of environmental destruction at a conference in 1968. The context was the intricate interconnection within all living systems, a concept that applied to ecosystems like forests and tide pools and equally well to human communities and to the planet as a whole, the sense of an extraordinary interweaving of life, beautiful and fragile, and threatened by human hubris. It was at that conference also that I first heard of the greenhouse effect, the mechanism that underlies global warming. A few years later, however, I heard of the Gaia Hypothesis (proposed by James Lovelock in 1970), which proposed that the same systemic interconnectivity gives the planet its resilience and a capacity for self correction that might survive human tampering. Some environmentalists welcomed the Gaia hypothesis, while others warned that it might lead to complacency in the face of real and present danger. With each passing year, our knowledge of how things are connected is enriched but the significance of these observations is still debated. [ Continue ]

To: George W. Bush

The White House

Dear Mr. President,

I hope that some of my colleagues will offer you a shopping list of specific goals. I want, however, to address a broader question that requires fitting together the findings of many researchers and that resonates with popular culture and the political process. For simplicity, let me put it in terms of a single question: Can human beings learn?

Most people would answer, of course. I am sure that you yourself remember learning things from time to time, at Yale for instance, and perhaps since. But I write to point out that we are steadily reducing our estimate of what and how much humans can learn, except at a relatively trivial level. And we are making policy on that basis.

We live at a time of impressive progress in biology (especially genetics and neuroscience), which has replaced physics as the most glamorous of the sciences. Certainly you have had to take positions on applications of this new science to human beings, but you may be unaware of the indirect influence of popularized scientific ideas on our systems of child care, education, health, and criminal justice. In all of these areas we are drifting toward biological determinism, but the situation is complicated by the popular belief that, whereas what human individuals can learn is limited, scientists can learn to tinker. Thus we regard more and more problems of individual behavior as biologically determined, but we are increasingly ready to treat them biochemically, and looking forward to treating them genetically. Our fatalism about the individual capacity to learn and heal is matched only by our technological hubris. [ Continue ]

"What Now?" (2001)

What Next? End Economic Sanctions

America has long been spared the most painful experience of modern warfare: massive civilian casualties. The terrorist attack on September 11 has taught us what most other nations learned earlier in the century, that no one is safe. Pearl Harbor was a military target and American civilians were safe in their homes and communities through two world wars. We have also been spared that other less dramatic experience of modern warfare, the destruction of infrastructure, with all the dislocation, privation and economic disruption that follow. In earlier wars, the U.S. infrastructure was ramped up, not destroyed, but today significant parts of it are at risk. The terrorist attack has newly taught us how dependent we are on a complex and interconnected infrastructure and the economy is reeling, but we have yet to understand the implications of these new experiences. [ Continue ]

"How can we build a new ethics of respect for life that goes beyond individual survival to include the necessity of death, the preservation of the environment, and our current and developing scientific knowledge?"