[Photo: Copyright © Julia Zimmerman]

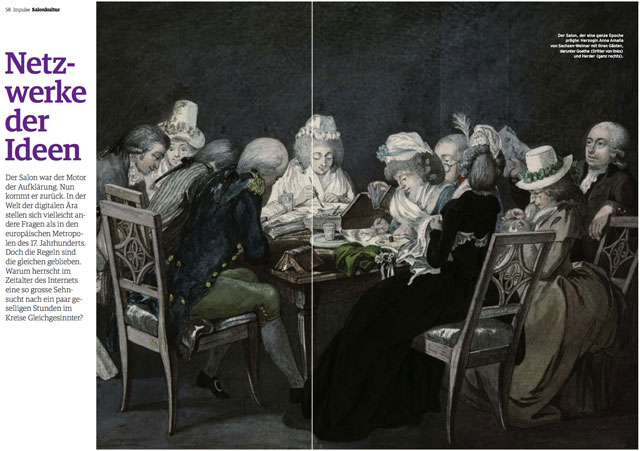

We are apparently now in a situation where modern technology is changing the way people behave, people talk, people react, people think, and people remember. And you encounter this not only in a theoretical way, but when you meet people, when suddenly people start forgetting things, when suddenly people depend on their gadgets, and other stuff, to remember certain things. This is the beginning, its just an experience. But if you think about it and you think about your own behavior, you suddenly realize that something fundamental is going on. There is one comment on Edge which I love, which is in Daniel Dennett's response to the 2007 annual question, in which he said that we have a population explosion of ideas, but not enough brains to cover them.

—Frank Schirrmacher, 2009

Frank Schirrmacher died on June 12th of a heart attack. He was the influential German journalist, essayist, best-selling author, and since 1994 co-publisher of one of the leading national German newspapers, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), where he was Editor of the Feuilleton, cultural and science pages of the paper. FAZ is a non-profit company based on a foundation mode. He was one of five "Herausgeber," literally translated "publisher," but in reality he was a mix of head of Feuilleton, co-editor in chief and CEO.

Schirrmacher's death is a loss that will be felt not just in Germany but throughout the world. He is irreplaceable. It's fair to say that he has no equivalent here in the United States. He was a beacon of light, a visionary thinker who initiated international conversations on the emerging questions that mattered, including the human genome, the third culture, the role of technology in a society. He will be greatly missed.

We were introduced in early 2000 by German media mogul and digital pioneer Hubert Burda, and began a conversation which lasted until the week of his death. In May of 2000, based on our several long telephone calls, Schirrmacher wrote a manifesto, a call-to arms, entitled "Wake-Up Call for Europe Tech," published in FAZ, which called for Europe to adopt the ideas of the third culture. His agenda: to change the culture of the newspaper and to begin a process of change in Germany and Europe. In the final paragraph he wrote:

"Over the next few months, to ensure we are informed slightly in advance, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung will be running a series of articles by the theoreticians of what John Brockman has dubbed the 'third culture'. Europe should be more than just a source for the software of ego crisis, loss of identity, despair, and Western melancholy. We should be helping write the code for tomorrow."

The manifesto, and Schirrmacher's publishing program, was a departure for FAZ which at that time had a somewhat conservative profile. It was widely covered in the German press and made waves in intellectual circles.

Within weeks following publication of his manifesto, Schirrmacher began publishing articles by notable third culture thinkers, began to provide extensive FAZ coverage of Edge features and events, and became an Edge contributor himself. On many occasions we published pieces simultaneously on Edge and in FAZ. In 2009, I interviewed him in his Frankfurt office, the result being the publication of "The Age of the Informavore: A Talk with Frank Schirrmacher." "The term informavore," Schirrmacher noted, "characterizes an organism that consumes information. It is meant to be a description of human behavior in modern information society, in comparison to omnivore, as a description of humans consuming food." Among the Edgies commenting on the piece in the ensuing Reality Club conversation were Daniel Kahneman, George Dyson, Jaron Lanier, Nick Bilton, Nicholas Carr, Douglas Rushkoff, Gerd Gigerenzer, John Perry Barlow, Steven Pinker, John Bargh, George Dyson, John Brockman, David Gelernter, and Evgeny Morozov.

Writing a few months later in Stuttgarter Zeitung, Gabor Paal took note of the effect of FAZ's sustained coverage of the third culture on German intellectual life. Researchers such as evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, anthropologist Gregory Bateson, mathematician Roger Penrose, biologist Lynn Margulis, geographer Jared Diamond, psychologist Steven Pinker ..."come from the 'exact' sciences, take care of basic questions of human existence. And they write about their work in thick books in which they—like 'real' humanists—take hundreds of pages to present their own thesis. Inspired by Brockman's thesis beginning in the late 1990s, the FAZ Feuilleton began to deal with developments in the natural sciences. At about the same time, Der Spiegel regularly began publishing "third culture" topics on the front page, and entices its readers with article on the origin of language, the end of the universe, or about Neurotheology."

It's now been fourteen years since publication of his manifesto, and the national conversation he began in Germany continues in the pages of FAZ, and has also been joined in a robust way by the Feuilleton of Süddeutsche Zeitung, the other of the two national newspapers in Germany.

As a tribute, Edge turns over its front page to remember Schirrmacher by presenting "Maybe He Was The Only True Futurist-Humanist," a piece organized by Schirrmacher's long-time colleague Jordan Mejias, FAZ's U.S. Cultural editor; an excerpt from the Süddeutsche Zeitung obituary "Man of The Future," co-authored by Andrian Kreye, editor of the SZ Feuilleton and Edge contributor; impressions in the German press regarding his involvement with third culture ideas in "FAZ Co-Editor Is Dead: Frank Schirrmacher Set The Central Issues Of Our Time," a piece by Peter von Becker, in Potsdamer Neueste Nachrichten; a re-publication of Schirrmacher's Edge feature "The Age of the Informavore"; Hubert Burda's obituary in his Focus Magazine, "Farewell to my friend Frank Schirrmacher"; and finally, the 2010 EDGE @ DLD panel, "Informavore," featuring a video of Schirrmacher, Andrian Kreye, David Gelernter, and myself.

Frank Schirrmacher & John Brockman, Munich, January 2010

At some point I plan to write more about Schirrmacher, the man, his agenda, and the intellectual inspiration he provided in the quest for a second enlightenment, one which would be built on the ideas of the third culture. But now is not that time. Now is a time for remembering.

—John Brockman

Frank Schirrmacher's Edge Bio Page

MAYBE HE WAS THE ONLY TRUE FUTURIST-HUMANIST

Literary agent John Brockman, Internet pioneer Jaron Lanier, science and technology historian George Dyson and computer scientist and artist David Gelernter remember Frank Schirrmacher. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (June 13, 2014) [MORE...]

FAREWELL TO MY FRIEND FRANK SCHIRRMACHER

by Hubert Burda

The editor of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Frank Schirrmacher, died at 54 years. Germany has lost a great thinker. Focus Magazine (June 17, 2014) [MORE...]

ON THE DEATH OF FRANK SCHIRRMACHER

MAN OF THE FUTURE

An Obituary by Gustav Seibt, Franziska Augstein and Andrian Kreye

... Not a traditional man of culture ... Schirrmacher had a large double talent: he could create new topics and get them out early. He knew—months before others knew it—what would be the language in the Federal Republic. And he was great in terms of the agreement with important people. He wrote his articles rather quickly. In addition, however, he wanted to get involved, to have his fingers everywhere. He succeeded in both. Süddeutsche Zeitung (June 12, 2014) [MORE...]

FAZ CO-EDITOR IS DEAD

Frank Schirrmacher Set The Central Issues Of Our Time by Peter von Becker

What is happening today in the Internet or in the biotech laboratories, raises pressing legal and moral questions. Frank Schirrmacher had the intellectual antenna and the fire of passionate journalist. Potsdamer Neueste Nachrichten (June 13, 2014) [MORE...]

THE AGE OF THE INFORMAVORE

A Talk With Frank Schirrmacher

We are apparently now in a situation where modern technology is changing the way people behave, people talk, people react, people think, and people remember. And you encounter this not only in a theoretical way, but when you meet people, when suddenly people start forgetting things, when suddenly people depend on their gadgets, and other stuff, to remember certain things. This is the beginning, its just an experience. But if you think about it and you think about your own behavior, you suddenly realize that something fundamental is going on. Edge (October 25, 2009) [MORE...]

Edge & DLD: INFORMAVORE

In 2010, Edge was in Munich for DLD 2010 and an Edge & DLD event. The event, entitled "Informavore," is a discussion featuring Frank Schirrmacher, Editor of the Feuilleton and Co-Publisher of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Andrian Kreye, Feuilleton Editor of Sueddeutsche Zeitung, Munich; and Yale computer science visionary David Gelernter, who, in his 1991 book Mirror Worlds presented what's now called "cloud computing." [MORE...]