Spinoza had argued that our capacity for reason is what makes each of us a thing of inestimable worth, demonstrably deserving of dignity and compassion. That each individual is worthy of ethical consideration is itself a discoverable law of nature, obviating the appeal to divine revelation. An idea that had caused outrage when Spinoza first proposed it in the 17th century, adding fire to the denunciation of him as a godless immoralist, had found its way into the minds of men who set out to create a government the likes of which had never before been seen on this earth.

Spinoza's dream of making us susceptible to the voice of reason might seem hopelessly quixotic at this moment, with religion-infested politics on the march. But imagine how much more impossible a dream it would have seemed on that day 350 years ago. And imagine, too, how much even sorrier our sorry world would have been without it.

Introduction

History illuminates our origins and keeps us from reinventing the wheel. But the question arises: History of what? Do we want the center of culture to be based on a closed system, a process of text in/text out, and no empirical contact with the real world? One can only marvel at, for example, art critics who know nothing about visual perception; "social constructionist" literary critics uninterested in the human universals documented by anthropologists; opponents of genetically modified foods, additives, and pesticide residues who are ignorant of genetics and evolutionary biology.

In the seventeenth century, people not only believed in that constricted past but thought that history was near its end: The apocalypse was coming. A realization that time may well be endless leads us to a new view of the human species—as not being in any sense the culmination but perhaps a fairly early stage of the process of evolution. We arrive at this concept through detailed observation and analysis, through science-based thinking; it allows us to see life playing an ever greater role in the future of the universe.

There are encouraging signs that the third culture now includes scholars in the humanities who think the way scientists do. Like their colleagues in the sciences, they believe there is a real world and their job is to understand it and explain it. They test their ideas in terms of logical coherence, explanatory power, conformity with empirical facts. They do not defer to intellectual authorities: Anyone's ideas can be challenged, and understanding and knowledge accumulate through such challenges. They are not reducing the humanities to biological and physical principles, but they do believe that art, literature, history, politics—a whole panoply of humanist concerns—need to take the sciences into account.

As the Italian scholar Gloria Origgi, writes:

No matter what your attitude is towards science, no one in the humanities can ignore that something has changed in the way we think about a number of key oppositions such as: nature-nurture, rational-irrational, conscious-unconscious, individual-social, mind-body, digital-analogical, masculine-feminine, etc. To discuss such matters today, we have to overcome the Freudian-Lacanian-Foucaultian vulgata and take a look at what science has to tell us.

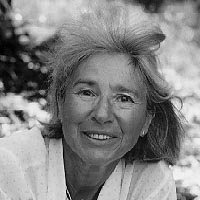

Enter Rebecca Newberger Goldstein, a novelist trained as a philosopher, who is one of the leading science-based humanities scholars: intellectually eclectic, seeking ideas from a variety of sources and adopting the ones that prove their worth, rather than working within "systems" or "schools." Goldstein knows science, and easily communicates with scientists. Her novels, and her studies of nonfiction studies of Gödel and Spinoza, are excellent examples of science-based thinking by an enlightened humanities scholar.

And now, Rebecca Goldstein on Spinoza and the voice of reason.

—JB